'Strongman' image may not win votes for Narendra Modi

- Published

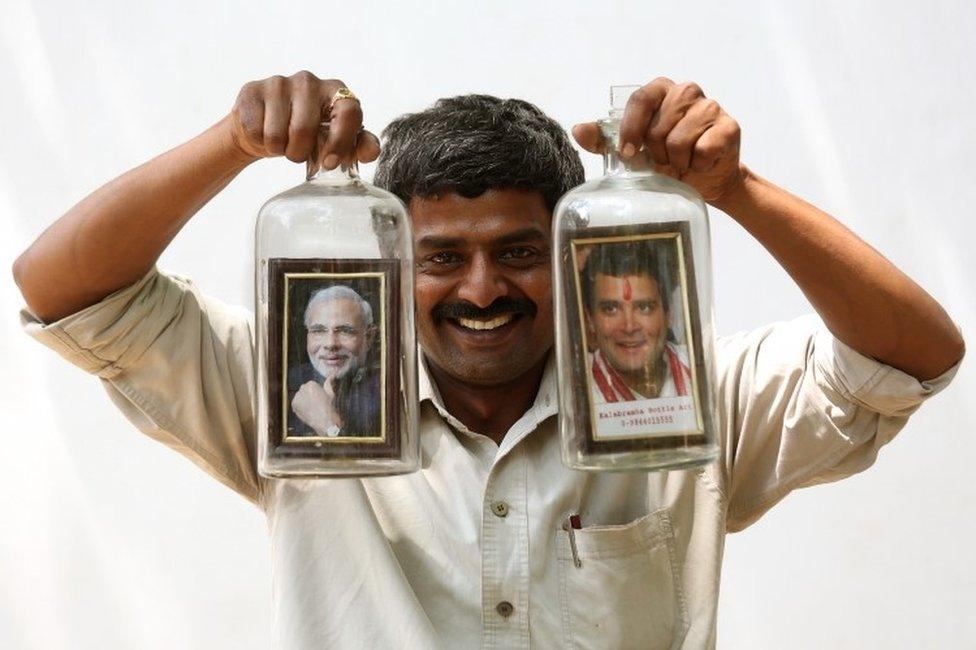

India's elections are keenly contested

Good intentions are ubiquitous in politics, wrote American economist Bryan Caplan. What is scarce, however, are "accurate beliefs". Elections are always a good occasion to test such beliefs.

Is India's Narendra Modi really a strongman leader in the mould of Turkey's President Recep Tayyib Erdogan and Russia's leader Vladimir Putin? Will he succeed in making the mammoth 2019 election a presidential referendum on his performance?

Are people really unhappy that Mr Modi did not carry out the kind of radical economic reforms that many thought he would? Is he a clear favourite to secure a second term in power, thanks to the lack of a charismatic rival? Is good economics bad politics in the world's largest democracy? Does rising nationalism threaten democracy?

In his engaging new book, Democracy On The Road, Ruchir Sharma grapples with these questions and more. The global investor, author and New York Times columnist has made 27 election trips to India since 1998 during which, he says, he must have "driven a distance nearly equal to a lap around Earth". He's been to more than half of India's 29 states and to the 10 most populous and politically important states more than once. I caught up with him on his recent trip to India.

Many compare Modi with Erdogan and Putin

Opinion polls in India have sometimes shown a public desire for a strong leader, unshackled from the compulsions of parliamentary democracy. However, Mr Sharma says, the electoral realities of India actually "rebel" against strongman leaders.

"In the end, Indians root for the underdog," he told me. "The democratic impulse is strong. If the leader becomes arrogant, he is pulled down by the people. Most importantly, it is difficult for one leader to dominate for long in this extraordinarily diverse country."

So diverse that a leading multinational firm divides 29 Indian states into a further 14 sub-regions because "consumer tastes, habits and languages are far more fragmented in India". The real strength of Indian democracy, says Mr Sharma, lies in its diversity.

He believes in spite of Mr Modi projecting himself as a strongman, India is "really no country for strongmen".

"The 2019 election is being cast as a contest between Modi and the rest, a referendum on India's appetite for strongman rule and commitment to democracy. More likely, the election will shape up as a series of state contests. The result will depend on whether the opposition parties can work together to unseat the BJP."

There is ample evidence to support Mr Sharma's claim. Regional parties now hold more than 160 seats - nearly a third of the seats - in parliament, up from 35 in the early phase after Independence. "This important new phenomenon has converted our general elections into a combination of state-level regional or sub-national elections," says psephologist Prannoy Roy.

BJP's historic win in 2014, many believe, was a "black swan" - a highly unlikely and unpredictable event. Mr Sharma says "BJP could win a third of the popular vote as it did during the Modi wave in 2014, yet lose its majority of seats in the parliament".

One reason, according to Mr Sharma, is "incumbents don't usually win, and challengers do".

Winning parties in crowded state elections often need only a third of the vote to take a majority of seats. Prannoy Roy found that 70% of the governments in big and medium-sized states were thrown out by voters between 1977 and 2002. The picture now, he believes, is more mixed: governments today have a "50:50" chance of being re-elected.

Indian political power is "hard won and fleeting" - candidates have to go through tests of community, family, inflation, welfare, development, corruption. Between 10-20% of the electorate are made up of some of the dominant communities. Most states are "hotbeds of anti-incumbency".

Some 900 million people are eligible to vote in the ongoing elections

Mr Sharma also doubts whether most Indians are really unhappy that Mr Modi did not turn out to be the reformer they may have hoped for.

"India's political DNA," he says, "is fundamentally socialist and statist". "There is no real support for systematic free-market reform, either among voters or among the political elite, and no sign that what is generally considered good economics will ever become a consistent election-winning strategy." Reforms in India, usually, have been either by stealth or triggered by an economic crisis.

Also, Mr Sharma believes that fears of rising nationalism and religious politics putting democracy in peril are unfounded.

They tend to "underestimate the check provided by sub national pride". Returning to his favourite theme, he says India is too "heterogeneous to be dominated by populist nationalism". And, in the end, he believes the 2019 ballot will "offer a choice of two different political visions, one celebrating the reality of many Indias, the other aspiring to build one India".

Read more from Soutik Biswas

Follow Soutik at @soutikBBC, external