Forced to undergo genital exams in colonial India

- Published

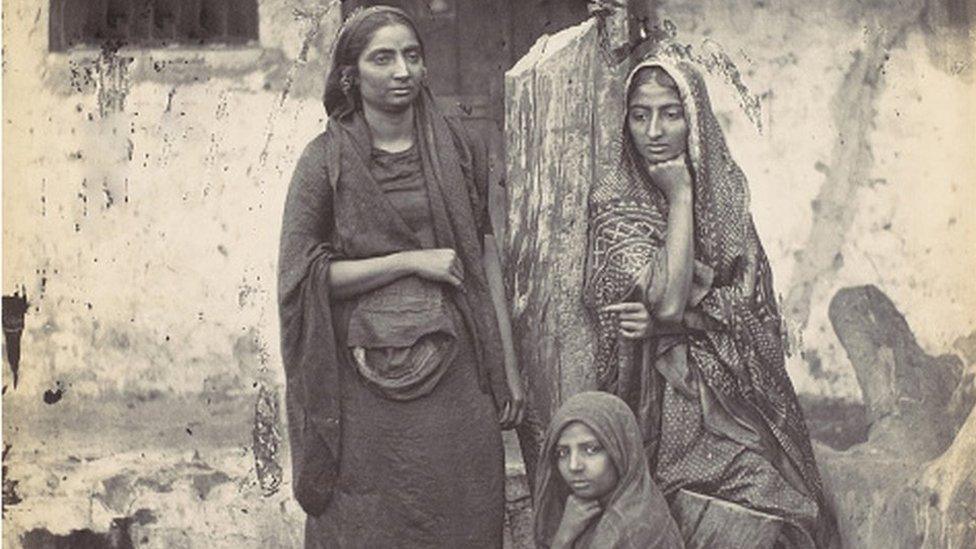

Women in India in 1870 - new research by a Harvard professor explores sexuality under British authorities

In 1868, police in the British-ruled Indian city of Calcutta (now Kolkata) sent a woman called Sukhimonee Raur to prison for evading a genital examination which had been made compulsory for "registered" sex workers.

Under the colonial Contagious Diseases Act, designed to contain the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, sex workers had to "register themselves at police stations, get medically examined and surveilled".

Raur fought back - she petitioned the court, demanding her release.

"I did not attend for examination twice a month as I have not been a prostitute," she said. She said the police had mistakenly registered her and that she had never been a sex worker.

In March 1869, the high court in Calcutta ruled in her favour.

The judges said that Raur was not a "registered public prostitute" and, moreover, such registration of women would have to be voluntary. In other words, women could not be forced to register.

Trawling the colonial archives, Durba Mitra, a professor of women, gender and sexuality at Harvard University, found that thousands of women were arrested by the colonial police for failing to abide by the rules of registration for genital examination mandated under the law.

Prof Mitra's new work Indian Sex Life, published by Princeton University Press, is a remarkable study of how British authorities and Indian intellectuals "developed ideas about deviant female sexuality to control and organise modern society in India". One way to regulate sexuality was by classifying, registering and medically examining women seen as prostitutes, she told me.

The so-called dancing women were categorised as "prostitutes"

In July 1869, some prostitutes of Calcutta petitioned the colonial authorities, accusing them of "violating their womanhood" by forcing them to register and undergo genital examination.

The women protested against the "process of hateful examination which is, in other words, gross exposure". They wrote that those caught by the police were "forced to expose themselves to the doctor and his subordinates… The sense of female honour is not wholly blotted from our hearts".

Authorities quickly rejected the petition.

Powerful city officials said the "clandestine prostitutes" who evaded registration were a threat to the new law. Regulating the prostitutes in Bengal was an almost impossible task, argued Dr Robert Payne, the chief of a key hospital in Calcutta. He said women should be registered without consent.

Between 1870 and 1888, says Prof Mitra, 12 women were arrested every day for breaching the law in Calcutta alone. Authorities noted that many women, discovering that they were under supervision, were fleeing the city.

The federal government debated whether the police in Bengal could legally carry out genital examination on women "who were accused of undergoing abortion and infanticide".

One magistrate felt that "false cases of rape and procuring abortion will largely increase without compulsory genital examinations of women". Another argued that securing consent from women for the examination could cripple the "administration of justice". In a letter to the secretary of Bengal, the city's police commissioner, Stuart Hogg, suggested women continued to infect men with venereal diseases because of the limitations of the law.

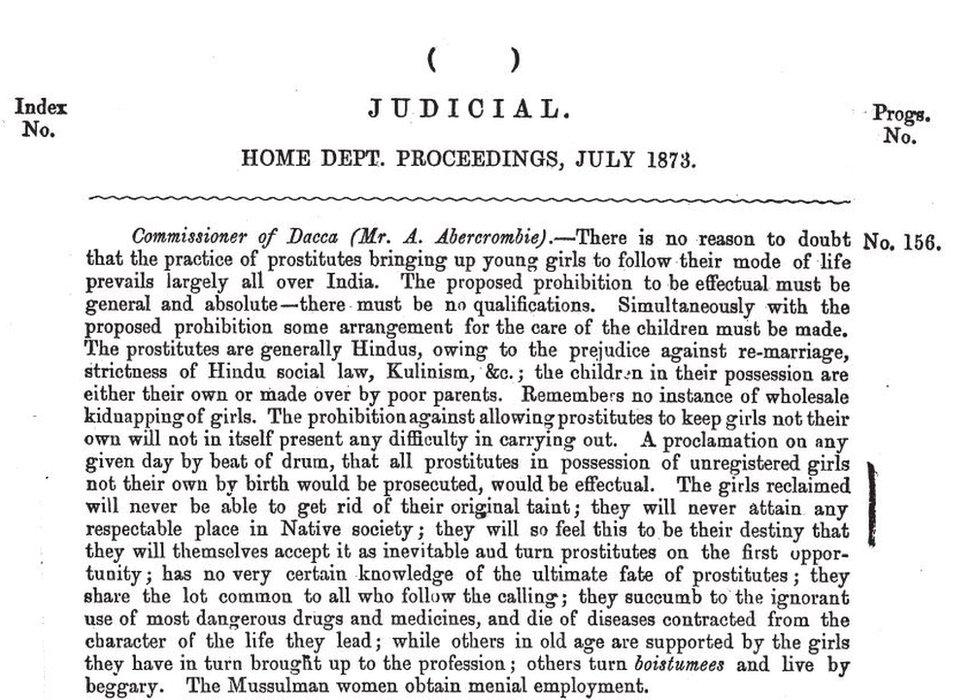

A British official's account of prostitutes in India

But with the growing opposition to the law in India and Britain, the offending Contagious Diseases Act was repealed in 1888.

Jessica Hinchy, a historian and author of Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India, said it was not suspected prostitutes alone who were subjected to genital examinations in colonial India.

She told me that people whom the British "classified with the pejorative colonial term 'eunuch', especially transgender Hijras" were subjected to genital examinations under a controversial 1871 law which targeted caste groups considered to be hereditary criminals.

"The aim of this law was to cause the 'gradual extinction' of Hijras - both physically and culturally - through police registration, prohibitions on performance and dressing in feminine clothes, forced removal of children from Hijra households and interference with Hijra discipleship and succession practices," Dr Hinchy said.

The Contagious Diseases Act is considered a shameful chapter in the history of colonial India.

Officials distributed questionnaires to magistrates, policemen and doctors on how to define a prostitute.

Colonial authorities, writes Prof Mitra, replied that all Indian women were potential prostitutes. A top police official, AH Giles, argued that all women who were not upper caste and married could be classified as a prostitute. Twenty volumes of a statistical account of Bengal between 1875 and 1879 repeatedly used the category of prostitutes.

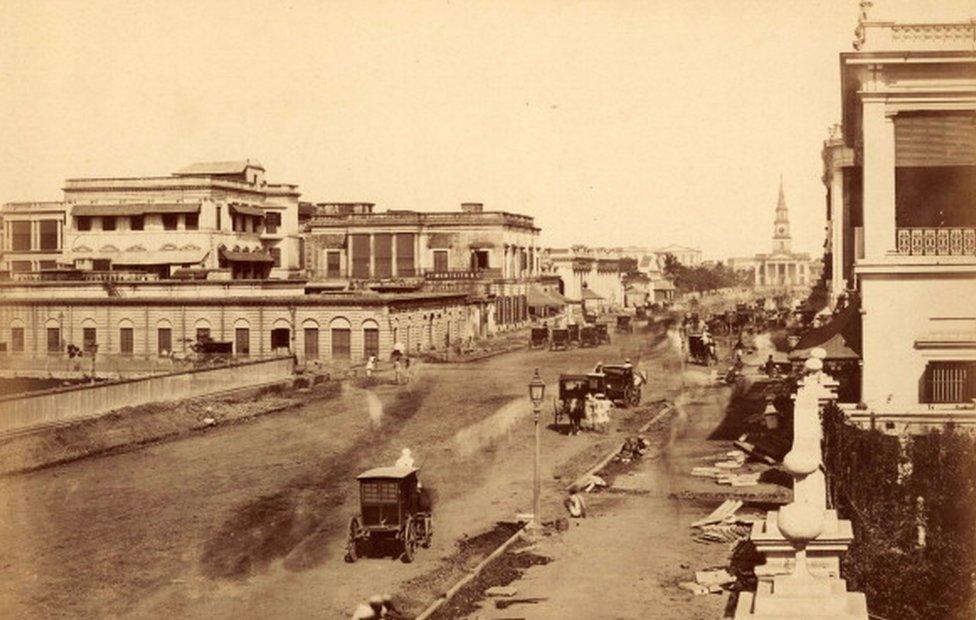

A street scene in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1870

Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, then a mid-level bureaucrat in Bengal who would eventually become a celebrated novelist and author of India's national song, detailed "a diverse array of women who practiced clandestine prostitution".

In colonial India, according to Prof Mitra, virtually all women outside of monogamous Hindu upper-caste marriages were considered prostitutes.

They would include so-called dancing girls, widows, both Hindu and Muslim polygamous women, beggars, vagrants, women factory workers and domestic servants. The 1881 colonial census of Bengal considered all unmarried women over the age of 15 as prostitutes.

The first census of the city of Calcutta and its neighbourhood counted 12,228 known prostitutes out of a population of 145,000 women. By 1891, the number rose to more than 20,000 women.

"The introduction of the act led to an epistemic shift, a pivotal change where Indian sexual practices became a primary object of knowledge for the British colonial state," says Prof Mitra.

An Indian house help with her European charges, 1870

But sexual practices of men remained almost entirely outside the formal purview of the state. Prof Mitra says the "control and erasure of women's sexuality became critical to how the British colonial state intervened in every day life".

Also, in places like Bengal, where she based her study, Indian men "also took up the control of women's sexuality in their own vision of Indian society that reorganised society along high-caste visions of Hindu monogamy, to the exclusion of Muslims and lower caste people".

At the root of all this was the notion that "deviant" womanhood was a problem that could not be easily solved. In the process, says Prof Mitra, women were "described, put on trial, scrutinised in public view, forcibly indentured, imprisoned, examined against their will". And so much of this history, she says, resonates with what is still happening with women.

- Published31 May 2019

- Published7 October 2018