India election 2019: Meeting a 'foot soldier' of the Hindu far-right

- Published

Sharad Sharma is a functionary of a radical Hindu group

Ever since Narendra Modi swept to power in 2014, India has seen a resurgence in right-wing Hindu nationalism. The Indian PM has made it the cornerstone of his ongoing re-election campaign. Soutik Biswas meets a self-proclaimed foot soldier of Hindu nationalism, and explores the forces driving the rise of the far-right in India.

Sharad Sharma was 20 when right-wing Hindu mobs tore down a mosque in his city, triggering one of the worst bouts of religious riots in independent India.

It happened in the fabled city of Ayodhya in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh on 6 December, 1992.

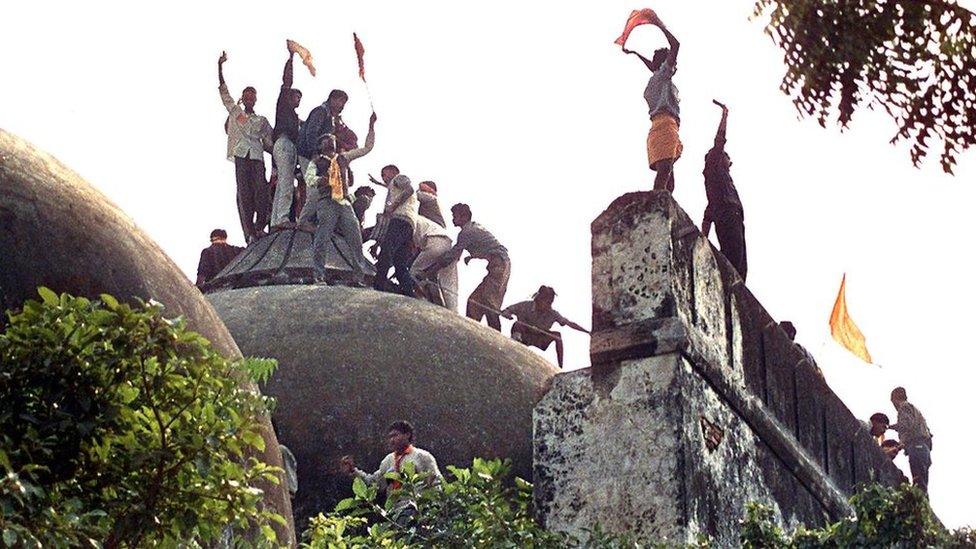

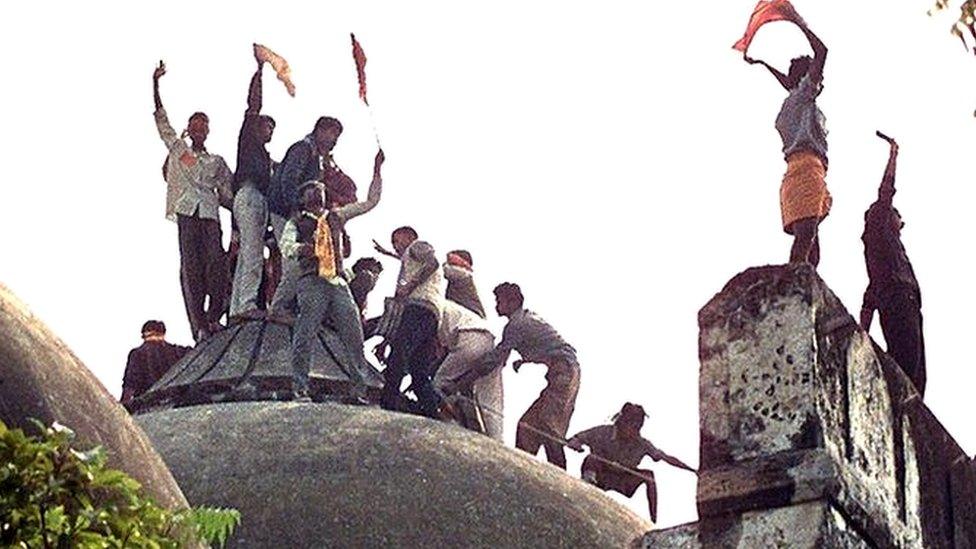

The mob that razed the 16th Century Babri mosque claimed that it was built on the site of a temple destroyed by Muslim rulers. More importantly, they said it was standing on ground believed to be the birthplace of the Hindu god, Rama.

On that fateful Sunday evening, news about the fallen mosque swept the city. Young men carrying saffron flags stood on its broken dome. As dusk fell, a journalist at the site reported, a "red cloud of dust settled on the rubble" and all that remained was the "myth of Hindu tolerance"., external The riots that followed the demolition killed nearly 2,000 people across India.

"I was not at the site. I remember people running through the town, returning from the site. They were jubilant, shouting Jai Sri Ram [hail lord Ram]," Mr Sharma told me when I met him in Ayodhya recently.

He had grown up in the temple-studded city listening to stories of the internecine dispute. Hindus and Muslims have been at loggerheads over the shrine for more than a century.

Right-wing Hindu mobs razed the 16th Century mosque in 1992

Earlier that year, he had joined the Bajrang Dal, a far-right Hindu supremacist group that was mobilising support to build a Hindu temple at the site of the destroyed Babri mosque. The group is part of the "Sangh Parivar" or family of Hindu nationalist groups. They are led by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), widely regarded as the parent organisation of Narendra Modi's governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bajrang Dal is officially described as a "security ring of Hindu society".

But the group has been accused of burning alive an Australian missionary and his two children, external and attacking churches, rioting and forcibly converting Muslims, external. American political scientist Paul Brass wrote that it resembled a "fighting protection squad for the other [Hindu nationalist] organisations, a somewhat pathetic, but nevertheless dangerous version of the Nazi SA".

India votes 2019

"At Bajrang Dal, I would hold meetings with officials, and do some organising work. That's all," Mr Sharma says.

Four years later - in 1996 - he joined the Vishwa Hindu Parisad (VHP), or the World Hindu Council, which was at the forefront of the demolition of the mosque. Political scientist Manjari Katju describes the group as a "clamorous and militant sibling" of the RSS.

Two years later, Mr Sharma was given the responsibility of handling the media and appointed the local spokesperson of the organisation. With time, media interest in the temple appears to have waned. These days, he says, he mostly interacts with a handful of local journalists.

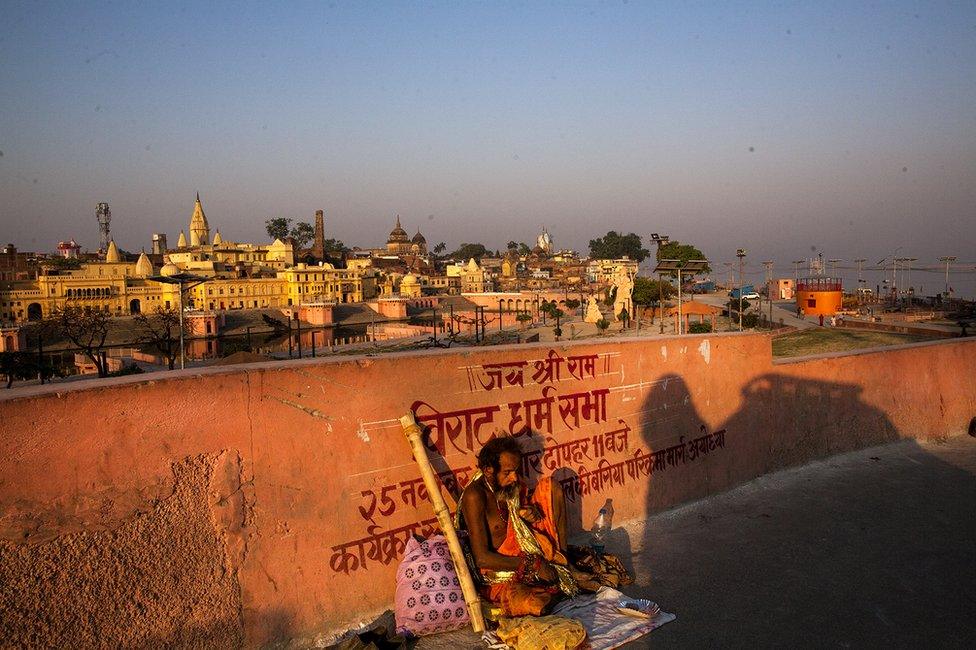

Ayodhya is a city of 50,000 people with more than 100 temples

"Agitating for the temple is not all we do. We run schools, dispensaries, work with tribespeople all over the country. There's a lot of other work."

The evolution of the son of a lawyer and a school teacher into a member of a far-right supremacist group was perhaps foretold.

In his early years, Mr Sharma spent a lot of his time travelling with his father, who practised as a criminal lawyer, and wrote articles in newspapers. His grandfather studied engineering in Lahore (now in Pakistan), and worked as a civil engineer in Ayodhya.

When he was a student, Mr Sharma would often attend local shakhas or daily meetings held by the RSS. There they were taught lessons on "nationalism, social science, moral science and history". One recent evening, on the banks of Sarayu river which flows past Ayodhya, I saw a group of children holding hands, chanting poems and reciting lessons.

"They are children of a shakha. That's how we learnt things here," Mr Sharma says.

Ayodhya has been a flashpoint since the demolition sparked riots

As a teenager, he lived in a city that was rapidly slipping into the politics of grievance, frustration and discrimination.

In 1989, radical Hindu religionists unveiled plans to build a "grand Ram temple" where the Babri mosque stood. A coalition of Muslim groups responded with protest marches and rallies. A senior BJP leader launched a nationwide march to the temple. It was, as observers said - a "full blown campaign of hatred by communalists on both sides".

The same year, Hindu groups raised an appeal to collect bricks embossed with the name Ram and small donations from tens of thousands of villages across India. The bricks would be consecrated and taken to Ayodhya. Firebrand religious leaders and kar sevaks (Hindu volunteers) streamed into Ayodhya to canvass support for the temple.

Myths swirled around the disputed site. In VHP's telling of history, 176,000 Hindus were killed trying to defend the temple upon which India's first Mughal ruler Babur allegedly built the mosque. "The death figure is absurd and has no basis whatsoever, but to its credit VHP has turned puerile propaganda into popular history," says Valay Singh, author of Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord.

Mr Sharma says Hindus can never provoke violence

Mr Sharma remembers it all as a "very heady time".

"I was, at once, both inspired and angry when I heard the speeches of the saints and the stories about the mosque. I felt that a historical wrong had to be corrected. We would be on the roads offering food and water to the volunteers who began arriving here from all over India."

Things came to a head in 1990 when the police fired on kar sevaks near the city for defying a curfew and shoot-on-sight orders, killing several of them.

"That was really the last straw for us," he says. "I was shocked that innocent believers had been killed.

"Bringing down the mosque two years later was a reaction to the killing of our volunteers."

In person, Mr Sharma, a masters graduate in Hindi, is unfailingly polite and low-key. His wife is a homemaker who also does social work, and his son is studying to become a lawyer in the bustling state capital of Lucknow, some 135km (83 miles) from Ayodhya. His brother runs a car rental firm. He says he has a few Muslims friends, who "also want the temple to be built".

Mr Sharma is a self-professed news junkie, saying his favourite hobby is "discussing the news of the day with fellow workers and journalists".

His Twitter feed is more forceful than the man himself: he rails against "anti-nationals" and says the election is a "fight between nationalists and anti-nationals", a signature riff of Mr Modi's campaign. In his WhatsApp profile picture, he smilingly poses with the powerful BJP president Amit Shah.

VHP led the movement for the Ram temple to be built in Ayodhya

The fact that Mr Sharma isn't a star of the resurgent Hindu right doesn't seem to bother him. He's happy to remain a "committed foot soldier" and wait patiently for the temple to be built. A few doors away from his workplace, some 350,000 donated bricks bearing the name Ram and carved sandstone pillars are heaped in a "workshop". All this will be used to build the temple.

I ask him whether he feels frustrated that the temple hasn't yet been built. The dispute over the site has been fought in India's courts for more than half a century and a solution doesn't appear to be in sight yet.

"India fought the British for nearly 100 years to become independent. The Babri mosque came down just 26 years ago. It marked the end of our religious slavery. The temple will be built. We will wait. The people are with us.

"Who knows? Maybe another generation will build the temple."

More than 350,000 bricks embossed with the name of Ram are stored in a workshop

What about the lives lost in rioting and violence over the temple and the allegations that it was mostly provoked by VHP storm troopers?

"If attacks have happened in the past, it is because historical wrongs had to be corrected. After correcting these wrongs, we can all live together."

Mr Sharma denies that the VHP has been involved in stoking riots against minorities.

"Hindus can never be rioters. There's no Hindu terror. We never start a confrontation. If our temples are attacked or cows slaughtered, we will react and resist. If we are heavy in number, we will punish the enemy," he says.

"We are humans. Things happen."

Read more from Soutik Biswas

Follow Soutik on Twitter at @soutikBBC, external

- Published6 December 2017

- Published24 April 2019

- Published15 October 2015