Electoral bonds: India's rocky road to transparency in political financing

- Published

Opposition parties have protested against electoral bonds

Electoral bonds were aimed at cleaning up the murky financing of India's political parties. Instead, they are being challenged in the country's top court as a "distortion of democracy".

The Supreme Court is set to resume - after two years - hearing petitions questioning electoral bonds, which are interest-free financial instruments for making donations to political parties.

Launched in 2018, these time-limited and interest-free bonds are issued in fixed denominations - 1,000 to 10 million rupees ($12.50 to $125,000) - and can be purchased from a state-owned bank during specific periods of time through the year.

Citizens and firms are allowed to buy and donate these bonds to political parties, who can cash them within 15 days. Only registered political parties who have also secured not less than 1% of the votes polled in the last election to the parliament or a state assembly are eligible to receive these bonds.

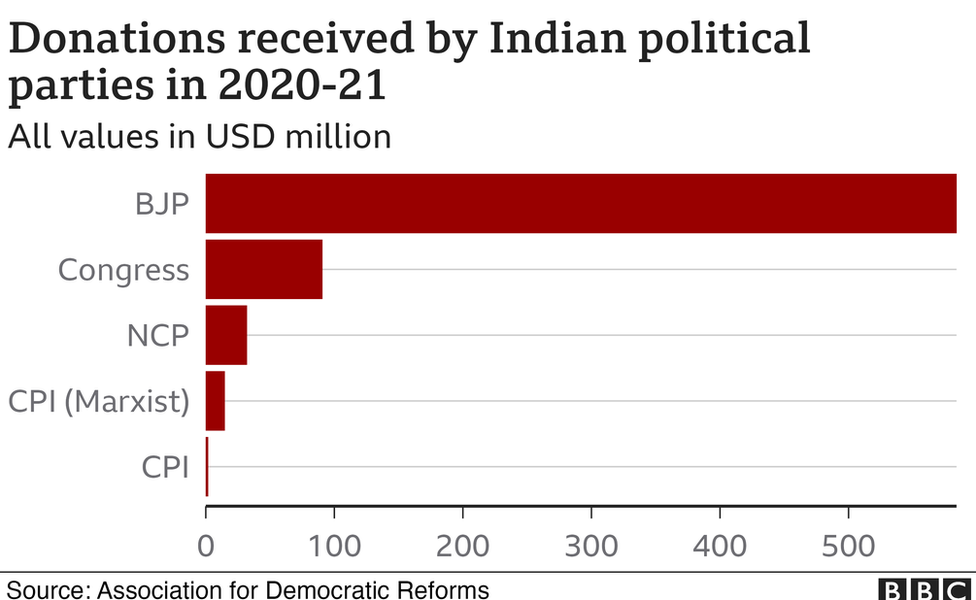

Electoral bonds worth $1.15bn have been sold in 19 tranches so far, according to the government. Prime Minister Narendra Modi's ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) appears to be the main beneficiary, external, cornering three-quarters of the bonds in 2019-20, compared with just 9% for the main opposition Congress.

More than 62% of the total income of seven national parties came from donations through electoral bonds in the same year, according to election watchdog Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR).

The bonds were introduced to flush out illicit cash and make political financing more transparent. Critics believe it has done the opposite. They say the bonds are cloaked in secrecy.

For one thing, there is no public record of who bought each bond and to whom the donation was made. That makes the bonds "unconstitutional and problematic" as taxpayers remain in the dark about the source of the donations, according to ADR.

Also, critics say, the bonds are not entirely anonymous: since the state-owned bank has a record of both the donor and the recipient, the ruling government can easily access details and "use" the information to influence donors. "The bonds give an unfair advantage to the ruling party," says Jagdeep Chhokar, co-founder of ADR.

When the bonds were first announced in 2017, India's Election Commission had said they would "compromise" electoral transparency. The central bank, the law ministry and a number of MPs had chimed in, saying the bonds would not stop illicit money being funnelled into politics. (The Election Commission flip-flopped a year later, and supported the bonds.) The courts have also deferred judgement on the bonds.

"With electoral bonds, the government has essentially legislated opacity," says Milan Vaishnav of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Washington-based think tank.

"Donors can make gifts of any size to recipients and neither side must publicly disclose the details of the transactions. If this is being advertised as 'transparency', it is truly a novel definition of the word," he adds.

The 2019 general election was estimated to cost more than $7bn

No-one is denying that India needs improved transparency in political financing. Elections are expensive and much of them are funded through private donations - the 2019 general election was estimated to have cost more than $7bn, second only to the US presidential elections.

The growing size of the electorate - more than 900 million people were eligible to vote in the 2019 polls, up from fewer than 400,000 voters in 1952 - means candidates have to spend more money reaching out to voters. The three-tier system of governance - village, state and centre - means there are more elections. Polls are also intensely competitive.

Political parties submit their income and expenditure statements to election authorities every year. Income from "unknown sources" - many say this would include the bonds - account for more than 70% of all income, according to ADR. Mr Vaishnav said that the bonds had "set the fight for campaign finance reform back by decades".

Others such as Baijayant Jay Panda, a national vice-president of the BJP, differ. Electoral bonds represent a "solid progress" towards cleaner political funding, he told me. "Earlier, almost the entirety of political funding was in suitcases of cash, sometimes from extremely unsavoury sources," he said.

Funding of political parties unquestionably needs to be legitimate, traceable and transparent, Mr Panda said. The bonds, he said, were "legitimate and achieve many of the objectives for transparency".

"While an argument can be made there should be further reforms and even more transparency, it is simply ludicrous to claim that the bonds don't represent progress and are somehow worse than what existed earlier," he added.

One way to get around this, Mr Vaishnav said, was a system where the bonds are allowed to continue but "only if accompanied by 100% transparency from all sides". This would, he believes, solve the most "egregious issues of opacity", but there are others that must also be addressed.

These include the "possibility that donors could purchase bonds with white money [money earned legally or on which tax has been paid] and sell them to a third party buying in black money [money illegally obtained or not declared for tax purposes] who then transfers the bonds to a political party," according to Mr Vaishnav.

Clearly, India's road to political finance reform is long - and tortuous.