The Indian 'germ murder' that gripped the world

- Published

This grainy portrait is possibly the only publicly available picture of Amarendra Pandey

On the afternoon of 26 November 1933, a diminutive man brushed past a young landlord in a crowded railway station in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata (then Calcutta).

Amarendra Chandra Pandey, 20, felt a jab of pain in his right arm as the man dressed in khadi, or coarse, homespun cotton, disappeared into the crowd at Howrah station.

"Someone has pricked me," he exclaimed, but he decided to press on with his journey to the family estate in Pakur, a district now in neighbouring Jharkhand state.

Accompanying relatives implored Amarendra to stay back and get his blood tested. But his half-brother Benoyendra, who was 10 years older and had arrived at the station uninvited, "made light of the incident" and persuaded him not to delay.

Three days later, a doctor examined Amarendra - he had returned to Kolkata after contracting a fever - and saw "something like the mark of a hypodermic needle" at the place where he had felt the prick. Over the next few days, the patient developed a high fever, swelling in his armpits and early signs of lung disease. On the night of 3 December, he sank into a coma. He died early next morning.

Doctors certified that Amarendra had died of pneumonia. But lab reports that arrived after his death pointed to the presence of Yersinia pestis, the lethal bacteria that causes plague, in his blood.

Transmitted by rodents and fleas, plague killed more than 12 million people in the Indian subcontinent between 1896 and 1918. Plague deaths had fallen to around half-a-million between 1929 and 1938, and there had not been a single case of plague recorded in Kolkata in the three years up to Amarendra's death.

The murder took place in the busy Howrah station in Kolkata (then Calcutta)

The sensational killing of the scion of a wealthy zamindar (landlord) family gripped people in British India and beyond. It was described by some as "one of the first cases of individual bioterrorism in modern world history".

Publications followed the story closely. Time magazine called it a "murder with germs", while Singapore's Straits Times described it as the "punctured arm mystery".

Investigations by the Kolkata police unveiled a tangled web of conspiracy and a stubbornly audacious plot, involving purloining deadly bacteria from a hospital in Mumbai (then Bombay), some 1,900km (1,100 miles) away.

At the heart of the crime was sibling rivalry over family spoils.

The Pandey half-brothers had been engaged in a bitter two-year battle over their deceased father's sprawling estate in Pakur, an area well known for its coal mines and stone quarries. The story of the feuding brothers was framed in popular media reports as one between good and evil.

Amarendra, according to one account, was a "gentlemanly, upholder of high ethical and moral standards, keen on pursuing a higher education, with a penchant for a regular fitness regime" and "much loved" among the locals. Benoyendra, on the other hand, "led a dissolute life, excessively fond of drinking and women".

According to court documents, the plot to kill Amarendra was possibly hatched in 1932 when Taranath Bhattacharya, a doctor and close friend of Benoyendra, unsuccessfully tried to source a culture of plague bacteria from medical laboratories.

Although disputed, some accounts suggest Benoyendra may have first tried to kill his half-brother in the summer of 1932. The two had gone for a walk in a hill station when Benoyendra, according to a report by British health official DP Lambert, "produced a pair of spectacles and forcibly squeezed them on Amarendra's nose, breaking the skin".

Amarendra soon fell sick - the suspicion apparently was that the glasses were tainted with germs. He was diagnosed with tetanus, and given anti-tetanus serum. Benoyendra allegedly brought in three doctors to try change his brother's treatment, but all of them were refused, according to Dr Lambert's account.

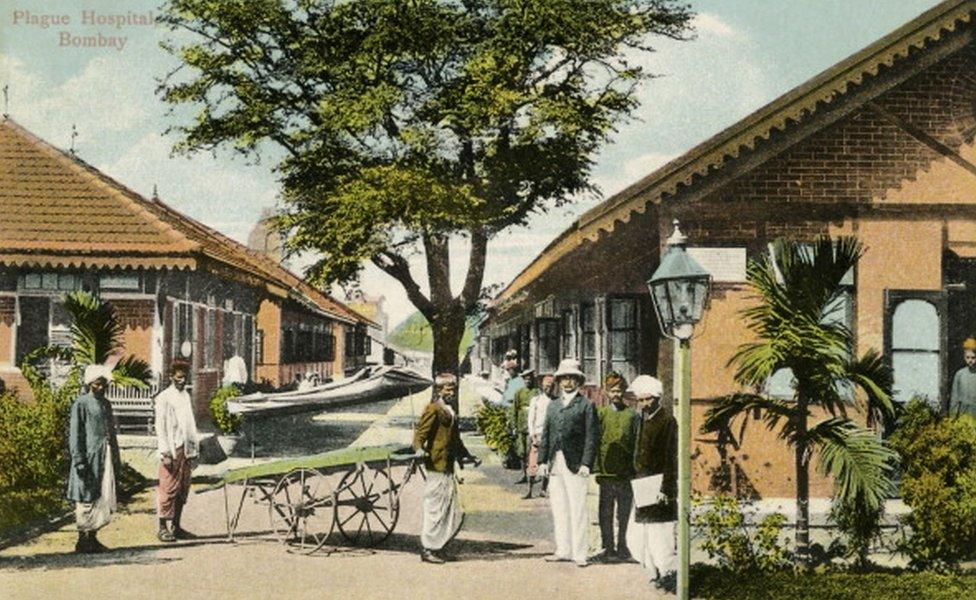

Plague killed more than 12 million people in the Indian subcontinent between 1896 and 1918

What happened over the next year was a plot which was ahead of its time.

As Benoyendra moved to gain possession of the estate, his doctor friend Bhattacharya made at least four attempts to obtain a culture of plague bacteria.

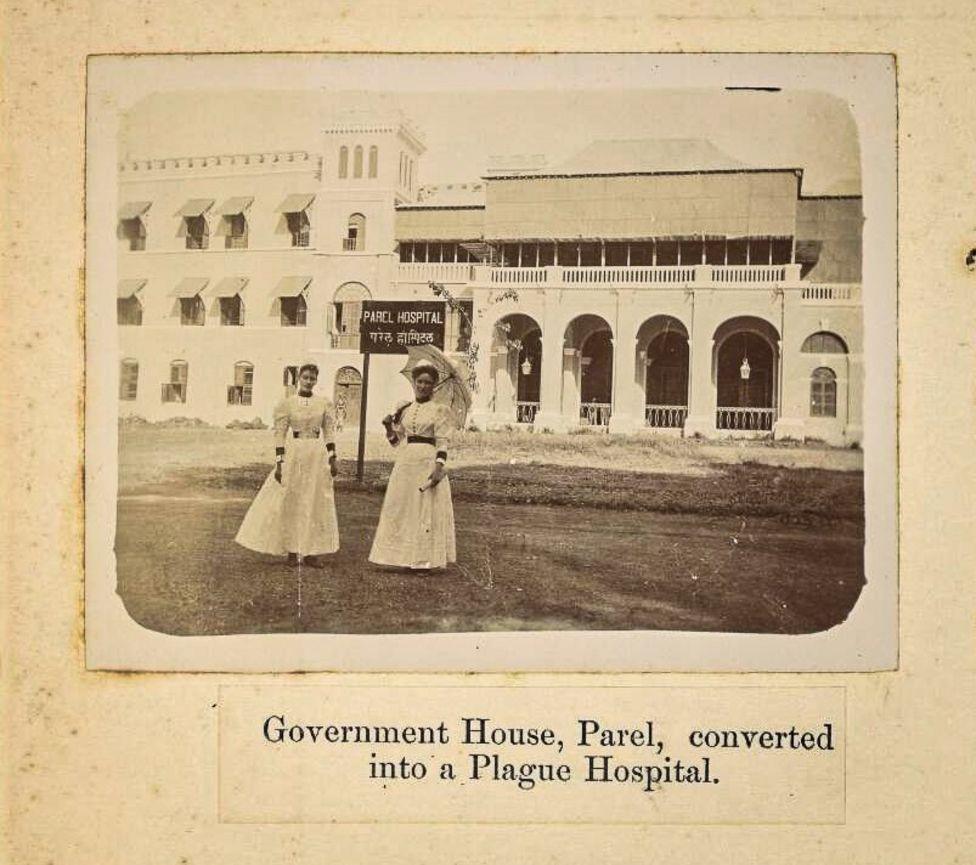

In May 1932, Bhattacharya contacted the director of Mumbai's (then Bombay) Haffkine Institute, the only laboratory in India where these cultures were kept. The director of the lab refused to supply any unless he had the permission of the Surgeon-General of Bengal.

The same month, Bhattacharya approached a doctor in Kolkata and claimed he had discovered a cure for plague, and that he wished to test it, using a culture. According to court records, the doctor allowed him to work in the lab but prohibited him from handling a culture obtained from Haffkine Institute. The work came to a halt as the bacteria failed to grow in the culture, according to Dr Lambert.

In 1933, Bhattacharya again coaxed the doctor in Kolkata to write a letter to the director of the Haffkine Institute. In it the doctor sought permission for Bhattacharya to use the institute's facilities to test his "cure for plague".

That summer, Benoyendra travelled to Mumbai. There he joined Bhattacharya and tried to bribe two veterinary surgeons attached to the institute to smuggle out a culture of plague bacteria.

Benoyendra also went to a market and bought rats to help them pass themselves off as serious scientists. Then the two men went to the Arthur Road Infectious Diseases Hospital, which also stored cultures.

There Benoyendra persuaded officials to "allow his doctor friend to work in his laboratory on his alleged cure", court documents show. There was no evidence that Bhattacharya did any experiments in the lab. On the evening of 12 July, some five days after being given access to the laboratory, Bhattacharya abruptly cut short his "work" and returned to Kolkata with Benoyendra.

Attempts were made to steal bacteria cultures from the Haffkine lab in Mumbai (then Bombay)

The police arrested the two men in February 1934, some three months after the murder. Investigators tracked down Benoyendra's travel papers, his hotel bills in Mumbai, his handwritten entries in a hotel register, his messages to the lab, and receipts from the shop from where he purchased the rats.

By all accounts, the nine-month-long trial was riveting. The defence argued that Amarendra had been bitten by a rat flea. The court said the evidence proved that the two men accused of his murder had "stolen plague bacilli" from the Mumbai hospital and that "they could be carried to Calcutta and kept alive till 26th November 1933", the day of the murder.

The trial court found Benoyendra and Bhattacharya had conspired to kill Amarendra with a "hired assassin", and sentenced them to death. In January 1936, the Calcutta High Court, on appeal, commuted the sentences to life. Two other doctors who were arrested in connection with the murder were acquitted because of lack of evidence. "The case is probably unique in the annals of crime," a judge who heard the appeal remarked.

Dan Morrison, an American journalist who's researching a book on the killing called The Prince and the Poisoner, told me that Benoyendra was a "20th Century man who thought he would outsmart the Victorian institutions that dominated India at the time of the murder". The railway station killing, according to Mr Morrison, was a "thoroughly modern murder".

Biological weapons have been used possibly since the 6th Century BC when the Assyrians poisoned enemy wells with rye ergot, a fungal disease. But, in many ways, Amarendra's murder has echoes of the killing of Kim Jong-nam, the 45-year-old half brother of North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un, as he waited for a flight in Kuala Lumpur in 2017. Two women, who were later arrested, had rubbed his face with a lethal nerve agent.

In the case of the almost-forgotten Howrah railway station murder 88 years ago, the man who murdered the prince and the weapon of killing - the hypodermic needle - were never found.

Read more by Soutik Biswas