Coronavirus: What's driving India's 100,000 Covid-19 deaths?

- Published

A municipal worker sanitises a graveyard in India after the burial of Covid victims

India has confirmed more than 100,000 deaths from the coronavirus - a grim toll that ranks it third in the world behind only the US and Brazil.

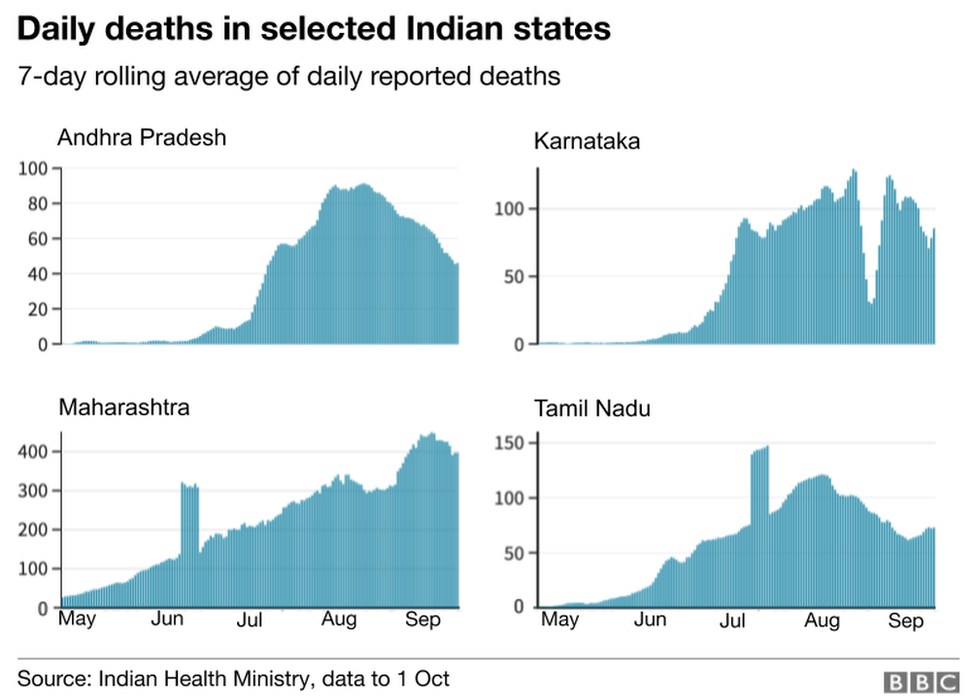

September was the nation's worst month on record: on average 1,100 Indians died every day from the virus. Regional anomalies continue as some states report far higher deaths than others - a sign, experts say, that the pandemic is still working its way through the country.

Here's some of what we know about where India is worst affected by Covid-19 and why.

Maharashtra is at the top of the list

Maharashtra, one of India's largest and richest states, has both the highest caseload - 1.3 million and counting - and death toll - more than 36,000.

The pandemic struck early in Maharashtra, spread quickly and barely let up. The number of daily reported deaths in September ranged between 300 and 500 - significantly higher than other badly-hit states which reported fewer than 100 deaths a day through the month.

And it is no longer Mumbai, the crowded financial hub, that is worrying pandemic watchers. Mumbai is still the district with the highest fatalities, but quiet, suburban Pune district has raced to second place with more than 5,800 deaths. Five of the 10 districts with the highest Covid-19 fatalities - Mumbai and Pune included - are now in Maharashtra.

Mumbai was the virus' gateway to Maharashtra, said Dr Aurnab Ghose, who was part of a team which carried out a random antibody sampling of Pune residents. The government survey found that, in some parts of the city, half the people had developed Covid-19 antibodies.

Dr Ghose said that while Mumbai was more self-contained, the greater movement between urban and rural parts of Pune district, as well between Pune and surrounding districts, had spread the virus further in these parts.

And given the high prevalence, health systems too have been overwhelmed, driving up deaths in some instances. Pune's 'jumbo' Covid centre made headlines, external recently over allegations of a negligent death.

Punjab is getting worse

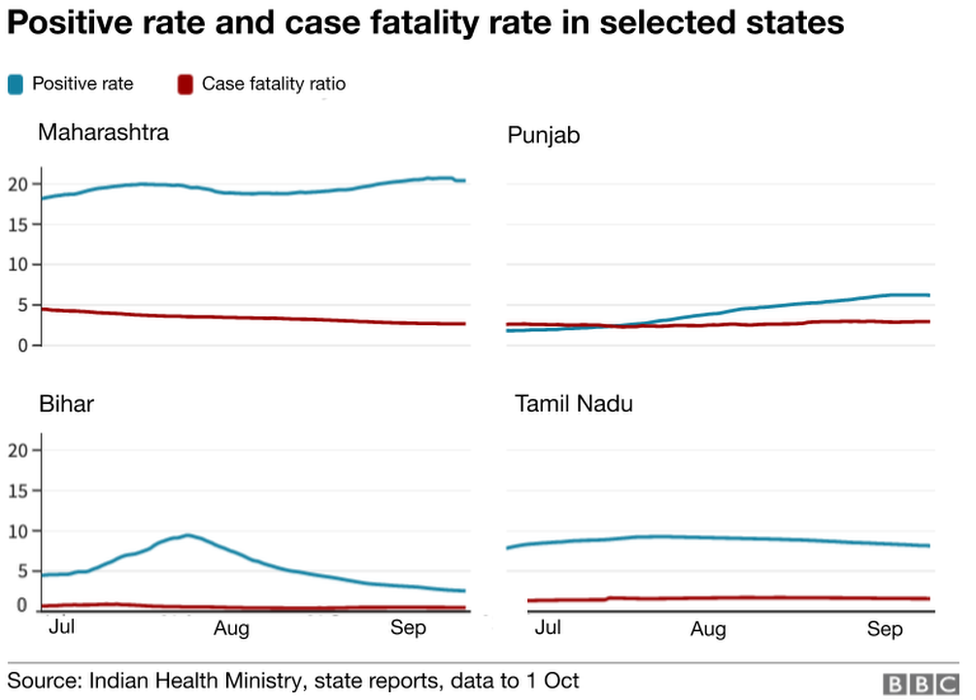

The northern state has been reporting a case fatality ratio of 3%. That's a measure of how many Covid positive patients die from the virus and Punjab's figure is double that of India's national average.

In absolute numbers, the state ranks ninth for deaths. But many of its districts are also reporting high case fatality rates - 4% and above.

"Punjab is a cause for concern," said Dr Shamika Ravi, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who is tracking the pandemic. "Its case fatality rate is not only the highest in the country but it's also rising," she said.

India's health services have been struggling to cope with the number of cases

That is alarming, Dr Ravi said, because it is contrary to what's happening all over the world and in India as a whole - widespread testing and improved knowledge of treatment options is bringing down case fatality rates.

Dr Ravi said she believed Maharashtra and Punjab were both showing symptoms of a bigger malaise - limited testing, leading to higher positive rates. Lower testing could leader to a rise in death rates, she said, because authorities catch the infection only when it's too late.

Is testing the problem?

Punjab's positive rate - at 6.2% - is significantly lower than that of Maharashtra - 24%. But it's also much higher than Bihar (2.5%) or Jharkhand (3.7%) - states that are doing about the same number of tests per million as Punjab - 60,000. And yet their positive rates are far lower.

"If you test less and your positive rate is still high, it means the infection is way ahead. You are catching cases too late," Dr Ravi said.

Her argument was backed up by the picture in Maharashtra, she said - a state that has consistently reported high positivity rates, high deaths, but has not ramped up testing significantly.

Not everyone is convinced of the correlation between the two. "I don't know of any direct relationship," said Dr Gautam Menon, a professor and researcher on models of infectious diseases. "You're not testing enough means you're missing a ton of cases. But what fraction of those cases lead to deaths is hard to say."

Dr Ghose said he thought there could be a more roundabout link - that lesser awareness and ability to get tested - which results in limited testing - could also lead to later hospitalisations, increasing the chances of death.

A recent study in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, external found that the median time from hospitalisation to death among Covid-19 patients was 13 days, leading researchers to conclude that "a substantial proportion of patients" in the two states were likely diagnosed late.

And yet Tamil Nadu is a state that has been consistently testing at high rates, and also has a low case fatality rate. In absolute numbers, it has reported more than 9,000 deaths, the second-highest in the country, but daily deaths have been falling since July.

But Dr Jacob John, an epidemiologist, said that was because diagnosing the infection early was not always going to affect a patient's treatment plan because in many cases, doctors follow that plan even without a diagnosis.

"For poor testing to have poor outcomes, one has to assume that testing will change the way a patient is managed," Dr John said.

Instead, a higher case fatality rate is the result of a poor health delivery system, he said, and the same system also delivers limited testing and treatment once someone ends up in a hospital.

Urban districts are reporting higher deaths

All 10 of the worst-hit districts so far are urban, and the same goes for those reporting the highest case fatality rates.

Urban districts have so far accounted for nearly 80% of India's death toll for the virus. Many of them have higher than average case fatality rates.

How Covid-19 has overrun Mumbai hospitals

This is not surprising given that the virus thrives in dense populations where social distancing is nearly impossible. And it also explains why most of the worst-hit districts are in richer states such as Maharashtra or Punjab. These states are far more urbanised, and many of the districts outside of the big cities are still home to large, concentrated populations.

Experts believe urban districts are also reporting higher fatalities because people from surrounding districts tend to travel to them for treatment.

"Pune data is clouded by the fact that there is a lot of inflow from surrounding districts," said Dr Gautam Menon, a professor and researcher on models of infectious diseases.

Rural districts also have lower co-morbidities, which would lower the risk of death from the virus, Dr Menon said.

Poorer states are registering lower deaths

Under reporting is certainly a factor but India's poorest states, which everyone feared would be overrun by the virus, have not yet buckled.

But we are not at the end of the pandemic yet, warned Dr Ghose. "The worst has passed for Maharashtra and, probably, Delhi but the rest of us have some way to go," he said.

"Each state is in a different point in the pandemic. Fortunately, it started out in richer states like Maharashtra. If it started out in Bihar, it would have been a disaster."

Read more of our coverage on the pandemic in India

- Published18 August 2020