Savarkar and Gandhi: Why Indians are debating a mercy plea from 1911

- Published

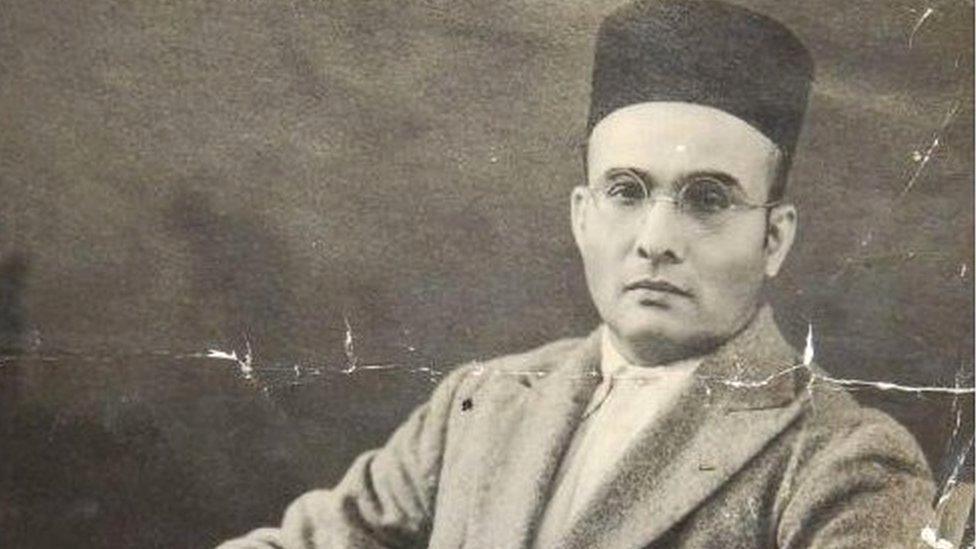

Savarkar remains a polarising figure, more than five decades after his death

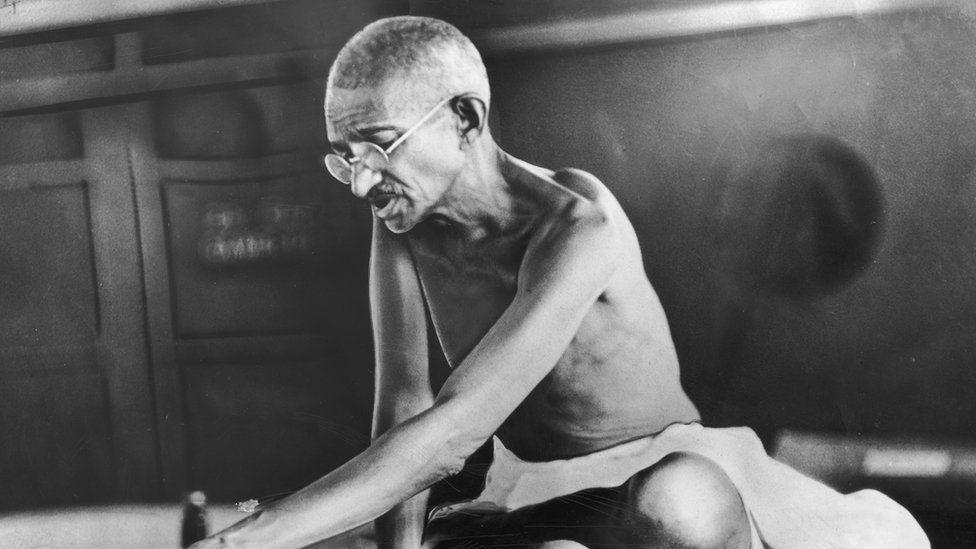

Did one of India's most divisive political figures repeatedly seek a pardon from the British authorities while in prison? And did his ideological foe and independence hero Mahatma Gandhi support his plea for amnesty?

More than five decades after his death, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar's legacy remains fiercely contested.

Although the right-wing leader was exonerated of all charges, his critics allege that Savarkar was connected to the 1948 assassination of Gandhi. They dispute his role in the Indian freedom struggle and condemn his advocacy of a "Hindu nation".

Savarkar's supporters believe that the leader - who later led the Hindu Mahasabha party and birthed the idea of Hindutva or Hindu-ness - was a staunch nationalist and an unwavering patriot.

Earlier this week, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, a key functionary of the Hindu nationalist BJP government, waded into the controversy.

He said among the "many falsehoods" about Savarkar was that "he filed multiple mercy petitions before the British government". Mr Singh, according to reports, external, insisted that Savarkar "did not file these petitions for his release", adding that Gandhi had asked him to file a plea for mercy.

Mr Singh's remarks sparked protests from Savarkar's critics. Gandhi, an ardent pacifist and opponent of the revolutionary, could not have advised and supported Savarkar's release, they said. One opposition leader blamed, external Mr Singh for "trying to twist history".

Biographers of Savarkar believe the truth is more nuanced.

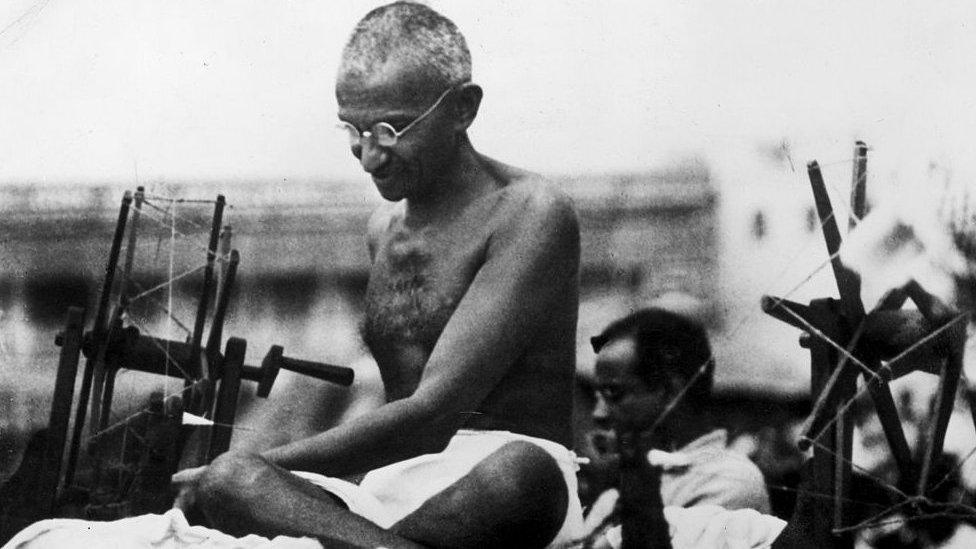

For one, Savarkar did write at least seven petitions between 1911 and 1920 for his release from the notorious Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands, where he and his brother Ganesh spent 10 years after they were sentenced for life for waging a war against the state.

The pleas followed a royal proclamation giving amnesty to political prisoners in India. However, British officials - one of them believed that Savarkar was "one of the most dangerous men that India has produced" - rejected the appeals.

One reason for these frantic petitions may well have been Savarkar's ailing health due to the abominable living conditions in the prison, his biographers say. In a 1920 petition, he expressed his "willingness to join the constitutional line of political activity and abstain from political activity for a long period of time", notes Vikram Sampath, historian and author of a two-volume biography of Savarkar.

Critics have mocked Savarkar over the petitions, alleging he apologised to the British rulers to get out of prison. They also say that the leader concealed the fact that he wrote them.

Some of his own supporters insist that Savarkar never wrote such petitions, and even if he did, he certainly did not seek clemency from the British. "Both the allegations are untrue. Savarkar wrote petitions for clemency himself and never denied writing them," says Vaibhav Purandare, author of another recent biography of the leader.

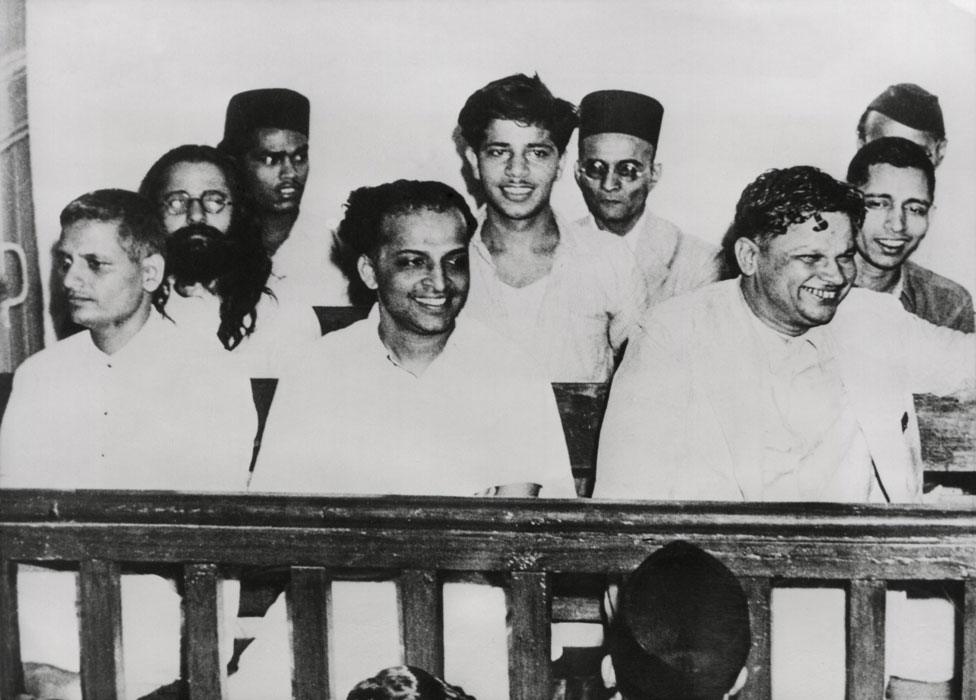

Savarkar (third row, second from left) along with the co-accused during the Gandhi murder trial

But did Gandhi guide Savarkar to seek a pardon?

The two were fiercely opposed to each other. Historian Ramachandra Guha says Savarkar's rivalry with Gandhi dated back to 1909 when "he openly abused Gandhi".

"His hatred of Gandhi was [also] intensely personal," Dr Guha said.

When the leader's wife, Kasturba, died, Savarkar refused to contribute to a fund being created in her memory, saying that "Gandhi had never shed a tear for the martyred men and women hung and shot by the British in pursuit of their armed attempts to overthrow British rule," Dr Guha noted.

Yet, in January 1920, Savarkar's younger brother Narayan Rao "did the unthinkable" by writing a letter to Gandhi, a man ideologically opposed to his brother, writes Dr Sampath.

"In the first of six letters he sought the latter's help and advice in securing the release of his elder brother in the wake of the royal proclamation."

Gandhi sent a rather anodyne reply a week later.

He wrote: "It is difficult to advise you. I suggest, however, framing a brief petition setting forth facts of the case bringing out in clear relief the fact that the offence committed by your brother was purely political."

However, a few months later, Gandhi "built a case for their release" in an article in Young India, a weekly paper. He wrote that the Savarkar brothers had said "they did not entertain any revolutionary ideas".

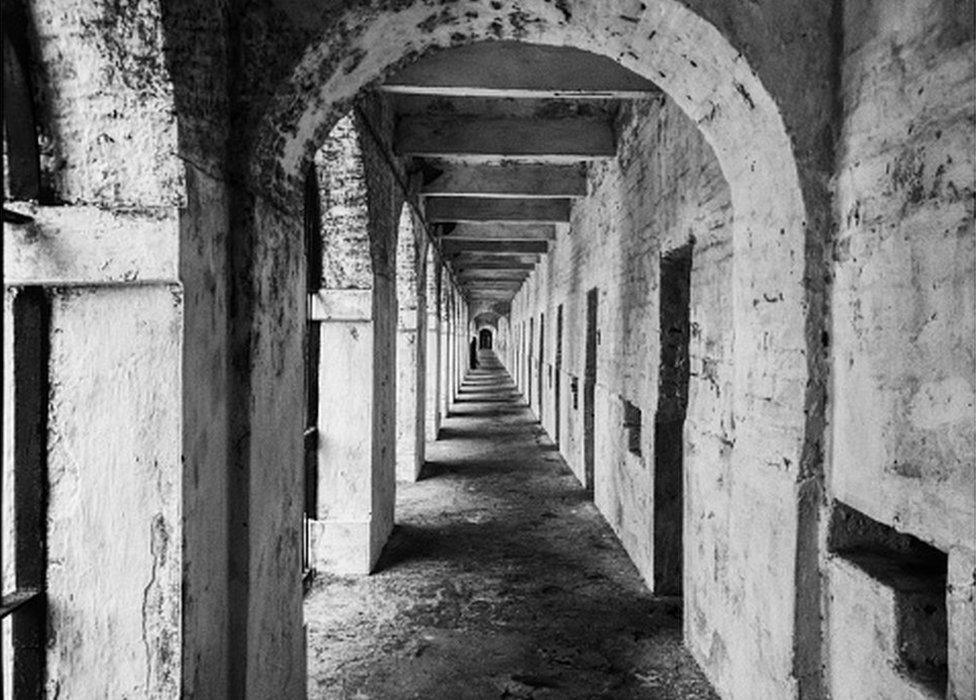

Savarkar was incarcerated in the notorious Cellular Jail in the Andaman islands

"They both state unequivocally that they do not desire independence from the British connection. On the contrary, they feel that India's destiny can be worked out in association with the British. Nobody has questioned their honour or their honesty," Gandhi wrote.

Clearly, Gandhi's "intervention" in the affair happened after Savarkar had already begun filing his pleas - in fact he was not even in India when the first such plea was filed.

His biographers believe that writing these petitions did not amount to "cowardice," as many of Savarkar's critics allege. "By writing these petitions, Savarkar was availing of his rights as a political prisoner at that time. In my opinion, the petitions do not make him less of a revolutionary or an apologist for British rule," says Mr Purandare.

The latest brouhaha may have been needless, Dr Sampath says. But it underlines how Savarkar remains a polarising figure, revered by his supporters and loathed by his critics.

Savarkar was also a man of contradictions. On the one hand he was an outspoken political voice for the Hindus. On the other, he was a rationalist, who opposed Hindu superstition, the caste system, and worship of the cow - a sacred animal for the Hindus. But after he was charged as a co-conspirator in Gandhi's killing, Savarkar became politically "untouchable".

He spent nearly a third of his life in some form of confinement - jails and restricted movement - before he died, aged 83, in 1966. "He was a bundle of contradictions and a historian's enigma," writes Dr Sampath.

Under the BJP, Savarkar's views have seen a robust revival. The RSS, the BJP's ideological fountainhead, is deeply influenced by the leader. Hindutva is the cornerstone of BJP's ideology.

"He's always evoked extreme reactions. From a political revolutionary he became an untouchable and now his legacy is on the ascendant," says Mr Purandare. But it is a legacy deeply mired in controversy and contradiction.

Related topics

- Published30 January 2017