Heatwave: India's poor bear the brunt of blistering temperatures

- Published

A brutal heatwave has hit India, throwing life out of gear

As a blistering heatwave sweeps through India, the country's poor are once again the most vulnerable. The BBC's Ayushi Shah reports from Mumbai city.

Sulachna Yevale, a vegetable vendor, desperately sprinkles water over her produce - some lemons and spinach that she bought from a wholesale market - to keep it from drying.

But nothing seems to help.

The extreme heat has caused some of the produce to spoil, making them useless for selling.

Even though she has been selling vegetables at the same spot for decades, Ms Yevale says this is the first time she has lost so much of her produce - worth 70 rupees (around $1; £0.80) - a significant amount for someone whose daily income is 800 rupees.

As her profits plummet, she worries about her future. She depends on the stall to provide for a family that includes her widowed daughter-in-law and granddaughter.

"I feel helpless," she says, teary-eyed.

A brutal heatwave has upended lives of millions of people in India who are struggling to cope with the soaring temperatures - the highest in over 100 years.

After record-breaking weeks, the country's weather department expects temperatures in northwest India to get slightly better, as maximum temperatures are expected to drop by 3-4C this week. But the respite is expected to be short-lived, with maximum temperatures shooting back up by 2-3C few days after that.

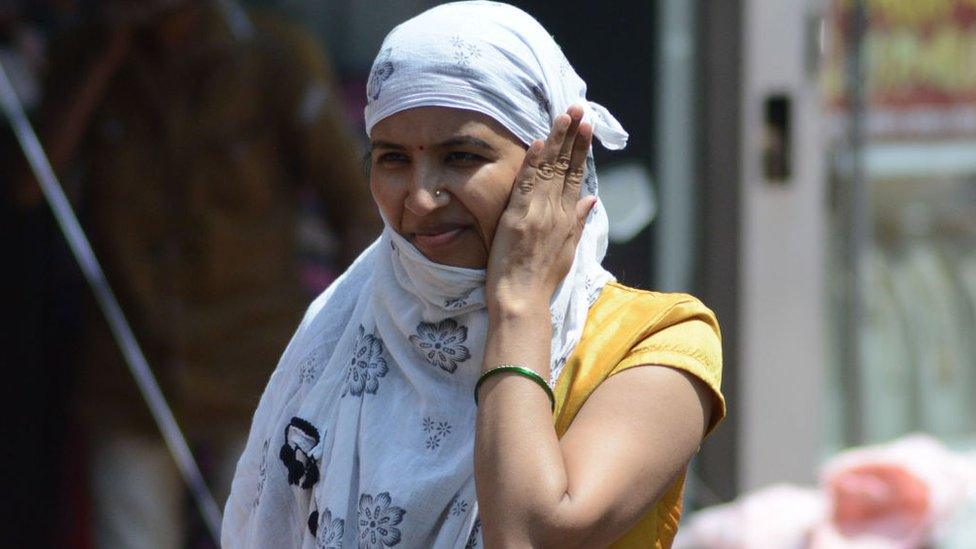

Sulachna Yevale has been a vegetable vendor for decades

Caught in the middle are India's poor - people like Ms Yevale who disproportionately bear the cost of such extreme weather events. With a limited income and little resources to adapt to the heat, they are now struggling to survive.

Prameela Walikar, a fisherwoman, wipes the sweat off her face and says that she can barely afford to keep her catch fresh in the stifling heat.

"Most of what I earn is just spent on ice trying to preserve these fish," she says. "I have never had so much spoilt fish in all these decades of selling. Now I am sometimes losing produce worth 2,000 rupees a day."

Even ice prices have risen - a twofold blow that she is struggling to adapt to.

"The government needs to provide equipment and ice to help the fishing community adapt to rising temperatures and the longer summers," she says.

Ice has become more expensive, shrinking the income of Prameela Walikar even more

The woes of the two women reflect those of millions employed in the country's vast unorganised sector, who have no choice but to work outdoors in the heat to make ends meet.

But as heatwaves become more frequent, experts say work such as construction and agriculture will become dangerous during the hottest hours of the day.

This is not just a matter of public health and safety, but also a grave economic issue for a country that is highly dependent on heat-exposed labour. India is already losing $101bn annually due to heat - the most in the world - a report by Nature Communications has found.

The lost labour hours due to increasing heat and humidity could put approximately 2.5-4.5% of GDP at risk by 2030, up to $250bn, according to a 2020 McKinsey report. The number of daylight hours - during which outdoor work is unsafe - will also increase approximately 15% by 2030, compared to a decade earlier, the report says.

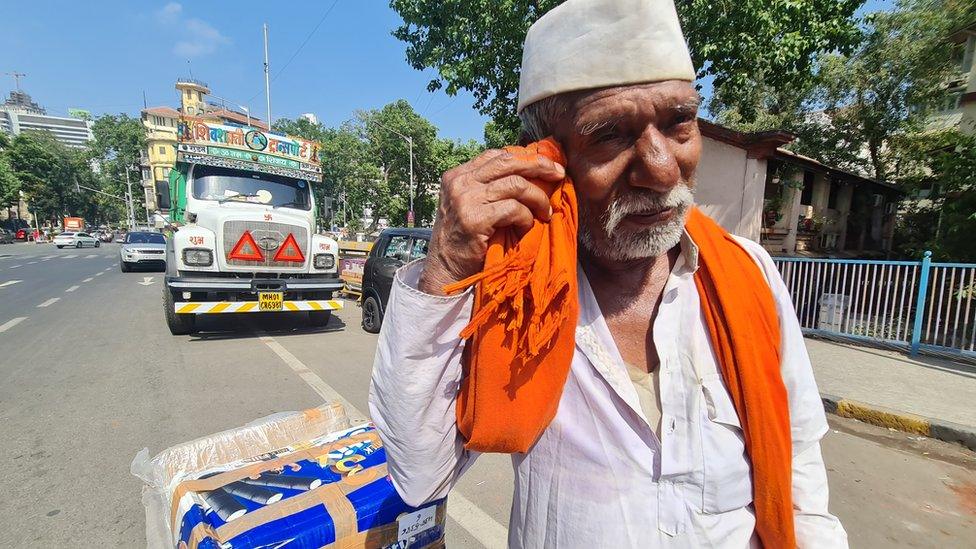

Pandurang Girhe, 76, drags his hand cart uphill on a bridge during the hottest hours of the day.

The cart weighs 60kg and feels even heavier in the scorching heat. It is a hard climb for a meagre 200 rupees, but despite his aching knees, he has little choice.

Pandurang Girhe drags his 60 kilo hand cart in the blistering heat

The heatwave that has struck India this year has been particularly severe, but experts say it is not an isolated incident - they say it is a harbinger of the type of events that might become more common in the future as temperatures rise.

But poor street vendors like Mr Girhe do not understand what heatwave means or what may have caused it. All they know is that their daily lives and their earnings are being affected, and that they must continue to work - heatwave or not - to feed their families.

"It is especially hot this year. But if I don't work, how will I fill my stomach?" Mr Girhe shrugs.

Experts say that poor infrastructure in cities has made life harder for people. Free and clean drinking water is limited and there aren't enough shelters for him to escape the heat, even for a while.

Shruti Narayan, regional director of South and West Asia of C40 Cities, says cities need to urgently take action by developing data-driven climate action plans.

"This includes clear, tangible actions on mitigation and adaptation, as well as building resilience to events we are already experiencing such as heat plans."

- Published2 May 2022