Churchill's legacy leaves Indians questioning his hero status

- Published

I first learnt about Winston Churchill as a child. A character in an Enid Blyton book I was reading kept a picture of him on the mantelpiece in her home because she 'had a terrific admiration for this great statesman'.

As I grew older, and had more conversations about India's colonial past, I found most people in my country held a starkly different view of the wartime British prime minister.

There were conflicting opinions about colonial rule too.

Some argued the British had done great things for India - built railways, set up a postal system. "They did those things to serve their own purpose, and left India a poor, plundered country" would be the inevitable response to this claim. My grandmother always talked passionately about how they'd participated in protests against "those cruel Britishers".

But despite this anger, anything western, anything done or said by people who were white-skinned, was seen as superior in the India I grew up in. The self-confidence of people had been eroded by decades of colonial rule.

Seventy-three years since independence, a lot has changed. A new generation of Indians, more self-assured about our place in the world, are questioning why there isn't more widespread knowledge and condemnation of the many dark chapters of our colonial history, like the Bengal famine of 1943.

At least three million people died of hunger. That's more than six times the British Empire's casualties in World War Two. But even as the war's victories and losses are commemorated each year, the disaster that unfolded in British-ruled Bengal during the same time has largely been forgotten.

Bengal famine: Remembering WWII's forgotten disaster

10 greatest controversies of Churchill's career

MSP makes Churchill 'mass murderer' claim

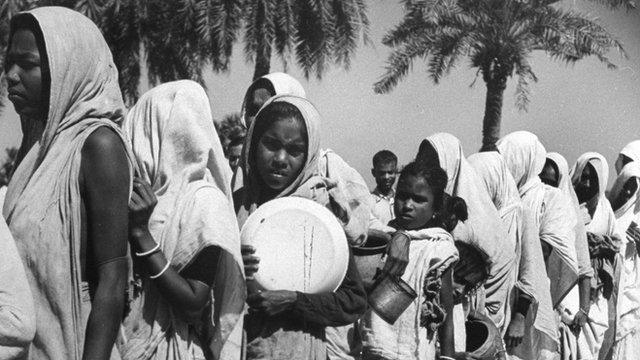

Eyewitnesses have recounted how dead bodies lay in fields and near rivers, being eaten by dogs and vultures because no-one had the strength to perform last rites for so many people.

Those who didn't die in villages journeyed to towns and cities in search of food.

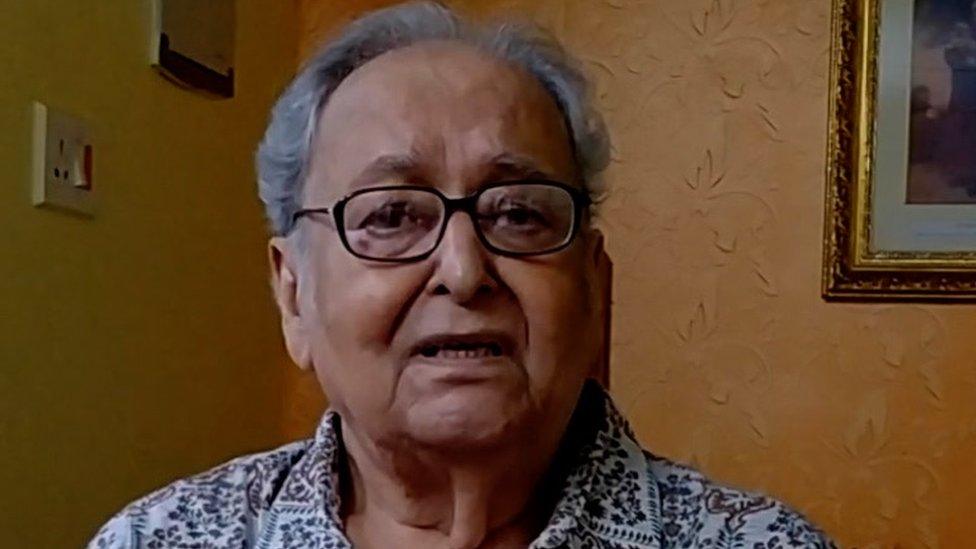

Bengali actor Soumitra Chatterjee says he is still haunted by memories of the famine

"Everyone was looking like a skeleton with just skin over their frames," says veteran Bengali actor Soumitra Chatterjee who was eight when the famine struck.

"People would cry pitifully, asking for the liquid that came out of cooking rice, because they knew nobody had any rice to give them. And anyone who has heard that cry will never forget it in their life. There are tears in my eyes now when I'm speaking about it. I can't check my emotions," he told me.

A cyclone and flooding in Bengal in 1942 triggered the famine. But the policies of Sir Winston Churchill and his cabinet are blamed for making the situation worse.

Yasmin Khan, a historian at Oxford University, describes the 'denial policy' that was implemented fearing a Japanese invasion from Burma.

"The idea was that things would be razed to the ground, including crops, but also boats that could be used for transportation of crops. And so that when the Japanese came, they wouldn't have the resources to be able to expand their invasion. The impact of the denial policy on the famine is well evidenced," she says.

Churchill statue 'may have to be put in museum'

Calls to remove 'racist' Gandhi statue in Leicester

Diaries written by British officers responsible for India's administration show that for months Churchill's government turned down urgent pleas for the export of food to India, fearing it would reduce stockpiles in the UK and take ships away from the war effort. Churchill felt local politicians could do more to help the starving.

The notes also reveal the British prime minister's attitude towards India. During one government discussion about famine relief, Secretary of State for India Leopold Amery recorded that Churchill suggested any aid sent would be insufficient because of "Indians breeding like rabbits".

"We can't blame him for creating the famine in any way," says Ms. Khan. "What we can say is that he didn't alleviate it when he had the ability to do so, and we can blame him for prioritising white lives and European lives over South Asian lives which was really kind of unpleasant given the millions of Indian soldiers at the same time also serving in the Second World War."

Some in the UK claim that while Churchill might have made unsavoury comments about India, he did try to help and delays were a result of conditions during the war.

But millions perished under his watch, for the lack of the most basic of all necessities - food.

Archibald Wavell, Viceroy to India at the time, has described the Bengal famine as one of the greatest disasters to have befallen people under British rule. He said the damage it caused to the empire's reputation was incalculable.

Survivors say they feel angry. "There is an undercurrent of expectation that it's time the British government comes out and says sorry for what was done to India in those days," says Mr Chatterjee.

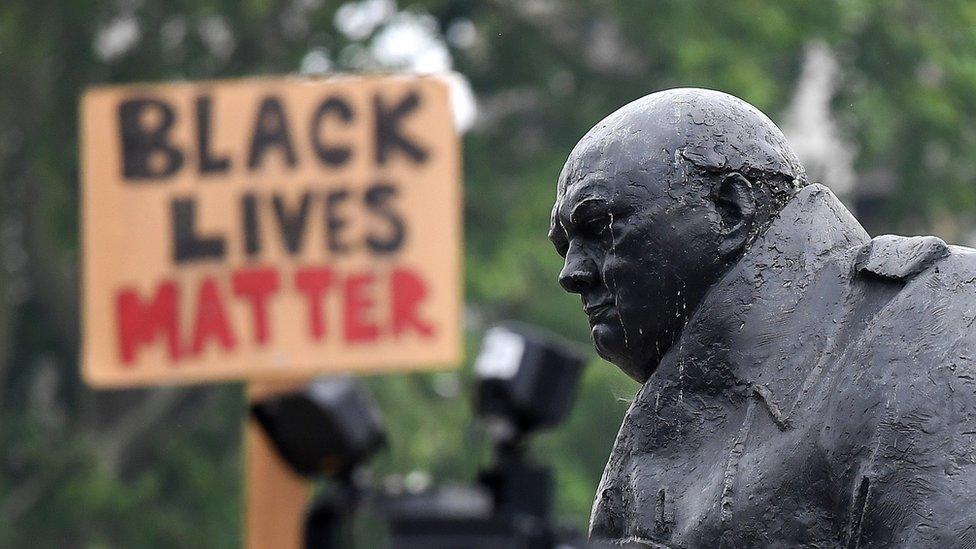

Protestors spray-painted the Churchill statue with the words 'was a racist'

Many in the UK too are questioning the legacy of colonial rule, and its leaders.

Last month, during a protest that was part of the Black Lives Matter movement, Churchill's statue in central London was defaced.

"I am not in favour of pulling down or defacing statues," says Indian historian Rudrangshu Mukherjee.

"But I think in the plaque below the statues, the full history should be recorded, that Churchill was a hero in the Second World War, but that he was also responsible for the deaths of millions of people in Bengal in 1943. I think Britain owes that to Indians and to itself."

Judging the past through the lens of the present might leave the world with no heroes at all.

India's most loved independence leader Mohandas Gandhi has also been accused of having anti-black views.

But it's hard to make progress without the acceptance of the full truth of their lives.

The works of my childhood icon Enid Blyton have faced a big backlash for being racist and sexist. As an adult, I have looked through the dog-eared stash my sister and I left at our parents' home, and I can see evidence of the allegations.

Would I throw them all out?

No. The happy memories they evoke are not tainted by what I now know.

But I won't pass them on to the children in my family. They deserve to read stories set in a more equal world.

Read more stories about the legacies of British colonial rule and how it is still affecting people today:

- Published1 April 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published17 September 2015

- Published28 January 2019