Why India’s Covid problem could be bigger than we think

- Published

Life in India has resumed even as cases surge

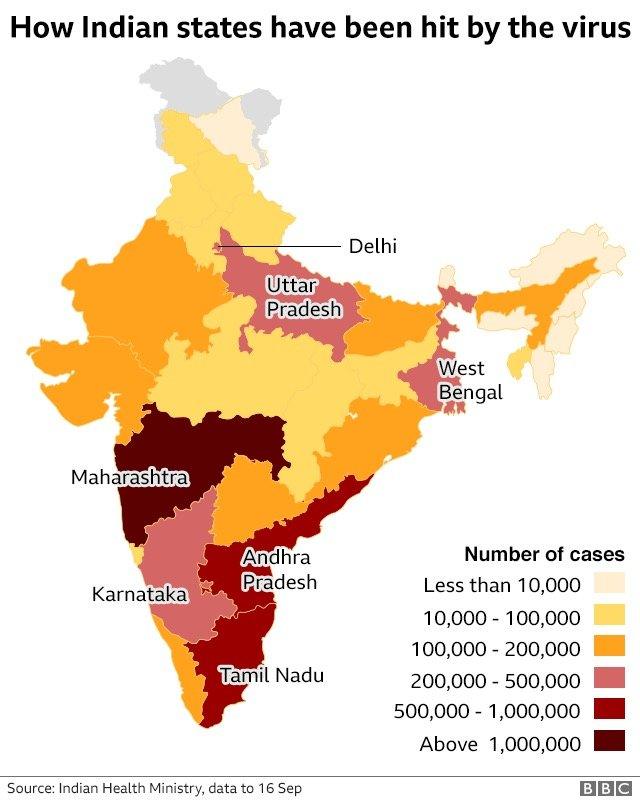

India is approaching the ninth month of the coronavirus pandemic with more than five million confirmed cases - the second-highest in the world after the US - and more than 80,000 reported deaths.

Infection is surging through the country in a "step-ladder spiral", a government scientist told me. The only "consolation" is a death rate - currently 1.63% - that's lower than many countries with a high caseload.

The increase in reported cases has partly to do with increased testing - but the speed at which the virus is spreading is worrying experts.

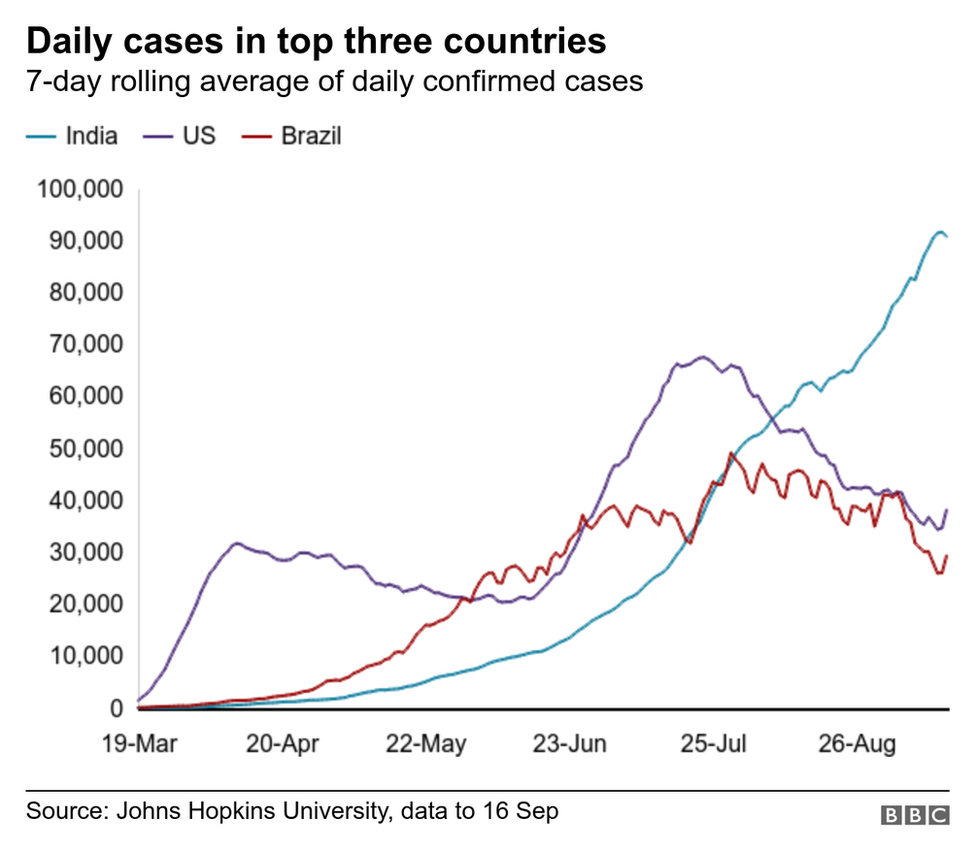

Here's why. It took 170 days for India to reach the first million cases. The last million cases took only 11 days. Average daily cases have shot up from 62 in April to more than 87,000 in September.

In the past week, India has recorded more than 90,000 cases and 1,000 deaths every day. Seven states are worst affected - accounting for about 48% of India's population.

But even as infections soar, India is opening up - workplaces, public transport, eateries, gyms - to try to repair a battered economy suffering its worst slump in decades.

The world's most draconian lockdown forced people to stay at home, shut businesses and triggered an exodus of millions of informal workers who lost their jobs in the cities and returned home on foot, buses and trains.

But the resumption of economic activity even as cases spiral suggests "lockdown fatigue", the Nomura India Business Resumption Index says.

Infection numbers may be much higher

More than 50 million Indians have been tested so far for the virus, and more than a million samples are being tested daily. But the country still has one of the lowest testing rates in the world.

So epidemiologists suggest that India's real infection rates are far higher.

The government's own antibody tests on a random sample of people nationwide estimate 6.4 million infections in early May, as compared to the recorded case count of 52,000 around that time.

Bhramar Mukherjee, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the University of Michigan who has been closely tracking the pandemic, says her models point to about 100 million infections in India now.

"I think India has taken a path of cruising towards herd immunity. I am not sure whether everyone is following preventive measures like wearing masks and keeping social distancing seriously," she told me. Herd immunity is achieved when enough people become immune to a virus to stop its spread.

"This could be due to habituation, desensitisation [to the disease], fatigue, denial, fatalism or a combination of both. It feels like a thousand deaths a day have become normal."

India has expanded testing significantly

As long as infections spiral, a full recovery of the economy is delayed, and hospitals and care centres may continue to get overwhelmed by surging caseloads.

K Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India, a Delhi-based think tank, describes the present surge of infections as a "first tide rather than a first wave".

"The waves are moving outward from the initial points of origin, with different timings of spread and levels of rise. Together, they constitute a high tide which is still to show signs of ebbing."

Why are rates still soaring?

"With increased mobility and reduced adherence to social distancing, mask wearing and personal hygiene, the virus will soar again," says Dr Mukherjee.

A doctor in a large hospital in Jodhpur in Rajasthan told me they were seeing a surge in severely sick elderly patients who lived in joint families.

More than 80,000 people have died of Covid-19 in India, official figures show

Way back in March, Dr T Jacob John, a prominent virologist, had warned that an "avalanche of a pandemic" awaited India.

In many ways, a high number of cases in a vast country with a creaky public health system was "inevitable", he says now. But, such a high number of infections could still have been avoided, he adds, blaming a badly-timed lockdown.

Read more stories by Soutik Biswas

Most experts agree that a partial and well-managed lockdown in the few cities where infection had broken out would have been better.

"It failed because it did exactly what a lockdown should not do," says Kaushik Basu, former chief economist of the World Bank. "It caused a mass movement of people walking all over the nation, trying to reach home, because they had no choice. As a result, India's economy got damaged and the virus continued to spread."

Millions of people in India have lost their jobs during the pandemic

But public health experts like Dr Reddy say lives were saved.

"It is not easy to judge the timing of a lockdown in retrospect, as even the criticism in UK is that the lockdown was delayed and an earlier lockdown could have saved more lives."

'Every death is the face of a loved one'

Whatever its efficacy, the lockdown did help India to buy time to learn more about the virus and set up treatment protocols and surveillance systems that did not exist in March, epidemiologists say.

As winter approaches, the country now has more than 15,000 Covid-19 treatment facilities and more than a million dedicated isolation beds.

There are no reported shortages of masks, protective gear and ventilators as was the case in March. Oxygen supplies have, however, been patchy in recent weeks.

"Strengthening our healthcare and Covid-19 treatment facilities have helped with keeping the fatality rate low," says Dr Mukherjee.

However, the pandemic has stressed India's already-weak public health system to breaking point.

Doctors are working in special Covid-19 wards across the country

"If we are to understand pandemic fatigue and resilience in this moment of crisis, we must remember that public health workers, patients and families were already doing their best to manage infectious and chronic diseases in India with limited resources," Dwaipayan Banerjee, a medical anthropologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said.

In other words, fatigue and resilience are endemic to India's public health system.

But doctors and health workers have worked for months without a break.

"It's unrelenting, we are exhausted," says Dr Ravi Dosi, who has treated more than 4,000 Covid-19 patients in a private hospital in the central city of Indore. He says he has been working more than 20 hours a day since March.

And already deep cracks in the public health system have been exposed, not least by the spread of infection from cities to villages.

People are being urged to wear masks in public to curb the spread of the virus

Dr Mukherjee believes that this "will grow at a slow and steady rate until all the states come to a state of containment".

What India needs is co-ordinated long-term federal strategy, not headline management by the government, she says.

Her only hope is that the infection fatality rate - the ratio of deaths divided by the number of actual Covid-19 infections - remains low.

"However even with an infection fatality rate of 0.1%, if 50% of India gets infected, we will have 670,000 deaths. Every death is the face of a loved one, not a mere statistic."

In India some suspected coronavirus patients are turned away from hospitals

What do I need to know about the coronavirus?

ENDGAME: When will life get back to normal?

EASY STEPS: What can I do?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- Published18 August 2020

- Published16 September 2020