Wild horses: Why brumbies will be culled in Queensland

- Published

A group of free-roaming feral horses in Australia or brumbies are known as a "mob" or "band"

Two fatalities in the Australian state of Queensland have prompted authorities to approve a controversial cull of feral horses on public land.

A 15-year-old boy was recently killed and his mother critically injured after the car they were travelling in collided with the carcass of a horse.

Back in July, a motorcyclist died when he hit a horse on the same highway at Bluewater, north of Townsville.

Queensland National Parks Minister Steven Miles has confirmed the long-debated cull of the brumbies will go ahead, saying it would be conducted humanely and within strict guidelines.

"We have experimented with a whole range of different options, but they have tended to result in poor animal welfare outcomes," he said.

He also asked motorists to exercise caution on the Bruce Highway, urged local residents to fix fences on their properties, and to avoid feeding feral horses.

'One horse too many'

The government estimates at least 400,000 wild horses roam the Australian continent, with the biggest populations found in the Northern Territory and Queensland.

About 200 are thought to be roaming in the Northern Beaches area around the Bruce Highway, and are increasingly wandering onto the roads.

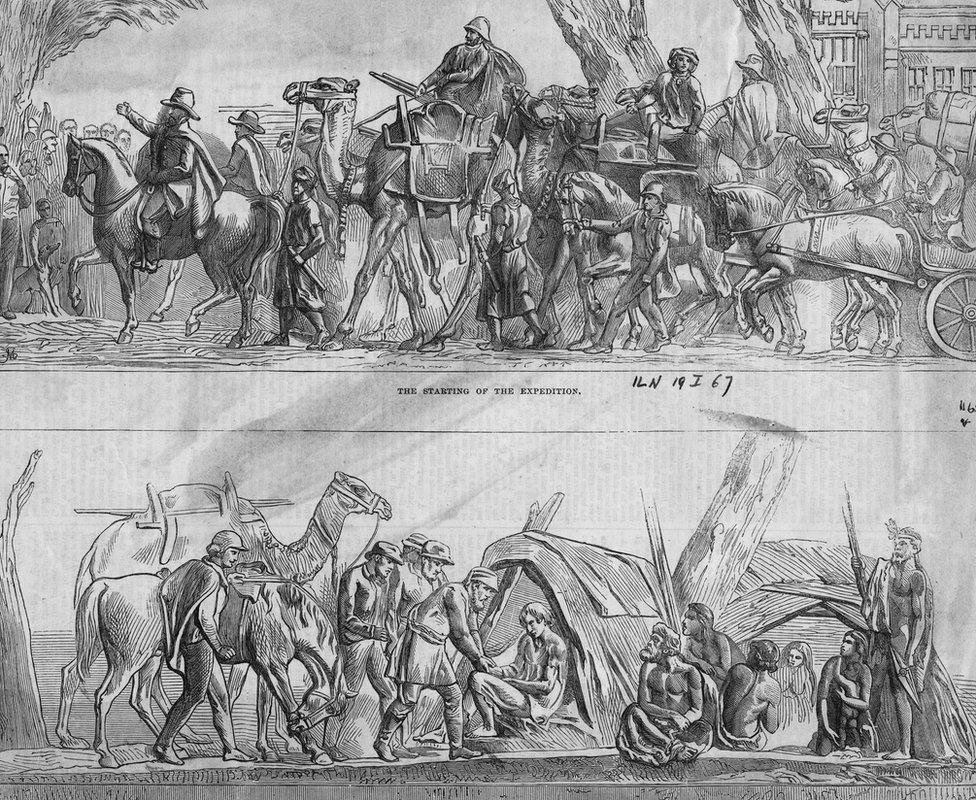

Horses arrived in Australia alongside white settlers on the First Fleet in 1788. The government says the first recorded escaped horses came about three decades later.

Former Queensland National Parks employee and Wildlife Queensland spokesperson Des Boyland said he commended the state government for taking action.

"We've been asking for a number of years," Mr Boyland said. "If there's one horse in there, there's one horse too many."

"National parks are no place for feral animals and horses are feral animals that cause economic and environmental damage."

He said the issue was controversial and politically sensitive because of the majesty and mythology surrounding the horse, immortalised in Banjo Paterson's The Man from Snowy River.

The popular poem details the mission to reclaim a prized colt living amongst the brumbies.

Australian bush poet Banjo Paterson famously wrote about the brumbies in a much-loved 1890 poem, The Man From Snowy River

Anne Wilson of the South East Queensland Brumby Association, says Australia "was built on horseback".

She told the BBC the continent was pioneered by settlers on horseback, and this is the reason horses featured prominently in the Sydney Olympics opening ceremony.

Horseriders carry Olympic flags during the opening ceremony of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney

But the horses, like many other introduced species, have since damaged native habitats and can threaten native wildlife. They can also reduce biodiversity and devalue crops.

They also compete with cattle for food and water, which the Queensland government has said, external costs the beef industry an estimated $30-60m Australian dollars ($21m: £14m) a year.

Population control

The specifics of the Queensland cull, including how and when it will be carried out, are yet to be finalised.

Aerial culling, which involves helicopters and trained marksmen, is a popular method, described by Wildlife Queensland's Des Boyland as the most humane option. But it has also been criticised as ineffective in densely forested areas.

Passive trapping is another way of controlling the populations, which is used in parts of Kosciuszko National Park in New South Wales. Brumbies are lured into trap-yards with salt and molasses, then euthanised or re-homed.

But Australian Brumby Alliance President Jill Pickering said there were alternatives.

She told the BBC road safety campaigns and signs can help manage the risks, but concedes the horse populations need to be sustainably managed.

"Numbers need to be reduced, not in my view eliminated, because they're a part of that area and many people want them there," Ms Pickering said.

"We would prefer they are then offered to people who know how to handle them, but there are very few people in the Townsville area who can do that."

- Published2 October 2015

- Published10 July 2015

- Published7 January 2015

.jpg)