India elections 2019: The taming of the great Indian election

- Published

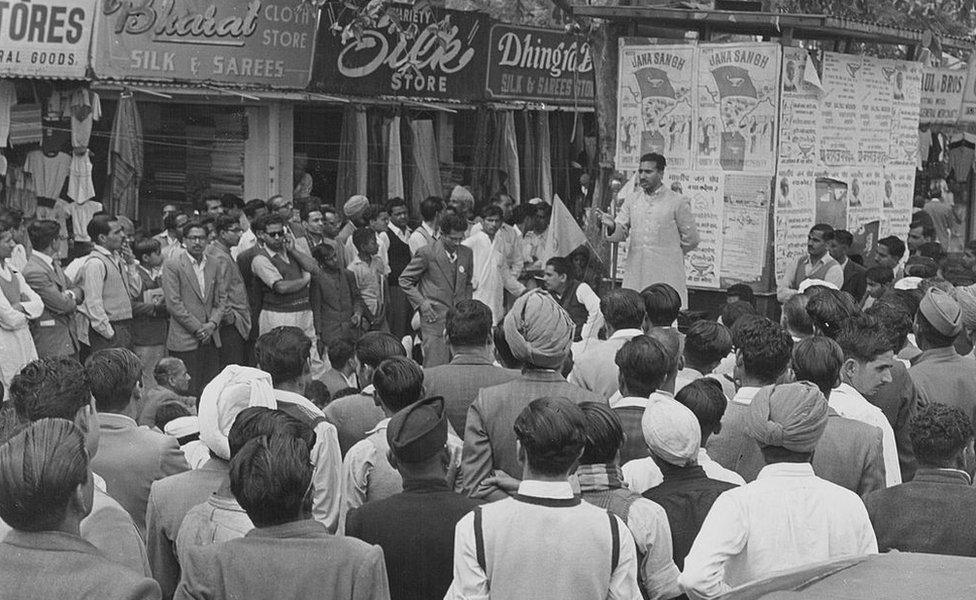

Campaigning for Indian elections has changed drastically over the years

Indian elections have long been billed as a colourful and raucous exercise in democracy. But that has changed over the years because of stricter campaign rules and spending limits, says Shivam Vij.

Amid the beating of drums and shouting of slogans, hundreds of thousands of people, wearing saffron caps, cheered Prime Minister Narendra Modi as his convoy travelled seven kilometres in two hours for his road show. They wore "Modi forever" t-shirts and showered rose petals on him.

Mr Modi was on his way to file his nomination in Varanasi in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, seeking to become the ancient city's representative in parliament for a second time.

But an opposition leader promptly complained to the poll watchdog - the Election Commission of India - alleging that the road show had exceeded the amount of money candidates are allowed to spend on their entire campaign. That limit is seven million rupees ($100,000; £77,500).

Mr Modi's road show alone, allegedly cost more than what he is allowed to spend on his entire campaign

The tightening noose

"The big festival" or the "festival of democracy" is how the Election Commission is describing India's ongoing general election, the country's 17th since independence. But it's an old cliche because the so-called festive election is no longer quite so festive.

With every election, the Election Commission has become stricter about how much money individual candidates spend on their campaigns.

The noose has tightened so much that even if you were to look for it, you will rarely find any street-level campaigning now. The posters, wall paintings, flags and buntings, loudspeakers blaring music, and the noisy processions have all but disappeared.

In 2010, then Chief Election Commissioner, SY Quraishi, created a new department to monitor expenditure and framed new rules. Since then, candidates have had to inform the commission in advance about how they will spend their money - and they have to be meticulous. How many vehicles will they use for campaigning? How many public meetings are being organised? How many posters and banners are being put up?

SY Quraishi is credited with changing the rules of the game

Writing on walls is not allowed any more because that would be defacement of public or private property; and the use of plastic buntings is discouraged because the environment matters.

"Flying squads," "static surveillance teams" and "video surveillance teams" now go around each constituency in a cat and mouse chase, taking down unauthorised posters and recording expenses that were not approved in "shadow registers".

Rates for every kind of expense are fixed (six rupees to rent a plastic chair or 100 rupees per plate for a meal). There's even a team to investigate if a newspaper article is in fact "paid news"- basically an advertisement masquerading as news - and the expense is added to the candidate's account.

Empty account books

This is a noble effort to make sure the election is a level playing field, and wealthier candidates don't have an undue advantage. But seven million rupees is also too little money to campaign before 1.65 million voters - that's the average population of a parliamentary constituency in India.

India votes 2019

To put this into perspective, consider this: It costs five rupees to send a letter by post to each voter in a constituency - that alone could cost more than eight million rupees overall.

The expenditure limit was raised in 2014 and has since not even been adjusted for inflation. No-one can make a case to increase the limit because most candidates claim to have spent far less than seven million rupees.

So many show artificially low figures fearing that the Election Commission will add expenses that it observed independently. In truth, it would be rare for a candidate to win a parliamentary seat without having spent several times over the official limit.

Smaller, street-level campaigns have all but disappeared

As a result, all that candidates need to do, is hide their expenses from the Commission's monitoring teams.

Should the Commission estimate that a candidate exceeded the limit, he or she could be disqualified even after winning the election at any point during their five-year term. Rarely has anyone been disqualified, but it has happened and the fear hangs like a sword over candidates.

Underground campaign

The result of this is that street-level campaigning - once so visible - has gone underground. Candidates are widely known to distribute cash and free alcohol, often in the dead of the night, in exchange for votes - although research suggests that bribes don't actually win votes.

Officials have been catching and confiscating ever larger amounts of illicit cash and alcohol - they have seized more than $470m worth of cash, alcohol, drugs and gold in connection with the election, external since 26 March, according to the Election Commission's data.

Even if officials occasionally turn a blind eye or miss something, the candidate's opponents may still file an official complaint. And then there's the media. So contestants take no chances and instead find ways to try and get around the spending limit.

For example, if a candidate intends to use five cars to campaign, she would be given as many stickers that authorise each vehicle for campaign purposes. If a vehicle that was not authorised is used, officials could impound it.

In practice, candidates use many more vehicles but without the party flag adorning the bonnets. That's how they can claim that the vehicle was not used for campaigning. So money is still being spent on the vehicle but it now looks like any other vehicle on the road, robbing the election of its sound and colour.

Political parties now need to account for virtually every poster and bunting

Mr Quraishi, who enacted many of these rules, counters that the real festival is in the voter turnout, which has been rising. "It has gone up from 35% back in the day to around 70% these days. Who says the festival is dead? It's just a more disciplined one and many voters have appreciated that candidates don't deface the facades of their homes anymore."

Individuals over masses

To be sure, campaign finance regulations are not the only reason the colour has gone out of elections in India. Like elsewhere in the world, technology is also responsible. With the increasing penetration of cable TV and smartphones with cheap data, campaigning is targeting individuals over masses.

Digital marketing agencies are thriving, bringing ruin to companies that specialise in making election merchandise.

It helps that spending on micro-targeting is easier to hide from the Election Commission's ever vigilant eyes. Digital spends are tough to track and avoid the hassle of having to take prior permission, which slows down the campaign.

Mr Quraishi says the "real festival" is the increasing voter turnout

Targeting voters individually also seems to have a better return on investment for candidates. Simon Chauchard, a political scientist at Columbia University in New York, has spent time asking Indian politicians how they spend their money to win votes. "Most candidates also invest in more individualised strategies online - for instance, local WhatsApp networks - but also offline," he says.

"There is now a sense that one cannot just drop by in a helicopter and give a speech. One needs to canvass, meet voters in person and at least pretend to listen to them."

Ironically, while individual candidates are so limited, there is no limit on the amount of money that political parties can spend on the campaign, defeating the purpose of ensuring a level playing field. Parties refuse to even entertain the idea of such curbs.

This financial asymmetry has ended up making Indian elections more presidential. While top leaders like Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi address mammoth rallies across India, the campaign has all but disappeared from street corners.

- Published22 May 2018

- Published19 April 2019