Five murders, six men and 16 years of stolen lives

- Published

The Shinde brothers belong to a nomadic community

In March, India's Supreme Court overturned its own verdict, clearing six men of murder. The BBC's Soutik Biswas reports on a miscarriage of justice that destroyed the lives of the men and their families, and what it reveals about the state of the criminal justice system in the country.

Five of the six men lived on death row for 13 of the 16 years they were in prison.

The sixth, a juvenile at the time of the crime, was also initially tried as an adult and given the death sentence. He was freed in 2012 after it was proved that he was only 17 at the time of the murders.

The men on death row were holed up in tiny, windowless solitary cells with the shadow of execution over their heads. Light bulbs burnt harshly outside all night. The silence would be sometimes punctuated by the piercing screams of fellow prisoners.

One of them said life on death row felt like a "cobra sitting on my chest". Another said he had nightmares about "ghosts of executed men". For the few hours he was let out during the day, he saw fellow prisoners having epileptic seizures, and a prisoner taking his own life. He battled ulcer pains and received little medical help. "He has lived in sub-human conditions under perpetual fear of death for several years," two doctors who examined the young man reported.

The six - Ambadas Laxman Shinde, Bapu Appa Shinde, Ankush Maruti Shinde, Rajya Appa Shinde, Raju Mhasu Shinde and Suresh Nagu Shinde - were aged between 17 and 30 when they were convicted for murdering five members of a family of guava pickers in an orchard in Nashik in the western state of Maharashtra in 2003. Ankush Maruti, who was 17, was the youngest.

Falsely implicated

June 2006 - Trial court in Pune sentences all six to death

March 2007 - Bombay High Court upholds the convictions, but commutes the death penalty of three to life

April 2009 - Supreme Court dismisses appeals and restores capital punishment for all six

October 2018 - Supreme Court allows review of its verdict

March 2019 - Supreme Court overturns its own verdict, saying all six men were falsely implicated

The Shindes are nomadic tribespeople and among India's poorest. They dig earth, pick rubbish, clean drains and work on other people's farms for a living. Seven judges in three courts over 13 years had found them guilty.

And they were all wrong.

Bapu Appa Shinde says he feels weak all the time

When the Supreme Court overturned the convictions it was a landmark judgment. For the first time in its history, India's top court had thrown out its own death penalty verdict.

The judges said the men had been falsely implicated and the courts had committed a grave error. They said there had been no "fair investigation and fair trial", and the rights of the accused had been violated.

"We strongly deprecate the conduct of the police and the prosecution," the judges added in an extraordinary 75-page verdict. "The real culprits had gone free."

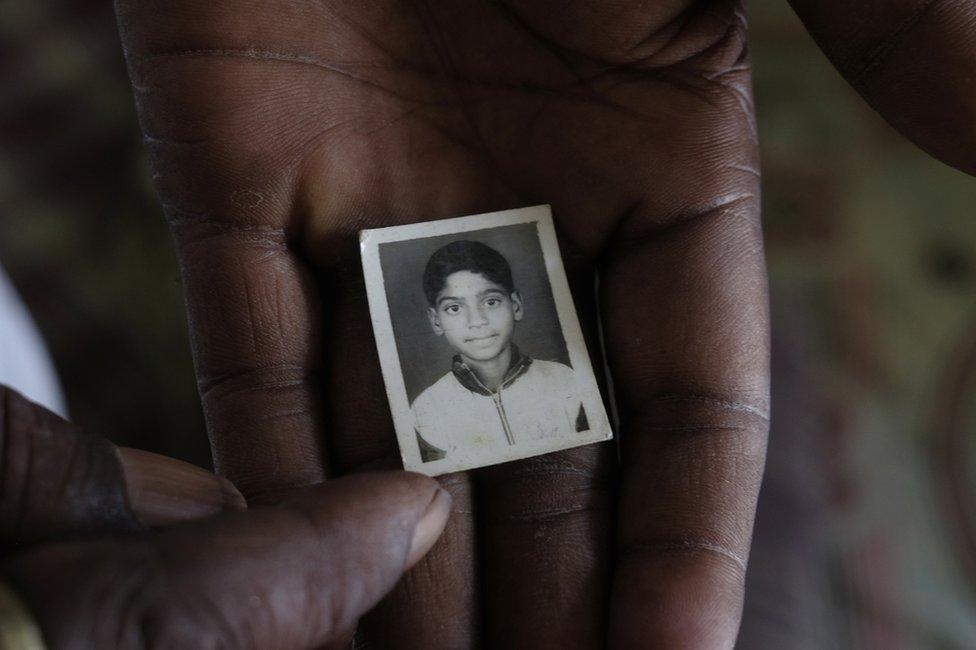

Raju Shinde was 15 when he was electrocuted while working

The Supreme Court's exoneration of the men happened a decade after it had dismissed their appeals.

The judges said there had been "sheer negligence or culpable lapses" in investigating the case and said action should be taken against erring police officials. Compensation of 500,000 rupees ($7,176; £5,696) was awarded to each of the men, to be paid within a month, and to be used for their "rehabilitation". (That's 2,600 rupees for every month lost in prison.)

When I visited the six men - two of them are brothers and the rest, cousins - recently in Bhokardan, an arid, drought-hit village in Jalna district, in Maharashtra, they were struggling with depression and anxiety. The compensation money had still not arrived.

Rajya Appa Shinde's wife left him when he was in prison

Death row, they said, had distorted their sense of time, numbed their senses, slowed them down, and made it difficult to return to work. They continued to suffer from high blood pressure, sleeplessness, diabetes and complained of failing eyesight. Days passed in a haze of cheap alcohol. Some of them were on sleeping pills and anti-depressants.

"I take half-a-dozen pills every day, and still feel weak. I go to the doctor and he puts me on a saline drip to keep me moving," Bapu Appa Shinde, 49, said.

"Prison kills you slowly and stealthily. When you get out, freedom becomes painful."

When the men went to prison, their wives and children were forced to work, cleaning drains and wells and collecting rubbish. Most of the children did not go to school. In a region strangled by years of drought, there was very little farm work available.

Nothing, say the men, will compensate for the tragic costs of incarceration for their families.

In 2008, Bapu Appa's 15-year-old son, Raju, was electrocuted after the spade he was using to dig a ditch came in contact with a live cable. "He was the smartest child in the family. He wouldn't have been working in the streets if I was not in prison."

When Bapu Appa and his brother Rajya Appa returned from the prison, they found their decrepit family home reduced to a heap of rubble. Their families were sleeping in the open under a tree and in an abandoned single-storey government building. Their children had built a tin shack to welcome their fathers.

"We are now free but homeless," Rajya Appa said.

The wife of Rajya Appa Shinde - they were married three months before he was picked up by the police - left him for another man 12 years ago without telling him. "She came to see me in prison 12 days before she went off with another man. She didn't tell me she was leaving. Maybe she was under pressure from her family," he says. He remarried recently.

Two of the men lost their parents, who suffered from heart attacks when they heard the news that their sons had been sent to death row.

Their impoverished families would travel, often without tickets, to Nagpur for brief prison meetings. "If the ticket collector caught us, we would tell them our husbands are in prison, we are poor, we have no money. Sometimes they would throw us off the train, sometimes they would show mercy. There is no dignity when you are poor," Rani Shinde, one of the wives, said.

Suresh Shinde stays in a hut and has not found work yet

"Everything was stolen from us. Our lives, livelihoods. We lost everything for something we didn't do," said Raju Shinde.

The six men were found guilty of killing five members of the same family in a hut in a guava orchard in Nashik on the night of 5 June 2003. Nashik is more than 300km (186 miles) away from where the Shindes lived.

Two members of the family - a man and his mother - survived the attack. They told the police that "seven to eight" men carrying knives, sickles and sticks entered the hut, which had no electricity. They spoke in Hindi, and said they had come from Mumbai. They turned up the volume of music which was playing on a battery-operated cassette player and demanded the family turn over their money and jewellery.

According to the two eyewitnesses, they turned over money and jewellery worth 6,500 rupees to the men. The attackers drank liquor and then attacked them, killing five, including two women. One of the dead women was raped. The victims were aged between 13 and 48.

The police found the blood splattered bodies next morning. They picked up cassette tapes, a wooden stump, a sickle, and 14 pairs of sandals from the hut. They also collected blood stains and picked up prints.

Ambadas Laxman Shinde finds it "difficult to sleep" at night

The day after the murder the police took a photo album of local criminals from their records and showed it to the woman who had survived the attack and become a prime eyewitness. She identified four men, aged 19-35, from the album and told a magistrate that they had killed her family members. "They were local criminals and were in the police records," a lawyer said.

The police and the prosecution, according to the Supreme Court, "suppressed this evidence" and did not pick up the four men.

Instead, three weeks later, they picked up the Shindes who lived far away and, as it transpired later, had never visited Nashik. The men say they were tortured in custody - given "electric shocks and beatings" - and forced to sign confessions.

And in a bizarre twist which eventually sealed their fates, the woman eyewitness now "identified" the Shindes as the murderers in a police line-up where people are identified by witnesses from a row of suspects.

In 2006, the trial court found the six men guilty of murders and sentenced them to death. Four different police officers led the investigations and the prosecution examined 25 witnesses.

The Shinde brothers found that their home had been reduced to rubble

Over the next decade and more, the high court in Bombay and the Supreme Court upheld the convictions. India's top court actually restored the death penalty of three men, after the Bombay High Court had commuted them to life sentence.

The courts ignored a mountain of evidence which proved that the Shindes were not linked to the killings.

The prints found in the hut and outside didn't match them. Blood and DNA samples were taken from the brothers, but the prosecution never presented the results in the court. "It seems the results did not incriminate the accused," the judges said in March, while freeing the men. No stolen property was found from them.

The eyewitnesses had told the police that the assailants spoke in Hindi, but the Shindes spoke the Marathi language.

Ankush Maruti Shinde was 17 when he went to prison

Mumbai-based lawyer Yug Chaudhry looked at the evidence - or the lack of it - and fought a decade-long battle to keep the six men alive.

He filed clemency petitions on their behalf to the governor, the president and the advocate general. He got former judges to write a letter to the president of India, requesting him to commute to life the death sentences of 13 men, including the Shindes. The judges wrote that "execution of persons wrongly sentenced to death would severely undermine the credibility of the criminal justice system".

Sixteen years after the unresolved crime, there remain a number of vexing unanswered questions.

How did the courts find the Shindes guilty and sentence them to death on the basis of dodgy eyewitness identification and nothing else? Lawyers say since this was a "heinous crime", the judges were under pressure from the public and the media, who were demanding a quick closure.

Raju Shinde says he drinks often because he feels "tense all the time"

Why did the police not arrest and investigate the four men in their files who were initially identified by the eyewitness? There is no explanation, the Supreme Court said.

Why did eyewitnesses change tack and end up identifying the wrong men? Was it a case of memory lapse or mistaken identity? Or were they coerced by the police? Nobody quite knows.

Most importantly, why did the police pick up six innocent men, living more than 300km away, and implicate them in the murder?

'Special surveillance'

Lawyers say the Shindes were framed because they were poor, nomadic tribes-people, who were once considered a "criminal tribe" under a controversial colonial law which targeted caste groups considered to be hereditary criminals. India's police manual explicitly says such communities should be kept under "special surveillance" and that their members be treated as "suspicious characters".

Also, three of the men had been framed before in another murder which had happened a month before the Nashik killings - the courts found them innocent and freed them in 2014.

The three judges who acquitted the men appeared to agree.

"The accused are nomadic tribes coming from the lower strata of society and are very poor labourers. Therefore, false implication cannot be ruled out since it is common occurrence that in serious offences innocent people are roped in," they wrote in the verdict.

In the end, the fate that befell the Shindes underscores the weakness of India's criminal justice system and how heavily it is loaded against the poor.

Rani Shinde's three daughters were the only children in the family who went to school

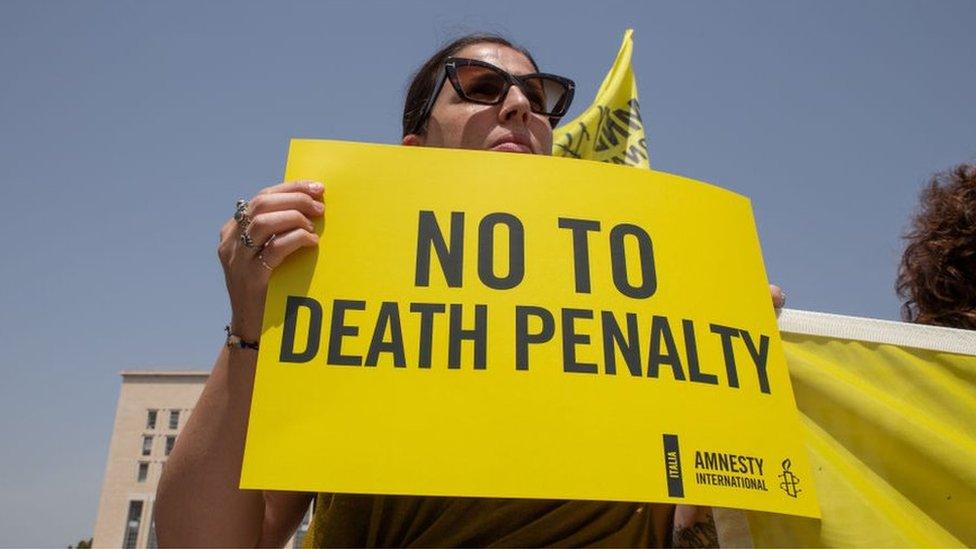

"The suffering inflicted on them shows the perils of having the death penalty in the midst of such an error-prone criminal justice system," says Anup Surendranath, who teaches law at the Delhi-based National Law University.

"If three courts, including the apex court, could not spot the illegalities perpetrated by the investigating authorities in framing six innocent men, then there is no reasonable way to hold the position that we have a criminal justice system capable of having the death penalty," he adds.

India has some 400 people on the death row.

Photographs by Mansi Thapliyal

- Published1 November 2018

- Published25 January 2024

- Published29 August 2012