The bullying that led this doctor to take her own life

- Published

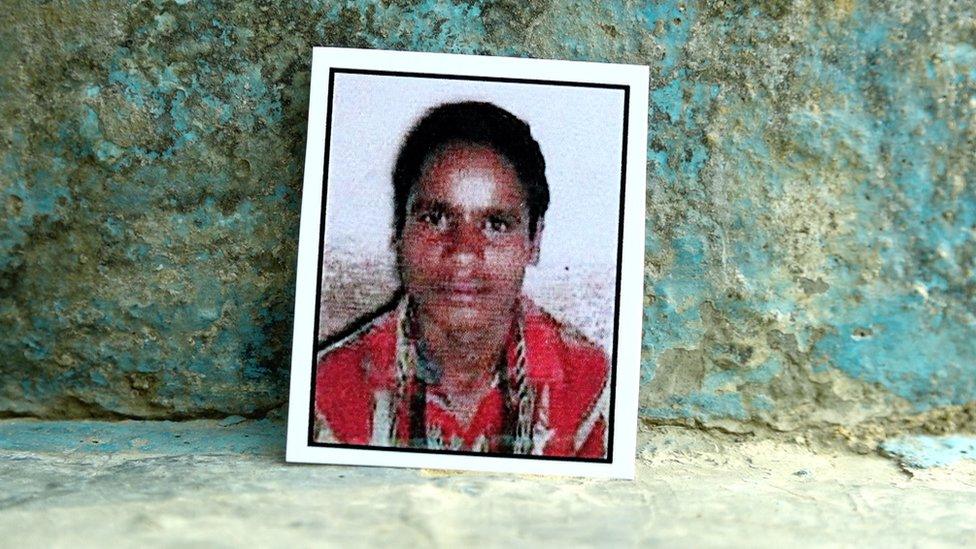

Payal Tadvi was harassed and bullied, her mother says

Three doctors have been arrested in India's Mumbai city amid allegations that their bullying of a young female colleague led her to take her own life. BBC Marathi's Janhavee Moole and Pravin Thakre report.

"I used to say I am Dr Payal's mother. But what do I say now?" Abeda Tadvi asks tearfully.

Her 26-year-old daughter, Payal, took her own life on 22 May after months of alleged harassment over her caste - she belonged to a Scheduled Tribe, a status given to historically disadvantaged tribes.

Payal's family has accused three of her seniors at the medical college - all women - of bullying her in the months leading up to her death.

Police arrested the three accused women on Tuesday and are investigating the matter, deputy commissioner of police, Abhinash Kumar, told the BBC. But they have denied the allegations in a statement published by the ANI news agency, saying they were being "unjustly" accused and demanded a "fair probe" and "justice".

Prior to the arrests, Nair hospital, where the women worked, had suspended them. The college had also launched an inquiry into the allegations.

Payal's death has shocked her colleagues and friends, who have been protesting in front of the hospital and demanding justice on her behalf. And it has shown the persistence of caste discrimination in an unlikely place - a college in Mumbai, India's financial hub and arguably its most urbanised city.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Payal was from Jalgaon in northern Maharashtra, the state where Mumbai is located. She married Salman Tadvi, who is a doctor in Mumbai, and moved to the city for a postgraduate medical degree.

She was studying to be a gynaecologist at Topiwala Medical College when she died. She had always wanted to be a doctor, her mother, Abeda, says. Her dream was to provide better healthcare for poor tribespeople.

She belonged to the Tadvi Bhil tribe, one of more than 700 Scheduled Tribes in India. Members of these tribes - who number around eight million, according to the last census in 2011 - are given "reservations" or quotas to rectify the wrongs of India's enduring caste hierarchies.

Payal was admitted to the college under the quota for Scheduled Tribes. Abeda says she was so proud of her daughter who had achieved so much despite their caste status and how poor they were.

"They taunted her for every small thing"

Abeda says that Payal had told her about the harassment she was facing from three of her seniors.

"She said they taunted her in front of patients for every small thing. They insulted her with slurs, threw files at her face. She said they did not even allow her to eat her meals in peace."

They also allegedly threatened to prevent her from practising medicine.

Payal (L) with her mother, Abeda

Abeda, who is being treated for cancer, would often visit Nair hospital, where Payal studied and practised because it is affiliated to her college.

She said she could rarely spend time with her daughter because she was always busy - so Abeda observed her from a distance.

"I saw the way she was being treated and decided to complain, but Payal stopped me," she said.

Payal feared that such a complaint would hurt the careers of the three women - and that they would end up harassing her even more.

But in December 2018, Abeda and Salman finally spoke to other seniors and professors about the harassment Payal said she was facing.

They demanded that Payal be allowed to work with a different team. She was reassigned, Abeda says, and she appeared a little relieved after that.

But, according to Abeda, the harassment soon resumed and around 10-12 May, Abeda herself filed a written complaint. "But this time they didn't take it seriously," she alleges.

Ten days later, Payal took her own life.

'It's sad and tragic'

Her death has raised the alarm on the widespread prevalence of bullying in schools and colleges across India. "Ragging", as it is euphemistically known, is banned but it continues. And students from lower castes often face the brunt of it.

Nair hospital has set up a committee to inquire into the allegations and it is expected to submit a report soon, Dr Ramesh Bharmal, dean of Topiwala college, told the BBC.

"It's sad and tragic. We are extremely shocked. How does this happen? What could we have done and what should we do now? All this could have been prevented," he adds.

Salman says that he met Dr Bharmal, who asked him why no-one had approached the dean's office. Salman told him that they had talked to staff in Payal's department and that they had followed the procedure.

"Why didn't they do anything?" he asks.

Abeda has the same questions: "What else were we supposed to do? Don't they know what is happening in their college? This was happening in front of their eyes. They should have looked into it."

Dr Barmal says that the college and hospital do have a system to address complaints of harassment - this includes counselling for new students, a committee to investigate complaints and random checks by supervisors.

"I was not aware. Otherwise this would not have happened. Proper measures could be taken and this...could be avoided," he adds.

'She was my backbone'

At the house in Jalgaon, where Payal grew up, relatives and neighbours are all in mourning. And they are eager to speak of Payal. They remember her as intelligent, ambitious and hard working.

They said she was inspired to become a doctor because her younger brother was born with a physical disability that prevented him from walking; and that she always wanted to help people.

Read more stories about Indian society

Abeda says what happened to Payal has made her wonder about other students from lower castes who are also pursuing a better future.

She thinks of her nieces and nephews, and other children from her tribe.

"Their parents now come to me and ask if they should ask their children to sit at home because they do not trust institutions to take care of them," Abeda says.

"She was my backbone. She was a backbone for the whole community. She would have been the first female doctor from our tribe. But that dream will now remain unfulfilled."

Information and advice

If you or someone you know is struggling with issues raised by this story, find support through BBC Action Line .

- Published20 May 2019

- Published13 January 2018