Viewpoint: Dalai Lama's exile challenge for Tibetans

- Published

As the Tibetan parliament-in-exile meets in Dharamsala to discuss the Dalai Lama's decision to devolve his political role to an elected official, Robert Barnett of Columbia University looks at what lies behind the Tibetan spiritual leader's move.

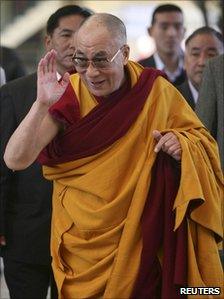

The Dalai Lama wants Tibetan exiles to confront questions about the future

The Dalai Lama's promise on 10 March to step down from his position as head of the Tibetan government has already been described by the Chinese government and his critics as "a trick".

It is true that for China and for most of us, we will not see much difference in the short term if his plan goes ahead. The Dalai Lama has said that he will continue travelling around the world as a religious leader and will still speak on Tibetan issues, albeit in a personal capacity.

So this is not a monastic vow of silence or an end to his role as the figurehead of the Tibetan people and as the most powerful voice through which their concerns will be expressed.

But the announcement is a serious matter for Tibetans. For one thing, it is about much more than retirement. The Dalai Lama, now 76 years old, declared this week not that he would retire, but that he would propose amendments to the exiles' constitution, passed by the exile parliament in 1991 and known as the "Charter of the Tibetans-in-exile", that would "devolve my formal authority to the elected leader".

At the moment, he is formally described as "the chief executive of the Tibetan government" and has the power to pass laws, summon or suspend the parliament, appoint or sack ministers, and hold referenda. In practice, he makes and confirms all major policy decisions. He is now demanding that this function, the last remaining religious feature of the Tibetan governmental system, be ended or at least reduced to a merely symbolic role.

This demand comes after decades of gradual steps by the Dalai Lama to push his followers into secular modernity. Four years after coming into exile in 1959, he had made the exiles redefine his role as akin to a constitutional monarchy with a religious leader. In 2001 he had them hold direct elections for their prime minister, a figure known as Kalon Tripa in Tibetan. This week he will attempt to get them to complete the democratisation process.

All this is partly theoretical, in that the Tibetan administration now has no state to administer and 20 years ago gave up its demands to have one. But it is not insignificant: the Dalai Lama's demand is analogous to the Pope insisting for 50 years that the Vatican State turn itself into a secular, democratic institution in which he has only a symbolic role at most.

If the exile parliament accepts the Dalai Lama's amendments at its meeting this week, it would be making an unprecedented change to centuries of Tibetan history.

Succession challenge

The statement has nothing to do with the question of who will be the next Dalai Lama, an even more serious issue - China announced four years ago that only its officials can decide which lama is allowed to reincarnate or which child is the reincarnated lama. This ensures that there will be major conflict once the current Dalai Lama dies, unless the dispute has been solved by then.

The Dalai Lama makes his announcement

But the statement does confirm who will be the official leader of the 145,000 or so Tibetans in exile: it will be the man whom the exiles will elect as their new prime minister on 20 March. The new appointee will face a daunting task - he will be a leader with no territory, no military power, no international recognition, limited revenue and an electorate riven by political, regional and religious rivalries.

There are three candidates, all of them men, fluent in English, and moderate in their politics. The leading candidate, Lobsang Sangay, has wide support because he is younger and assertive, with an academic title from a prestigious American university. But he is without experience in government, business or management, has spent only a few days in Tibet, and knows no Chinese. The other candidates, Tenzin Tethong and Tashi Wangdi, have years of experience as leading officials in the exile administration, but are seen as conservative and reticent in their approach to leadership.

None of the candidates are monks or lamas, and it will be hard for any of them to maintain a unified community in exile. They will be unknown to Tibetans inside Tibet, whose connection is to the Dalai Lama. And China insists it will consider talks only with the Dalai Lama himself, not with the exile administration, which it does not recognise. The Dalai Lama is pushing exiles to confront these challenges whilst he is still around to step in when there is a crisis.

Flawed system

Tibetans have experienced the best aspects of the Tibetan system of religious monarchy: it is extraordinarily effective in producing national unity and moral focus when it has a gifted, charismatic and forward-thinking leader. But only three of the 14 Dalai Lamas ever achieved that stature, and as a succession method the system is disastrous, since it takes nearly 20 years to find, confirm, and educate the next reincarnation. Tibet thus experienced long periods under regents who had limited authority - one of the reasons why the former Tibet was a weak state that was so easily absorbed by China 60 years ago.

Many Tibetans are thus likely to do their utmost to try to dissuade their leader from stepping down, which they understandably see as more than symbolic, even as catastrophic - probably one reason why the Dalai Lama is trying to rush the issue through his exile parliament in the next few days. This in turn magnifies the risk that Tibetans inside Tibet, hearing limited news only from attacks on the Dalai Lama in the Chinese media, might think their leader has abandoned them.

The Dalai Lama's statement thus carries a hidden but unsurprising message: he is signalling to Tibetans that the resolution to their conflict may not come in his lifetime.

If the exiles want an institution that can continue after he dies to hold China to account over its record of poor and often abusive governance in Tibet, they will need to build a system robust enough to carry out that task without him. They are being reminded that soon they will find themselves with no choice but to have to do that on their own.

Robert Barnett is the Director of the Modern Tibetan Studies Program and an Adjunct Professor at Columbia University, New York

- Published10 March 2011

- Published8 March 2011

- Published15 July 2010

- Published16 July 2010