Oppenheimer: How he was influenced by the Bhagavad Gita

- Published

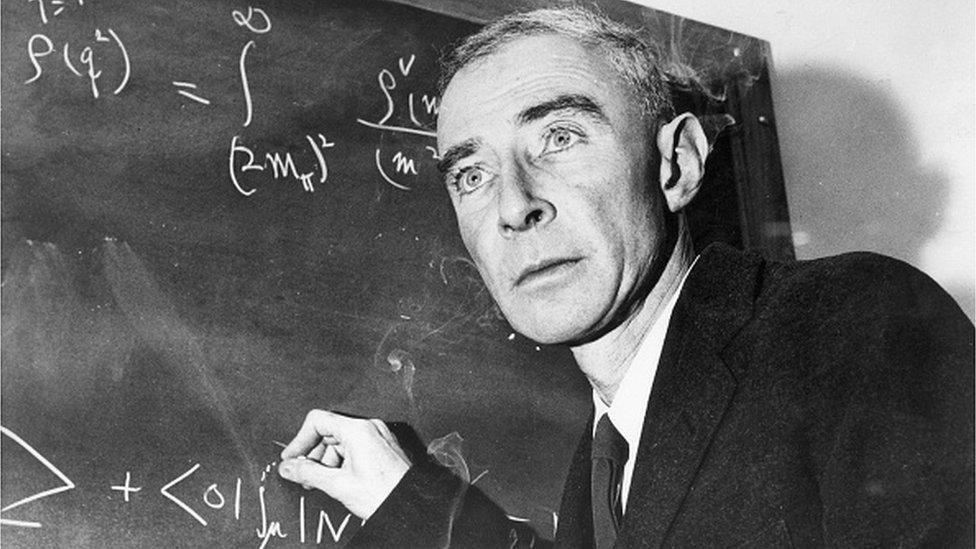

Robert Oppenheimer had a leading role in developing the atomic bomb, changing the course of World War II

Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan's sweeping new biographical thriller about the "father of the atomic bomb", has opened to a glowing reception around the world. In India, it's been a hit too but some have protested against a scene depicting the scientist reading the Bhagavad Gita, one of Hinduism's holiest books, after sex. Oppenheimer learnt the ancient Sanskrit language and counted the book as one of his favourites.

In July 1945, two days before the explosion of the first atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert, Robert Oppenheimer recited a stanza from the Bhagavad Gita, or The Lord's Song.

Oppenheimer, a theoretical physicist, had been introduced to Sanskrit, the ancient Indian language, and subsequently the Gita, as a teacher in Berkeley years before. More than 2,000-year-old, Bhagavad Gita is part of the Mahabharata - one of Hinduism's greatest epics - and at 700 verses, the world's longest poem.

Now, hours before an event that would change history, the "father of the atomic bomb" relieved his tension by reciting a stanza he had translated from Sanskrit:

In battle, in forest, at the precipice of the mountains

On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows,

In sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame,

The good deeds a man has done before defend him

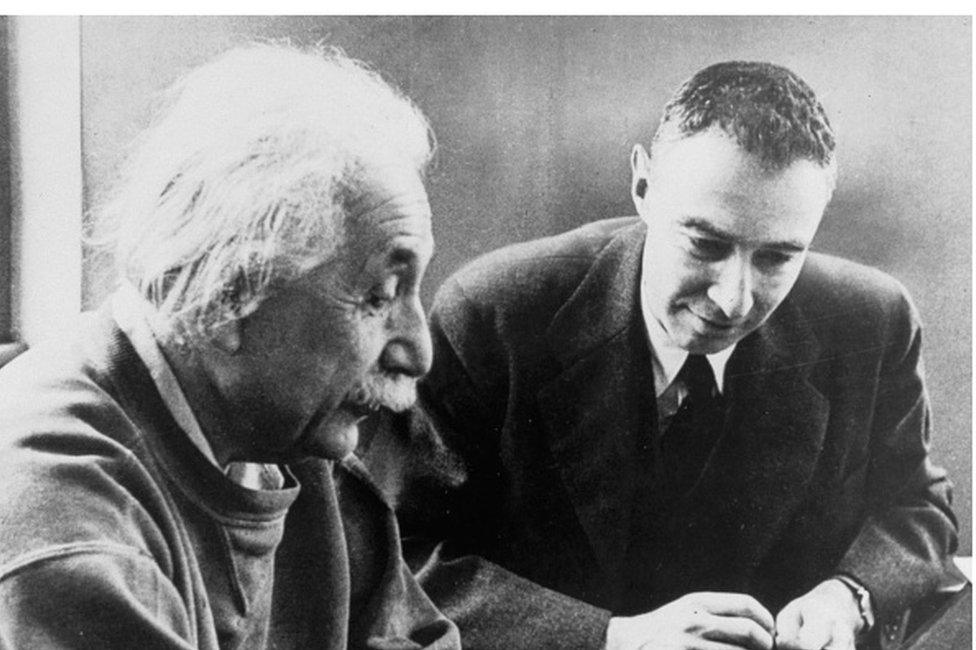

Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein in an undated picture

As Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin write in their authoritative 2005 biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J Robert Oppenheimer, a young Oppenheimer was introduced to Sanskrit by Arthur W Ryder, a professor of Sanskrit at the University of California, Berkeley. The precocious physicist had arrived there as a 25-year-old assistant professor. Over the next few decades, he helped build one of the "greatest schools of theoretical physics", external in the US.

Ryder, a Republican and a "sharp tongued iconoclast", was fascinated by Oppenheimer. For his part, Oppenheimer regarded Ryder as a "quintessential intellectual", a scholar who "felt and thought and talked as a stoic". The young scientist's textile importer father agreed, saying Ryder was a "remarkable combination of austereness through which peeps the gentlest soul".

Oppenheimer - played by actor Cillian Murphy in the biopic - also regarded Ryder as a rare person who had "a tragic sense of life, in that they attribute to human actions the completely decisive role in the difference between salvation and damnation".

Soon, Ryder was giving Oppenheimer private lessons in Sanskrit on Thursday evenings. "I am learning Sanskrit," the scientist wrote to his brother Frank, "enjoying it very much and enjoying again the sweet luxury of being taught".

Many of his friends found his new obsession with an Indian language odd, Oppenheimer's biographers noted. One of them, Harold F Cherniss, who introduced the scientist to the scholar, thought it made "perfect sense" because Oppenheimer had a "taste of the mystical and the cryptic".

So Oppenheimer's knowledge of Sanskrit and the Gita is clearly germane to telling his story. But some right wing Hindus have complained - particularly about the sex scene with lover Jean Tatlock, played by Florence Pugh - saying the film is an attack on their religion and demanding cuts.

But India's film censors found no problem with it and at the box office it's the Hollywood hit of the year in India, external, faring better than Barbie since the two blockbusters opened on Friday.

Oppenheimer (standing third, left to right) with fellow nuclear scientists near New Mexico

There's no doubt Oppenheimer was a widely well-read man - he took courses in philosophy, French literature, English, history, and briefly considered studying architecture, and even becoming a classicist, poet or painter. He wrote poems on "themes of sadness and loneliness", and identified with TS Eliot's "sparse existentialism" in The Waste Land.

"He liked things that were difficult. And since almost everything was easy for him, the things that really would attract his attention were essentially the difficult," Cherniss said.

With his facility for languages - Oppenheimer had studied Greek, Latin, French and German and learned Dutch in six weeks - it "wasn't really long before" he was reading the Bhagavad Gita. He found it "very easy and quite marvellous" and told friends that it was the "most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue". In his bookshelf was a pink-covered copy of the book that Ryder had gifted him; and Oppenheimer himself gifted copies to his friends.

The biographers write that the scientist was so "enraptured by his Sanskrit studies" that in 1933 when his father brought him a Chrysler, he named it Garuda, after the giant bird God in Hindu mythology.

In spring of that year, Oppenheimer had written a rather florid letter to his brother explaining why discipline and work had always been his guiding principles. It pointed to the fact that he was enthralled by eastern philosophy.

He wrote: "through discipline, though not through discipline alone, we can achieve serenity, and a certain small but precious measure of freedom from the accidents of incarnation… and that detachment which preserves the world it renounces". Only through discipline, he added, is it possible to "see the world without the gross distraction of personal desire, and in seeing so, accept more easily our earthly privation and its earthly horror".

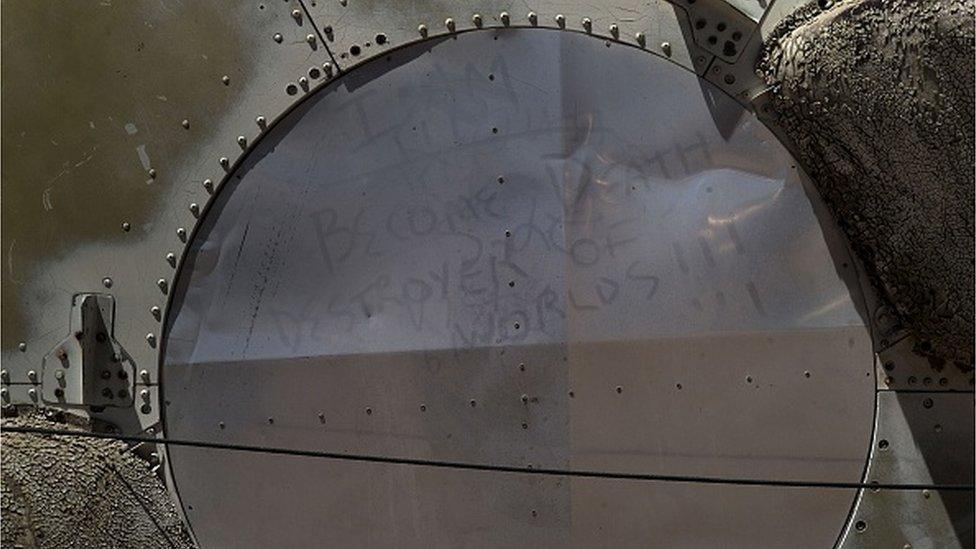

Oppenheimer quoted the Gita saying "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds" - this is seen written in dust on a deactivated nuclear missile

"In the late twenties, Oppenheimer seemed to be searching for an earthly detachment; he wished, in other words to be engaged as a scientist with the physical world, and yet detached from it," his biographers write.

"He was not seeking to escape to a purely spiritual realm. He was not seeking religion. What he sought was peace of mind. The Gita seemed to provide precisely the right philosophy for an intellectual keenly attuned to the affairs of men and the pleasures of the senses."

One of his favourite Sanskrit texts was the Meghaduta, a lyric poem written by Kalidasa, one of the greatest poets in the language. "The Meghaduta I read with Ryder, with delight, some ease and great enchantment," he wrote to his brother, Frank.

Why did Oppenheimer turn to Gita and its notions of karma, destiny and earthly duty so fervently? His biographers hazard a guess: "Perhaps the attraction Robert felt to the fatalism of the Gita was at least stimulated by a late blooming rebellion against what he had been taught as a youth", alluding to his early association with the Ethical Culture Society, an "uniquely American offshoot of Judaism that celebrated rationalism and a progressive brand of secular humanism".

To be sure, Oppenheimer was not alone in admiring the Hindu text. Henry David Thoreau wrote about immersing himself in the "stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial". Heinrich Himmler was an admirer, external. Mahatma Gandhi was an ardent follower. And WB Yeats and TS Eliot, two poets Oppenheimer admired, had read the Mahabharata.

The sight of the giant orange mushroom cloud rising in the skies after the first atomic bomb test had led Oppenheimer to return to the Gita again. The bombs that were eventually dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II had killed tens of thousands of people.

"We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent," he told NBC in a 1965 documentary.

"I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu [a principal Hindu deity] is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, "Now I have become death, the destroyer of the worlds'. I suppose we all thought that, one way or another."

A friend of the scientist said the quote sounded like one of Oppenheimer's "priestly exaggerations".

Yet, the enigmatic scientist remained profoundly influenced by it.

When the editors of The Christian Century asked the scientist once to share the books that most profoundly influenced his philosophical outlook, Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal held the top spot. And the Bhagavad Gita took the second position.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here, external to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

Related topics

- Published19 July 2023