Why some Indians die younger than others

- Published

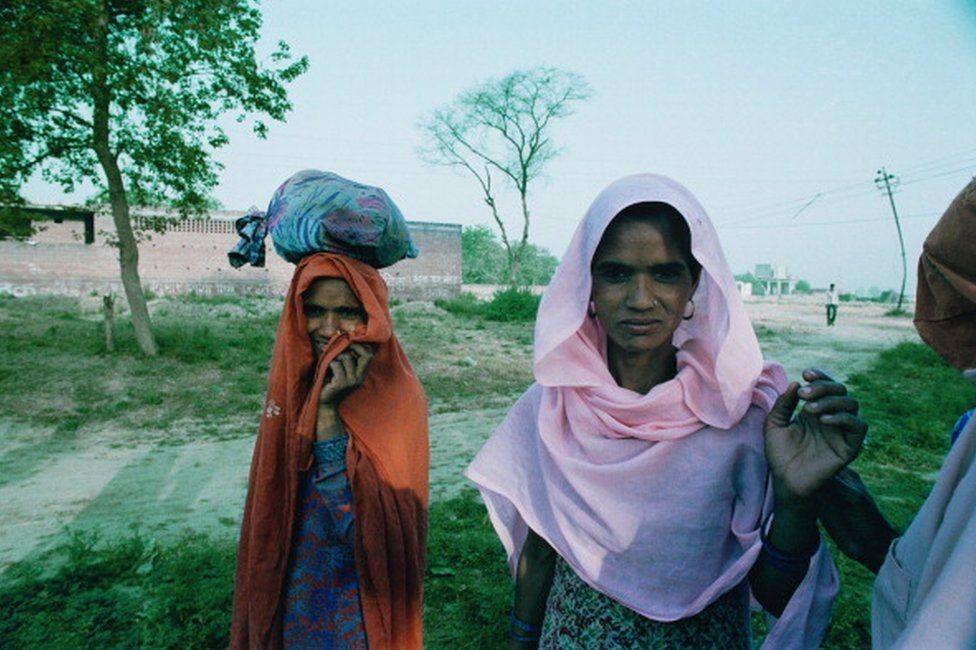

India's 230 million Dalits, despite political and social empowerment, continue to face discrimination

A new-born Indian can expect to live for 69 years, just three years short of the world average.

But disparities in life expectancy - the average number of years that a person can expect to live - among India's social groups have lingered and widened, according to two new studies.

People belonging to the country's most marginalised social groups - adivasis or indigenous people, Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) and Muslims - are more likely to die at younger ages than higher-caste Hindus, according to one paper, external by Sangita Vyas, Payal Hathi and Aashish Gupta.

They examined official health survey data of more than 20 million people from nine Indian states accounting for about half of India's population of 1.4 billion.

The researchers found that the expected life spans of adivasis and Dalits were four and three years shorter respectively than higher-caste Hindus. Muslims were expected to live a year less than higher-caste Hindus.

Let's now break this down further by gender.

This is how many years India's disadvantaged women are expected to live: 62.8 for adivasis, 63.3 for Dalits and 65.7 for Muslims. An average higher-caste Hindu woman is expected to live for 66.5 years.

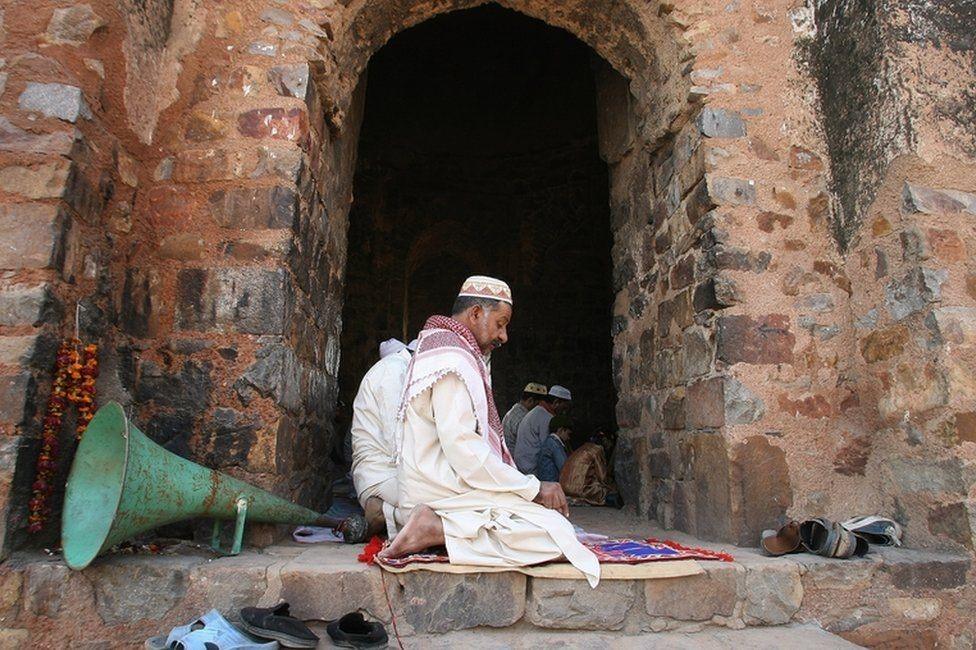

An overwhelming majority of 200 million Muslims continue to languish at the bottom of the social ladder

Here's the average lifespan of disadvantaged men: 60 years for adivasis, 61.3 for Dalits, and 63.8 for Muslims. An average higher-caste Hindu man is expected to live for 64.9 years.

Such enduring gaps were comparable in terms of years to the gaps in life expectancies between black and white Americans in the US, researchers say. Since life expectancy in India is less than four-fifths the level in the US, the outcomes in India are more substantial in percentage terms.

To be sure, buoyed by advances in medicine, hygiene and public health, India has made massive gains in life expectancy: half a century ago, the average Indian would beat the odds by surviving into his or her 50s. Now they're expected to live almost 20 years longer.

The bad news is that although life expectancy for all social groups has increased, disparities have not reduced, according to a related study, external by Aashish Gupta and Nikkil Sudharsanan.

In some cases, absolute disparities have increased: the life expectancy gap between Dalit men and upper-caste Hindu men, for example, had actually increased between the late 1990s and mid-2010s. And although Muslims had a modest life expectancy disadvantage compared to high castes in 1997-2000, this gap has grown substantially over the past 20 years.

Tribespeople account for 120 million of India's 1.4 billion population

India is home to some of the largest populations of marginalised social groups in the world. The 120 million adivasis - an "invisible and marginal minority", in the words of a historian - live in considerable poverty in some of the remotest parts. Despite political and social empowerment, the 230 million Dalits continue to face discrimination. And an overwhelming majority of 200 million Muslims, the third largest number of any country, continue to languish at the bottom of the social ladder and often become targets of sectarian violence.

What explains these gaps in life expectancy in different groups?

Here is where it gets interesting.

Researchers find that differences in where people live, their wealth and exposure to environment account for less than half of these gaps. For example, the study found that adivasis and Dalits live shorter than higher-caste Hindus across wealth categories.

To find more precise answers on how discrimination influences mortality, India needs to step up research. There is some evidence which tells us why, for example, Muslims live longer than the adivasis and Dalits. They include lower exposure to open defecation among children, lower rates of cervical cancers among women, lower consumption of alcohol and lower incidence of suicide.

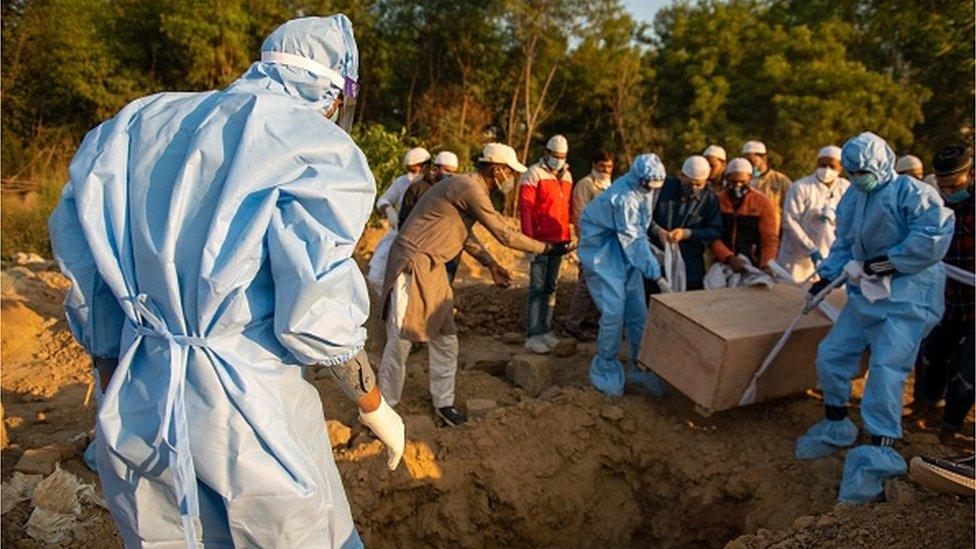

Death registration is incomplete in India

There's also evidence that the discrimination faced by marginalised groups in schools and in their interactions with government officials has deleterious impacts on physical and mental health. Such experiences have been linked to higher levels of stress-driven chronic diseases. These groups also have less access to quality health care and education, both associated with poorer health.

Marginalised groups - like sanitation workers - have greater exposure to occupations with higher risks of disease and death. The researchers say their findings suggest that health interventions that "explicitly challenge social disadvantage are essential because addressing economic inequality may not be sufficient".

Disparities between social groups are not exceptional to India: there is evidence of similar gaps in countries such as the US, Australia and UK.

But India needs much more data on causes of death to find out how discrimination impacts health. Poor record keeping means that out of an estimated 10 million deaths every year, seven million do not have a medically certified cause of death and three million fatalities are simply not registered. And as the researchers say, there's also the need to address "discrimination within health systems, as well as improve access to health for marginalised social groups".

Read more by Soutik Biswas: