India coronavirus: Why celebrating Covid-19 'success models' is dangerous

- Published

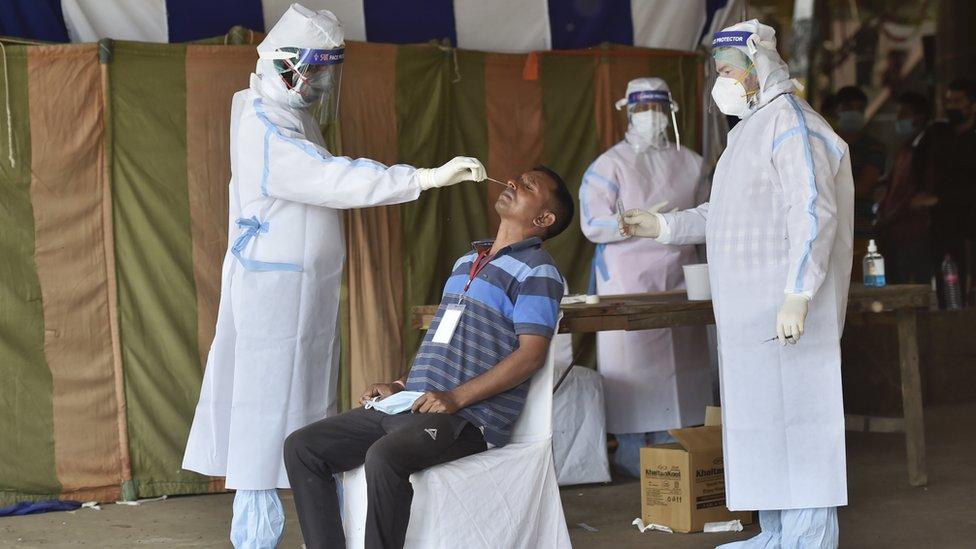

Experts say that mass testing will help officials plan better

As India continues to fight the spread of coronavirus, a few 'successful' efforts at containing the infection have been touted as 'models', celebrated and mimicked across the country. But experts say such premature euphoria can be dangerous. The BBC's Vikas Pandey reports.

The northern Indian city of Agra, home to the iconic Taj Mahal, was one of the first Indian cities to report a positive case of coronavirus back in early March.

It continued to report cases throughout the month but managed to slow down the spread - and that is how the "Agra model" was born.

It trended as a hashtag on social media, the federal government was full of praise and Uttar Pradesh state chief minister Yogi Adityanath was credited for its success.

But things changed within days. As the month of April started, the number of cases started doubling quickly and the early success started to unravel. The model had relied heavily on strictly containing affected areas and isolating suspected cases. But as the virus spread to newer areas, authorities had to look for other options, like aggressive testing.

The city now has more than 600 cases - more than any other city in the state and the much-feted Agra model disappeared from the news cycle.

It just goes to prove such early celebrations involve "great risks", says prominent virologist Dr Shahid Jameel.

Agra has seen a sharp rise in the number of cases

"Such euphoria makes people let their guard down and that can be dangerous," he says.

Several experts, including Dr Jameel, point out that there is so little known about the novel coronavirus, the existence of which was only discovered late last year, meaning scientists haven't had enough time to study it properly.

"That makes Covid-19 so dangerous," he adds.

Take, for example, the discovery that "the virus can be found in the sputum" of those affected for up to 30 days.

"So you can't feel victorious even after you have successfully treated all your patients. Being vigilant is the only option."

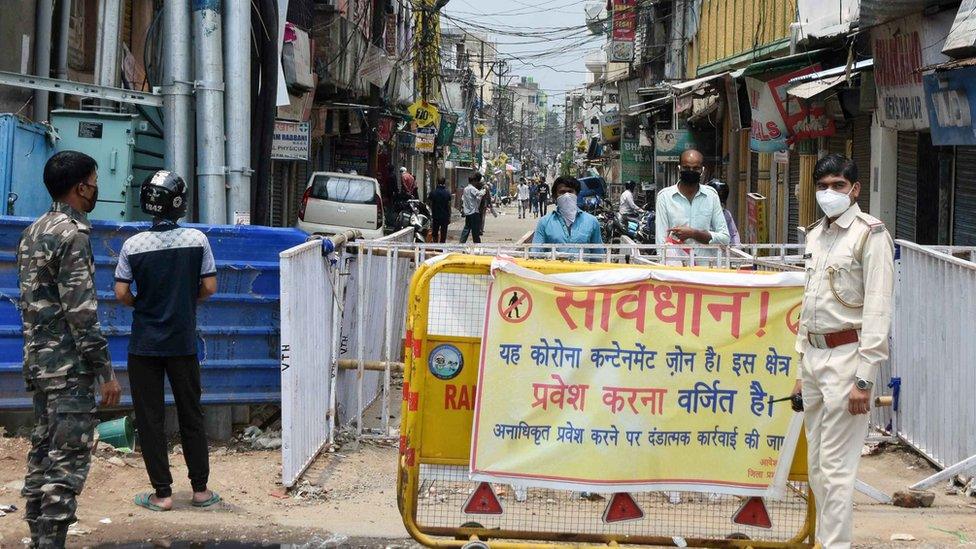

Classifying affected areas as containment zones has helped officials

In Agra, authorities were quick to define containment zones and they went for aggressive contact tracing.

"But it didn't call for a celebration because it ran the risk of undoing all the good work authorities had done," Dr Jameel adds.

Another problem of celebrating such models is that other states and districts rush to replicate it.

Epidemiologist Lalit Kant warns against such practice.

"Such models are area specific and cannot be replicated. One size doesn't fit all. We can of course learn from different models," he adds.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

CONTACT-TRACING APPS: Why are there doubts?

ENDING LOCKDOWN: The routes back to normal life

Take the example of Kerala: the state has been investing heavily in its healthcare network for years. When coronavirus hit the state, it was well prepared.

Officials were quick to identify, isolate and treat patients. It also used technology in contact tracing and also in finding suspected hotspots quickly to halt the spread.

But does that make Kerala a success model?

Dr A Fathahudeen, who is the nodal officer for COVID-19 treatment in Ernakulam district, is against the idea of calling any place a success model yet.

Contact tracing has been an important part of the government's strategy

"We have seen resurgence of cases in some areas of Kerala. There are some cases where we haven't been able to find the source of the infection," he says.

He argues that things change "so fast with this virus" that nobody can afford to relax.

"If you celebrate such models, then you will have dead bodies to answer for."

Dr Fathahudeen says such models should be studied by scientists but they haven't had enough time to do that.

The problem starts, he adds, when "politicians start declaring successes without any scientific approval".

"They (politicians) often don't realise that what worked in Kerala will not work in a densely populated slum like Dharawi in Mumbai," he said.

People are not allowed to leave containment zone

Indeed, Dr Kant believes that most of these models rely on "containing people from going out", but we are still "far away from containing the virus".

"So that distinction has to be made," he says. "Behaviour of individuals, population density, travel history and health infrastructure - all these factors come into play. So, models can be adapted, but not adopted."

Public health expert Anant Bhan agrees. He believes that each state, and possibly each district, needs to evaluate its own response.

"There can't be a uniform model in such a diverse country like India," he adds.

Mr Bhan says that euphoria over such success models can also put frontline workers at risk.

"The possibility of complacency become real when people, including frontline workers, get false hope of a success," he adds.

And that is why you need to acknowledge and learn from the positives when any place does well, but "definitely not celebrate it as an end".

Several Indian states have been trying to ramp up testing

The state of Rajasthan is an example that shows why one model cannot be applied in two places. While the state government has been able to contain the spread in the town of Bhilwara, it has struggled to do the same in the capital Jaipur, which has been ravaged by the virus.

And then there are global models that have also been celebrated, and Singapore is one of them, external.

Headlines across the world congratulated Singapore for containing the spread. But the country saw a second wave and had to announce a lockdown.

Dr Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious diseases expert at Singapore's Mount Elizabeth Novena hospital, says Singapore did well with measures like social distancing.

"But this virus is sneaky, the risk was always there and it made a comeback," he adds.

He adds that "shortcuts or celebrations" can quickly come back to haunt you.

"All it takes is a super-spreader to reverse your success and no country in the world can afford to do that."

- Published4 May 2020