How solitary broke a man named Badness

- Published

Christopher Pecotic, who is serving 14-18 years in prison for armed robbery, is largely kept in solitary confinement

As controversy rages in Norway about mass killer Anders Breivik protesting against his solitary confinement, Australia's secretive prisons are increasingly reliant on prolonged isolation, writes Matthew Thompson.

Last week, one of Australia's most notorious bandits, Christopher Dean Pecotic, was deemed stable enough after a mental breakdown to be removed from a "suicide-proofed" observation cell and returned to regular solitary.

Pecotic, better known by his nickname "Badness", had spent several weeks under suicide watch in the starkest of cells, with neither writing materials nor hanging points, in the maximum security Barwon Prison outside the city of Geelong in Victoria state. This followed the 47-year-old's collapse into despair over being held in solitary confinement for almost four years to date. He faces another decade or more of the same.

At Pecotic's lowest ebb of recent weeks, the veteran armed robber and father of a nine-year-old girl stood his mattress against the wall, and, finger-painting with his own excrement (blood and faeces being the only options), fashioned the mattress into a grave-marker. Beneath his name he scrawled a plea to any coroner investigating the death to listen to recorded jailhouse calls to his mother, conversations in which he says that he can endure isolation no longer.

Then, in his reeking cell, Pecotic tightened the fabric of his unrippable, sleeveless, canvas smock across his throat, twice choking himself into a black-out but twice spared when his grip relaxed.

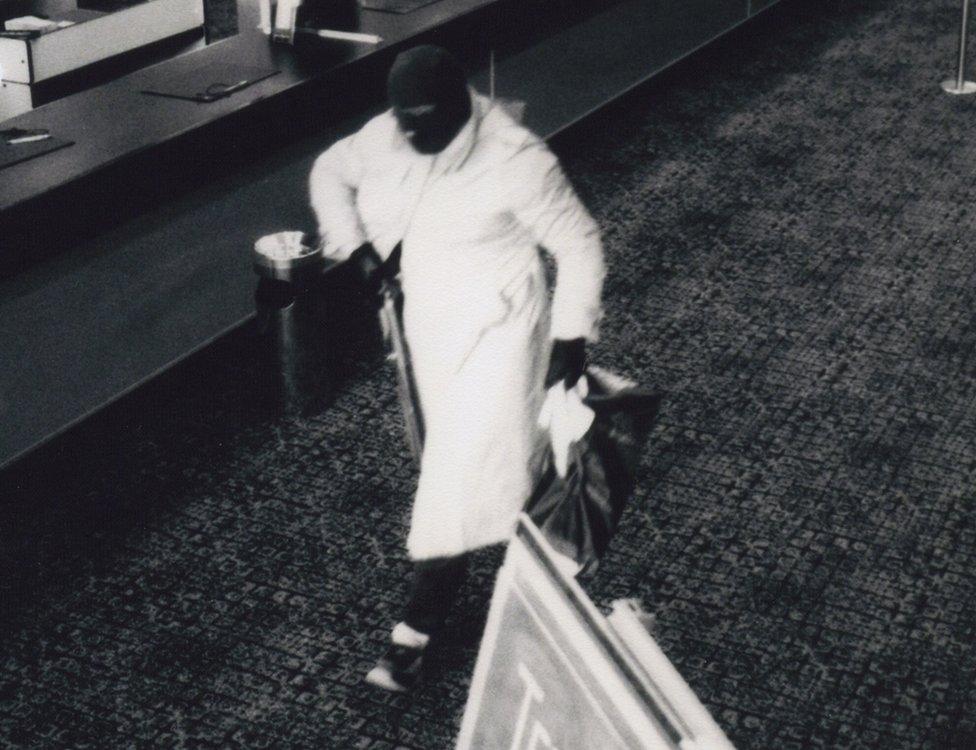

Pecotic is one of Victoria state's most notorious armed robbers

The isolation discount

In vogue with the "supermax"-style of incarceration that is popular in Australia, Pecotic is totally excluded from the company of other prisoners. He spends almost all of his time alone in an "isolation cell". For the brief periods that he is permitted to use a prison telephone or exercise equipment, guards first clear those areas of inmates.

The Supreme Court of Victoria's Justice Terry Forrest predicted Pecotic's torment when sentencing him for armed robbery, gun offences and reckless conduct endangering serious injury in 2014. The judge said the term of 14-18 years he was handing down included a discount because of the "adverse mental health" consequences likely to result from the "onerous conditions of incarceration" that Pecotic faced.

"There is a real prospect that you will be required to serve all or a large proportion of … a lengthy prison sentence in isolation cell confinement for up to 23 hours a day," Justice Forrest said when delivering the sentence.

In explaining his decision to include a discount, Justice Forrest quoted from psychiatric and psychological reports which attributed much of Pecotic's personality and behaviour to the highly restrictive conditions in which he has been held during his near-lifetime behind bars - conditions to which he was now being returned.

'Now you're lost'

Pecotic began committing crimes early in life and was a ward of the state by age 14

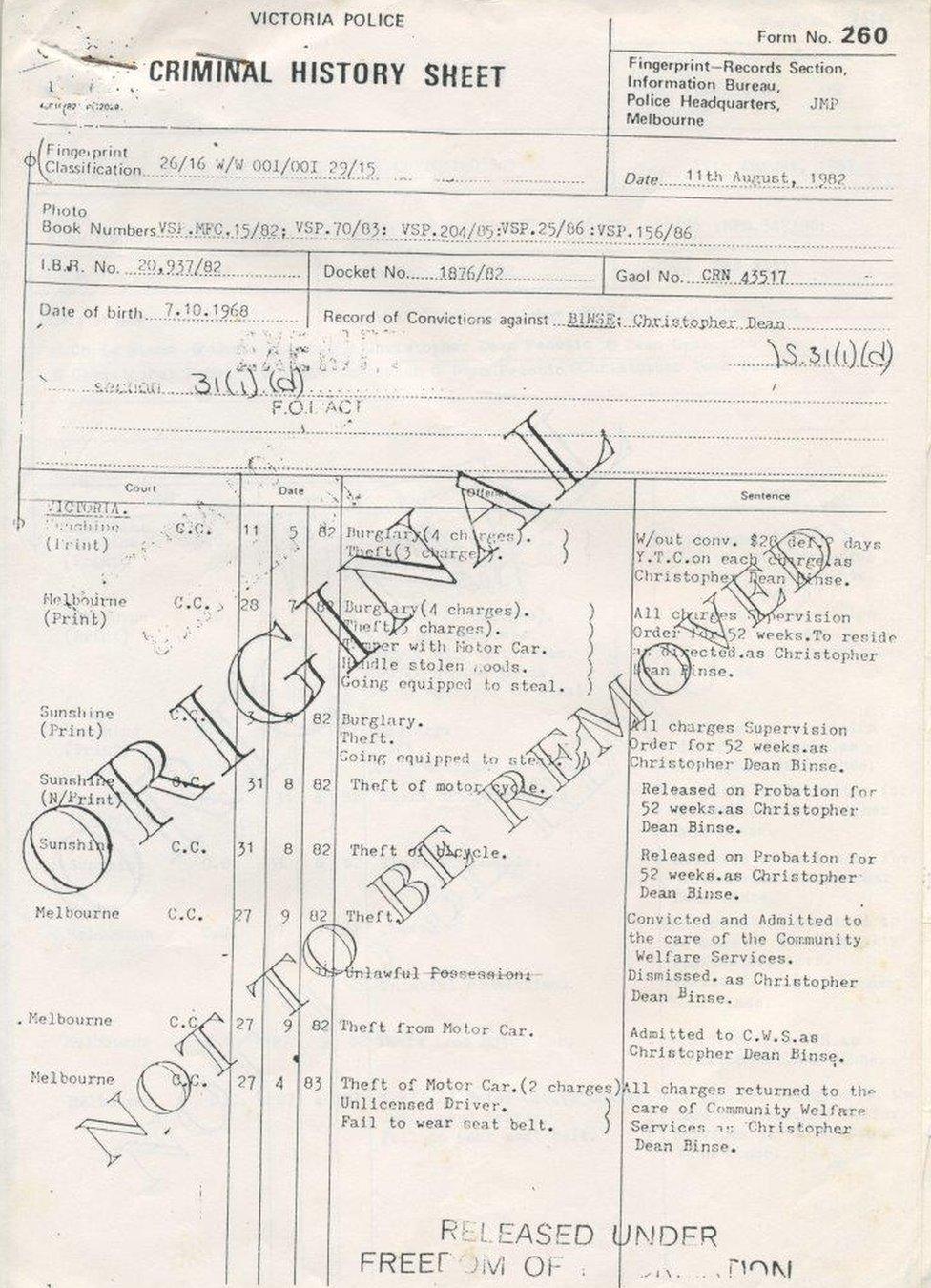

Pecotic, who is also known by his stepfather's surname Binse, came to crime early in life, egged on by his petty criminal father, Croatian immigrant Steven Pecotic. He has only been free for about four years since he was first locked up at the age of 13 and declared a ward of the state at 14.

His subsequent decades of incarceration have not been served quietly. He has feuded in the yards, been stabbed and slashed, and beaten inmates with tin cans in socks. He famously bashed Julian Knight, the shooter in Australia's Hoddle Street massacre. He has launched hunger strikes, covered himself in faeces to keep guards at bay, and had many stints in isolation.

But he has also directed his energies towards more constructive pursuits. He acted as a prison rights advocate, distributing unauthorised prisoner surveys at New South Wales' (NSW) Goulburn Prison and, after release, meeting with journalists and politicians to argue in favour of an overhaul of rehabilitation and post-release assistance programs, and against the long-term use of solitary.

In the aftermath of an early 1990s run of escapes (from Pentridge prison in Melbourne and, just weeks later, Parramatta in Sydney) and attempted escapes, Pecotic spent more than three years not only in solitary but handcuffed and shackled whenever he was outside his cell.

"There is no assimilation, no transition, nothing bridging me from an extreme environment where everything is regimented, where you're in a little yard where your mind turns to jelly," he wrote in a diary.

"You have difficulty doing just menial day-to-day stuff. You struggle because everything was done for you. Now you're lost."

Pecotic's extensive rap sheet (under his stepfather's name, Binse) from his arrest at age 13

Released into the community from isolation, he wrote: "You're a walking time bomb … The inner hate, the inner rage, is all bottled up."

'A short-term solution'

Official guidelines in Victoria say prison managers should aim to move prisoners out of solitary and return them to the main inmate population as soon as possible. Australia has also endorsed the United Nation's Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, known as the Mandela Rules, which prohibit "prolonged solitary confinement".

Such guidelines are in keeping with a wealth of expert opinion that long-term solitary confinement does profound psychological harm and works squarely against the rehabilitation of criminal offenders.

The head of Griffith University's correctional health program, Stuart Kinner, said it was "beyond dispute" that solitary confinement caused mental illness. "If anything, solitary is a short-term management solution," he said. Beyond that, it was "a way of causing a mental health problem or behavioural problem".

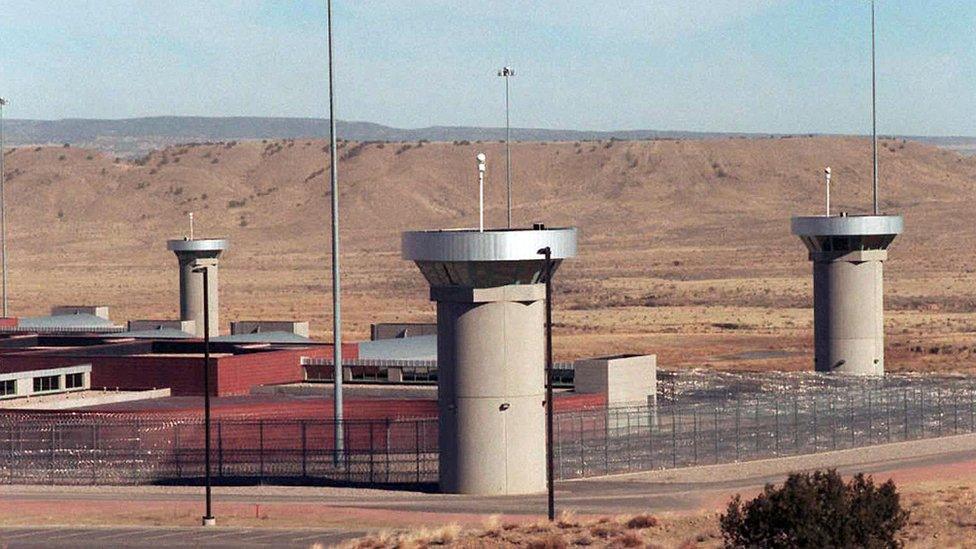

The use of supermax prisons was pioneered in the US - this facility in Colorado is dubbed the "Alcatraz of the Rockies"

The BBC put a series of questions to Corrections Victoria, including whether Pecotic's four years of isolation would end, how many prisoners were held in isolation in Victoria, how many had been held that way for a year or more and how many were released directly from isolation into the community.

In response, a spokesman issued a statement that the department was "unable to comment for operation and privacy reasons". Pecotic's circumstances were also off limits - the department "does not discuss individual prisoners".

But a 2014 report obtained under Freedom of Information laws notes that Pecotic's isolation "is not the result of a prison related incident", meaning that his behaviour during his current incarceration is not the reason for his treatment. Instead, when justifying his placement, the panel cited his past crimes and previous terms of imprisonment, noting a history of violence and risks of escape, suicide or self-harm.

Information vacuum

It is hard to know how many prisoners are in solitary, a term generally avoided in Australia. The preferred language includes "long-term management placement", "isolation cell confinement", "high-risk management", or prisoners being held in "segregated" or "protective" custody.

It must be noted that not everyone removed from the mainstream prison population is isolated from all other prisoners. Inmates such as child abusers and former police officers, who would be targets in jail's brutal pecking order, often mingle in secure enclaves.

Figures for solitary confinement and related isolation regimes are routinely absent from the plethora of prison reports issued in Australia. Fifteen years ago the NSW Judicial Commission released Protective Custody and Hardship, a report noting how little information was available about restrictive custody. From the data it could gather, the commission reported that the number of prisoners in "protection" was growing at a rate 4.4 times faster than the general prison population. The commission was not able to provide updated figures.

Mark Halsey, a professor of criminology at Flinders University, said prisons in Australia tended to inhabit a "secret world" that kept the public from knowing what is being done in its name. He said authorities should explain why Pecotic, or any prisoner jailed in such circumstances, was being kept in isolation. "In concrete, clear terms, what are the reasons that he is such a risk that he has to be kept in such a manner? That's the fundamental question," he said.

'Supermax' culture

Goulburn's supermax prison is one of Australia's most secure facilities and keeps some "high-risk" prisoners in isolated conditions

Victoria is this year scheduled to open a A$20m ($15m, £11m), 40-cell addition to Barwon's isolation facilities. When it was announced in 2014, Corrections Victoria described it as a "major boost" that would "build on the prison system's capacity to manage an increasingly complex prisoner population, including outlaw motorcycle gang members, underworld figures and violent prisoners."

"Bring it on, we need the jobs," said local councillor Tony Ansett, calling it a "good news story". But the focus on isolation at Barwon and other prisons such as the Goulburn supermax in NSW is at odds with the findings of a seminal Australian inquiry into prisons.

Established in 1977 in the wake of riots and allegations of institutionalised brutality in NSW prisons, the Nagle Royal Commission sparked numerous reforms, including the closure of Australia's first supermax, the Katingal unit inside Sydney's Long Bay prison.

Originally sold as a humane alternative to the rule of the baton in the state's older stone-walled punishment blocks where "intractable" prisoners were sent, Katingal was a high-tech panopticon, an "electronic zoo", where inmates were found to have been subject to profoundly destabilising, aggravating isolation.

Justice John Nagle concluded that not only were ultra-controlled, escape-proof prisons inhumane and enormously expensive, they also produced an alumni of individuals more embittered and deranged than when they entered. These "so-called escape free prisons", Justice Nagle wrote, offered the community "false security".

Professor Kinner of Griffith University said it was no surprise that long-term prisoners like Pecotic failed to adapt to society after their release. "That's one of the fundamental issues with the notion of incarceration: we deprive people of their liberty, we don't let them make any choices," Prof Kinner said.

"Then we send them out into a community where they're probably extremely disadvantaged. They have lots of challenges, and we tell them to make all their decisions correctly or we'll lock them up again. Doesn't sound very clever when you put it that way, does it?"

Matthew Thompson is an Australian journalist, academic and author.

- Published16 March 2016

- Published9 June 2015

- Published15 February 2014

- Published4 April 2012