Antibiotic resistance: Scientists 'unmask' superbug-shielding protein

- Published

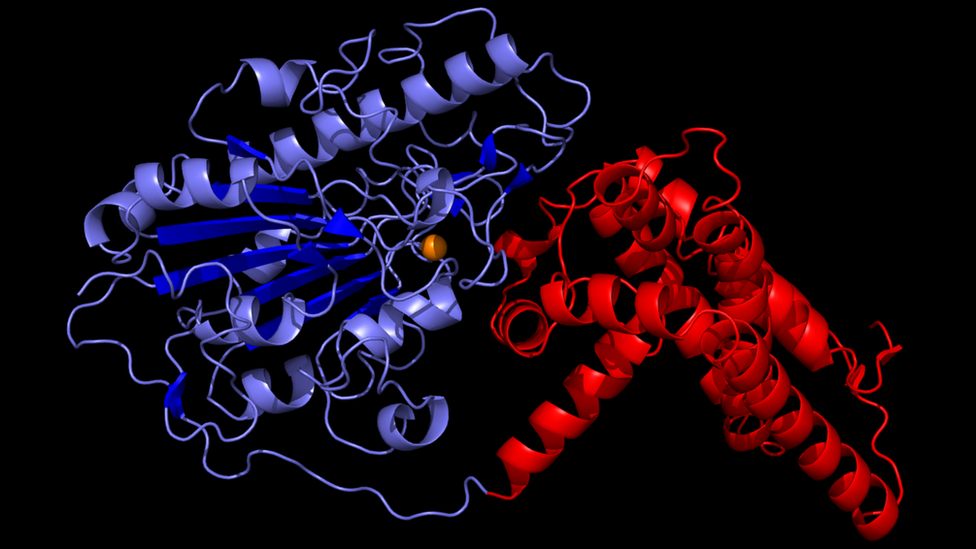

A digital representation of the EptA protein

Australian scientists have mapped the molecular structure of a protein that shields superbugs from antibiotics.

It could help develop new drugs for antibiotic-resistant bacteria strains, the University of Western Australia researchers said.

The protein, EptA, allows some strains to shrug off colistin, an antibiotic used when all other treatments fail.

It follows warnings that a so-called antibiotic apocalypse could be among the 21st Century's greatest threats.

The new research could help create treatments to inhibit the masking protein, according to lead researcher Professor Alice Vrielink.

"We can think about the protein as being like a lock of a door and it has a specific shape," said Prof Vrielink, a molecular biologist.

"If we know the three-dimensional shape, we can get an idea of what the key should look like."

Professor Alice Vrielink says the discovery can help treat superbugs

The research, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external, was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and involved several other universities and organisations.

What is the health threat?

According to the World Health Organization, drug-resistant infections kill 700,000 people each year.

One study has suggested antibiotic resistance will kill an extra 10 million people a year worldwide - more than currently die from cancer - by 2050 unless action is taken.

Scientists have identified bacteria that resist the most common antibiotic of last resort - colistin - in locations around the world. It raises the prospect of untreatable infections.

"The ability of bacteria to overcome drugs I think puts us back into a very alarming situation in terms of public health," Prof Vrielink said.

BBC Online Health Editor James Gallagher on the risks of an antibiotic-resistant 'superbug'

What's new about this research?

Using a technique called X-ray crystallography, it maps the three-dimensional structure of EptA.

"The protein provides the ability for the bacteria to cloak itself from the immune system and from antibiotics," Prof Vrielink said.

"If can stop it from doing that, we de-mask the bacteria."

What comes next?

Prof Vrielink hopes the discovery will lead to a new treatment. She said it would probably involve one drug to unmask the bacteria, and an antibiotic to treat the infection.

"A therapeutic treatment is probably years down the road," she said.

"It's a long process but this is our first step towards that work."

- Published6 November 2016

- Published18 October 2016

- Published24 November 2016

- Published4 November 2016

- Published19 November 2015