Unlacing the 'necklace bomb'

- Published

Madeleine Pulver had to remain extremely still during the painstaking 10-hour operation

The experience of Madeleine Pulver reads like the plot of a terrifying psychological thriller.

The 18-year-old was revising for her exams in the kitchen of her family's luxury home in the well-heeled Sydney suburb of Mosman when an intruder wearing a balaclava broke into the house and placed what appeared to be a collar bomb around her neck, leaving a ransom note before fleeing.

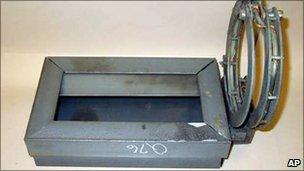

Also known as a necklace bomb, a collar bomb is essentially a device constructed to hold explosives around the victim's neck, sometimes using a collar which may be made of metal or plastic.

In the case of Madeleine, reports say, a chain attached to the device was laced around her neck.

It took bomb disposal experts 10 hours of painstaking work to disable the device and establish that it was part of what police called a "very, very elaborate hoax".

Bomb disposal experts say the collar bomb is unique in both its ability to create terror in its victim and the techniques needed to tackle it.

"If you want to inflict the most terror on a victim while leaving them in their own home, there are few things you could do more effective than putting this collar around their neck," said Roy Ramm, a former commander of specialist operations at Scotland Yard, London's police service.

'Prisoner in her own home'

The power of the collar bomb, and perhaps the reason it has resurfaced in several television series storylines, is that it represents both an extreme psychological and physical threat.

A model of the collar bomb worn by Brian Wells during a 2003 bank robbery

"It is pretty diabolical. It shows extreme callousness, even in this case when, fortunately, it turns out to be a hoax. It is a hoax that could damage the victim for the rest of their lives," said explosives engineer Sidney Alford.

"The strategic advantage of the collar bomb is extortion, because the victim is unharmed physically but money can nevertheless be demanded."

Mr Ramm agrees that collar bombs enable extortionists to create a hostage-like situation without having to worry about the practicalities of keeping a hostage alive and hidden.

"There has been a long history of the children of the rich being taken away and parents being the victims of the extortion campaign... This woman was a prisoner in her own home," he said.

The use of such devices is, experts say, extremely rare, though their nature means those few cases are inevitably high-profile.

In May 2000, a 52-year-old woman in Colombia was killed when a necklace bomb, reportedly glued to her neck, exploded. It also killed the police officer who had been trying to remove it.

The attack was blamed on left-wing guerrillas, although they accused right-wing paramilitaries of being behind it to discredit them.

In 2003, Venezuelan and Colombian police managed to disarm another collar bomb, made of a galvanised tube filled with explosives, placed around the neck of a rancher, allegedly by rebels trying to extort money.

And, in another mysterious and high-profile case in 2003, US pizza delivery man Brian Wells was killed when a collar bomb he was wearing blew up after he robbed a bank in Pennsylvania.

Different rules

Though the device around Ms Pulver's neck turned out not to be a real collar bomb, it would have been handled as such by Australian police, experts say, though they have given very few details of the operation.

"Completely different rules apply for collar bombs," said Mr Alford.

"Conventional means of dealing with an improvised explosive device would involve, for example, X-raying the bomb to know what is inside, 'sniffing' it electronically to know what it contains and then simply clearing the area and blowing it up. The latter option is simply not available when dealing with a collar bomb," he said.

It is understood that Australian police X-rayed the device to ascertain the structure of the bomb and see if it was viable, perhaps, experts say, using a pulsed X-ray to avoid harming the victim.

As such devices could be triggered remotely, by a timer, by movement or by damage to any part of the structure, in such an operation the victim would have had to stay very calm and very still.

Mr Alford said that theoretically the victim could even be put under anaesthetic to ensure they did not move.

"But they may want to talk to keep them conscious to get intelligence," Mr Alford said.

"They will be asking: 'Who was it? Did you see them adjusting what looked like a mobile telephone? Did you see them pour liquid on to a solid before they closed it? Did it click together?'," he added.

The risk to both victim and disposal experts, the media interest in such a theatrical attempt at extortion and the possibility of copycat attacks mean that what exactly happened within the rooms of the Pulver house overlooking Sydney's north shore may never be known.

- Published4 August 2011

- Published4 August 2011

- Published1 November 2010