How Britain tried to 'erase' India's third gender

- Published

British judges described eunuchs as cross-dressers, beggars and unnatural prostitutes

In August 1852, a eunuch called Bhoorah was found brutally murdered in northern India's Mainpuri district.

She lived in what was then the North-West Provinces with two disciples and a male lover, performing and accepting gifts at "auspicious occasions" like births of children and at weddings and in public. She had left her lover for another man before she was killed. British judges were convinced that her former lover had killed her in a fit of rage.

During the trial they described eunuchs as cross-dressers, beggars and unnatural prostitutes.

'Moral panic'

One judge said the community was an "opprobrium upon colonial rule". Another claimed that their existence was a "reproach" to the British government.

The reaction was strange considering that a eunuch was the victim of the crime. The killing, according to historian Jessica Hinchy, curiously triggered British "moral panic about eunuchs" or hijras as they are called in South Asia.

"She was a victim of the crime but her death was interpreted as evidence of criminality and immorality of the eunuchs," Dr Hinchy told me.

Eunuchs describe themselves as being castrated or born that way

British officials began considering eunuchs "ungovernable". Commentators said they evoked images of "filth, disease, contagion and contamination". They were portrayed as people who were "addicted to sex with men". Colonial officials said they were not only a danger to "public morals", but also a "threat to colonial political authority".

For nearly a decade, Dr Hinchy, now assistant professor of history at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University, trawled the colonial archives on eunuchs that provided unusually detailed insights into the impact of colonial laws on marginalised Indians. The result is Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India, arguably the first in-depth history of eunuchs in colonial India.

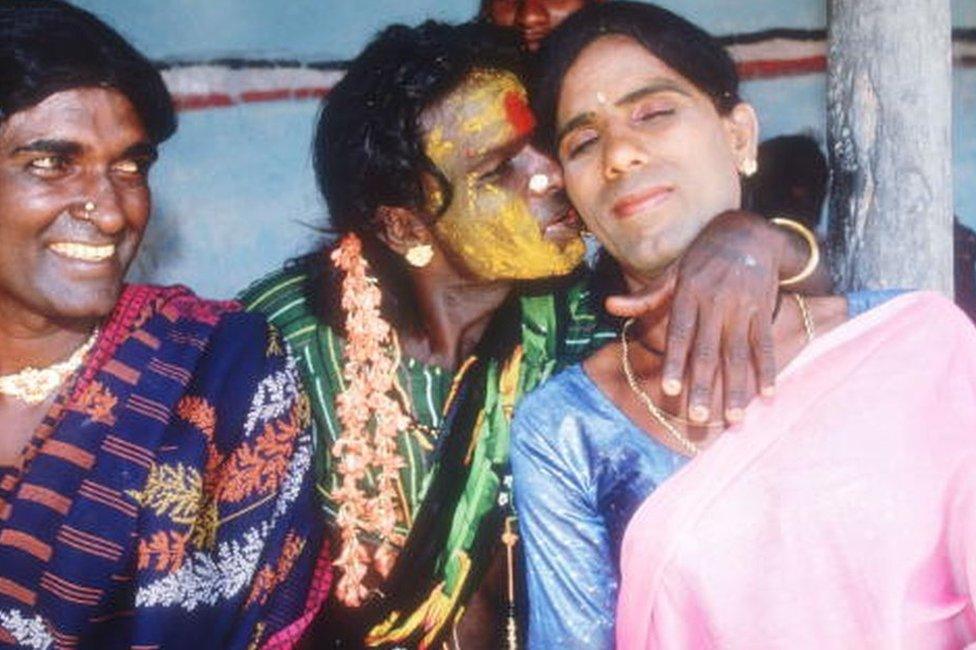

Eunuchs often dress up like women and describe themselves as being castrated or born that way. A disciple-based community, it has important roles in many cultures - from sexless people guarding harems to singing and dancing entertainers.

In cultures in South Asia, they are thought to have the power to bless or curse fertility. They live with adopted children and male partners. Today, many consider eunuchs transgender, although the term also includes intersex people. In 2014, India's Supreme Court officially recognised a third gender - and eunuchs (or hijras) are seen as falling into this category.

Eunuchs have important roles in many cultures

Bhoorah was among the 2,500 recorded eunuchs who lived in the North-West Provinces - now India's most populous state Uttar Pradesh and neighbouring Uttarakhand.

Years after her murder, the provinces launched a campaign to reduce the number of eunuchs with the objective of gradually causing their "extinction". They were considered a "criminal tribe" under a controversial 1871 law which targeted caste groups considered to be hereditary criminals.

The law armed the police with power of increased surveillance of the community. Police compiled registers of eunuchs with their personal details, often defining "an eunuch as a criminal and sexually deviant person". "Registration was a means of surveillance and also a way to ensure that castration was stamped out and the hijra population was not reproduced," says Dr Hinchy.

The BBC's Yogita Limaye reports from one celebration by activists and transgender people

Eunuchs were not allowed to wear female clothing and jewellery or perform in public and were threatened with fines or thrown into prison if they did not comply. Police would even cut off their long hair and strip them if they wore female clothing and ornaments. They "experienced police intimidation and coercion, though the patterns of police violence are unclear", says Dr Hinchy.

The community reacted by petitioning for the right to dance and play in public, and perform at fairs. The petitions, says Dr Hinchy, point to the economic devastation caused by the ban on dances and performances. In the mid-1870s, the eunuchs of Ghazipur district complained that they were starving.

Eunuchs have a visible presence in India

One of the most shocking moves of the authorities was to take away children who were living with eunuchs to "rescue them from a life of infamy". If eunuchs were living with a male child, they risked fines and jail.

Many of these children were actually disciples. Others appeared to have been orphans, adopted or enslaved as children. There were also children of musicians who performed with eunuchs and appeared to have lived alongside them with their families. Some eunuchs even lived with widows who had children. British officials saw the children as "agents of contagion and a source of moral danger".

"Colonial anxieties about the threat that hijras posed to Indian boys overstated the actual number of children residing with the community," says Dr Hinchy. According to records, there were between 90 and 100 male children found living with registered eunuchs between 1860 and 1880. Very few of them had been emasculated and most of them were living with their biological parents.

"The short-term aim of the law included cultural elimination of the eunuchs through erasure of their public presence. The explicit, long-term ambition was limiting, and thus finally extinguishing, the number of eunuchs," says Dr Hinchy. "To many high-ranking colonial officials, the small eunuch community endangered the imperial enterprise and colonial authority."

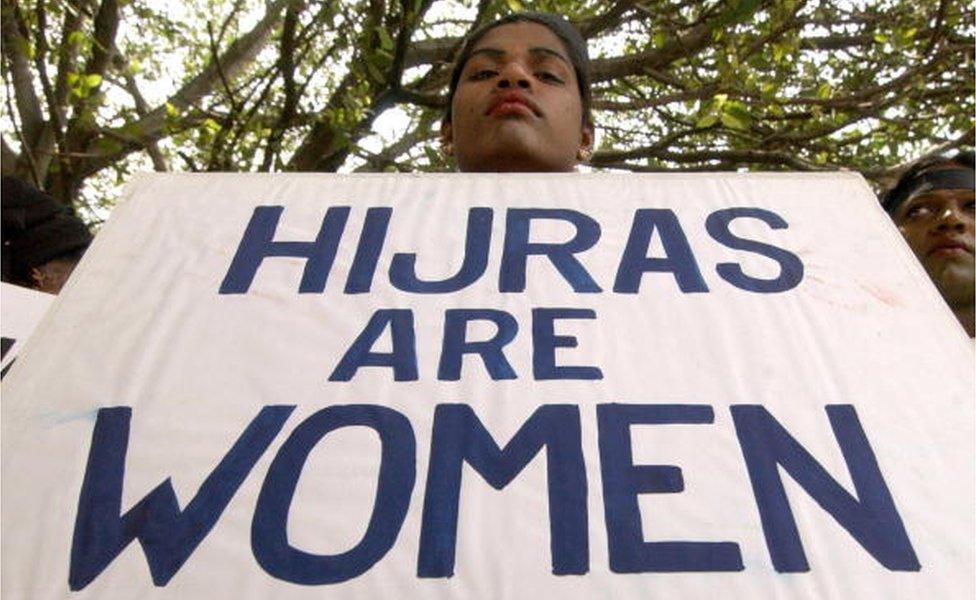

India recognised transgender people as a third gender in 2014

The British also began policing other groups which didn't fit the binary gender categories - effeminate men who wore female clothing, performed in public and lived in kin-based households, men who performed female roles in theatre and male devotees who dressed as women. "The law," says Dr Hinchy, "was used to police a diverse range of gender non-confirming people."

In many ways, the attitudes of the British and the English-speaking Indian elites to eunuchs echo aspects of Hindu faith that colonial rulers found abhorrent.

Indologist Wendy Doniger has written about the British rejection of the sensual strains of Hinduism as filthy paganism. However, religion was not a factor in the colonial rejection of eunuchs - it was more about "contamination", "filth", their sexual practices and public presence.

Yet, despite this dark history, eunuchs survived these attempts to eliminate them by evading the police, continuing to have a visible public presence and devising survival strategies. Dr Hinchy writes that they became skilful at law breaking, evading the police and keeping on the move. They also kept their cultural practices alive within their communities and in private places, which was not illegal. They also became adept at hiding property, so that police could not register it.

Their success is clear by the fact that despite being often defined as deviant and disorderly, Dr Hinchy says eunuchs "remain a visible presence in public space, public culture, activism and politics in South Asia".

In India, they continue to make a living by dancing at weddings and other ceremonies despite facing discrimination and living on the margins. Theirs is a stirring story of resilience and survival.

Read more from Soutik Biswas

- Published7 January 2019

- Published15 April 2014

- Published20 November 2018