Covid threatens to ground India's aviation industry

- Published

The national carrier had run out of money even before the pandemic set in

The pandemic has dealt a body blow to India's airlines, which had already been battling a broken pricing model and a domestic slowdown, writes the BBC's Nidhi Rai in Mumbai.

"I have sold my house and moved into a small apartment because I could no longer afford to pay my home loan," says a former pilot who wishes to remain anonymous.

The 38-year-old, who used to work for the state-run Air India, said he and his relatives were constantly harassed by the bank when he began defaulting on his payments.

"Bankers even came to my house and it was embarrassing for me. So I gave up my house in a distress sale. It was heartbreaking."

There was a time when flying for Air India was a lucrative career. In 2011, senior pilots were earning as much as 10 million rupees, external which, at the current exchange rate, amounts to more than $135,000 or £103,000.

But the country's flagship carrier is now bankrupt. It has been looking for a buyer for years - a prospect that has dimmed amid the pandemic, reportedly forcing the government to even consider wiping the airline's $3.3bn debt-tag from the deal.

Air India is not the only one in trouble. Indian aviation - once a promising industry with aspirational jobs - has been floundering in recent years. Seven airlines, including Jet Airways, India's oldest private carrier that was often hailed as a success story, shut shop in the past decade. And now Covid-19 is threatening the rest, compounding the effect of years of high fuel prices, heavy taxes, low demand and cut-throat competition.

Jet Airways staff demanded that the government save the airline before it went under

And it comes after a difficult year globally - in 2019, the grounding of the Boeing's 737 Max aircraft due to technical issues and Airbus' problems with its Pratt & Whitney engines hit airlines hard. Although lower aviation fuel prices offered some respite, it was not enough to recover long-term losses.

India currently has eight carriers, with Indigo leading the market. Air Deccan was the only airline which was forced to suspend operations in April, external, putting all its staff on leave without pay until further notice.

"Indian airlines are very precariously placed," says Kapil Kaul, South Asia CEO of CAPA - Centre for Aviation, an industry organisation.

The biggest challenge, experts say, is the slowdown in passenger traffic. India's stringent coronavirus lockdown, which lasted more than two months, stopped all air traffic. Although airlines have begun operating again, far fewer people are flying and international traffic is still severely curtailed.

Domestic passenger traffic between May and September 2020 was 11 million, down from more than 70 million for the same period the previous year, according to ratings agency ICRA. Traffic is expected to remain low in 2021 as well, ICRA vice president Kinjal Shah says.

Taking the last flight of India's stricken Jet Airways

So cash-strapped airlines are cutting jobs. Air India alone has let 48 pilots go this year and other airlines have sent many of their pilots on leave without pay or have slashed salaries up to 30%, says Praveen Keerthi, general secretary of Indian Commercial Pilots' Association. The International Air Transport Association estimated that India could see up to three million job losses in aviation and allied sectors such as airport services.

"It's the only option left," says Urvisha Jagasheth, a research analyst at Care Ratings. "The only cost which can be adjusted or tapered is salaries."

This is because revenue is now stagnant and operational costs - such as fuel, maintenance and airport charges for parking - are beyond their control.

Ms Jagasheth adds that the so-called budget airlines, such as Indigo or Air Asia, are no better off because they have been absorbing the costs they didn't pass on to passengers. Both airlines are looking to raise millions of dollars to get through the crisis.

India currently has eight carriers, with Indigo leading the market

"It's mentally very challenging to work in such uncertain times," says Amalendu Pathak, a pilot for a private airline. "But we have to keep working. I used to earn in millions and now I am earning $81 per hour. I have a family to feed. My savings are running out."

The situation is jut as bad for other employees in the industry. Ritika Srivastava, 34, used to work in the accounts division of a private airline. She quit her job for a similar role at a private airport company that was due to begin in March 2020. But the offer fell through because of the pandemic.

"They said they would call back once things normalise. It looks difficult now."

To reduce their living costs, she and her husband moved from the national capital, Delhi, to her hometown, Varanasi, in the neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh.

"We couldn't afford to live in Delhi. Our savings dried up. My husband is not getting paid in full either. He only gets 30% of his salary," Ms Srivastava says.

"I have been hunting for a job for seven months. Wherever I go, they tell me that I only have experience in the aviation sector. But I have a background in finance too."

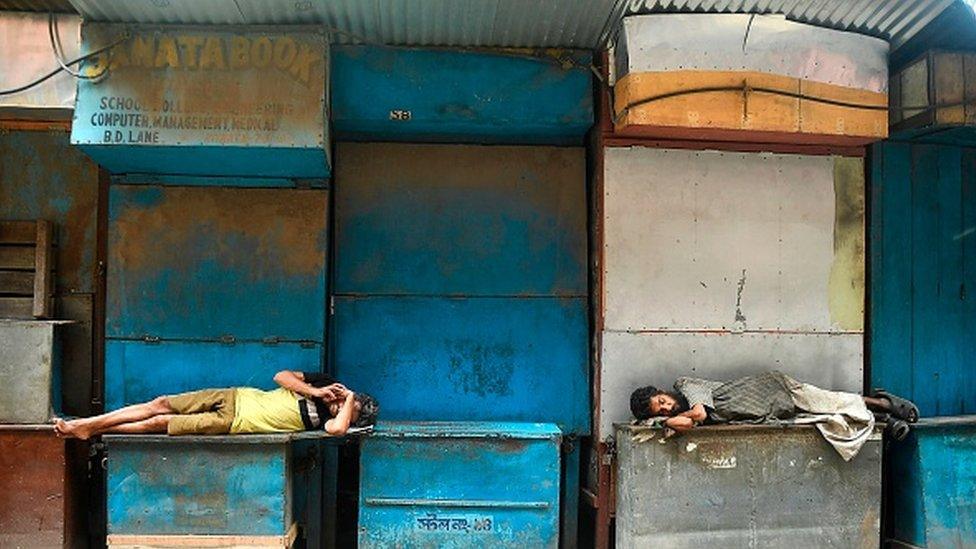

Although flights have resumed, passengers are still nervous about flying

But experts fear that the recovery, like the virus' progress, will be prolonged and full of uncertainties. For one, the pandemic's impact on the global economy and the slowdown in India will both effect aviation in the long-term. And consumer demand will likely pick up slowly.

What airlines need is cash - in the form of government-backed credit lines or loans to help them get back up and running.

Ms Jagasheth says the government could help in other ways too: "Waiver of airport parking charges or navigational services for three months could help."

But beyond that, experts say, it's a waiting game.

"Demand is improving but it's still significantly lower," Mr Kaul of CAPA - Centre for Aviation says. "There are no visible trends that key traffic segments like business or leisure are returning soon and there are no expansions likely until the end of the financial year 2022 by key players."

- Published2 September 2020

- Published27 January 2020