Australia church abuse: Why priests can't spill confession secrets

- Published

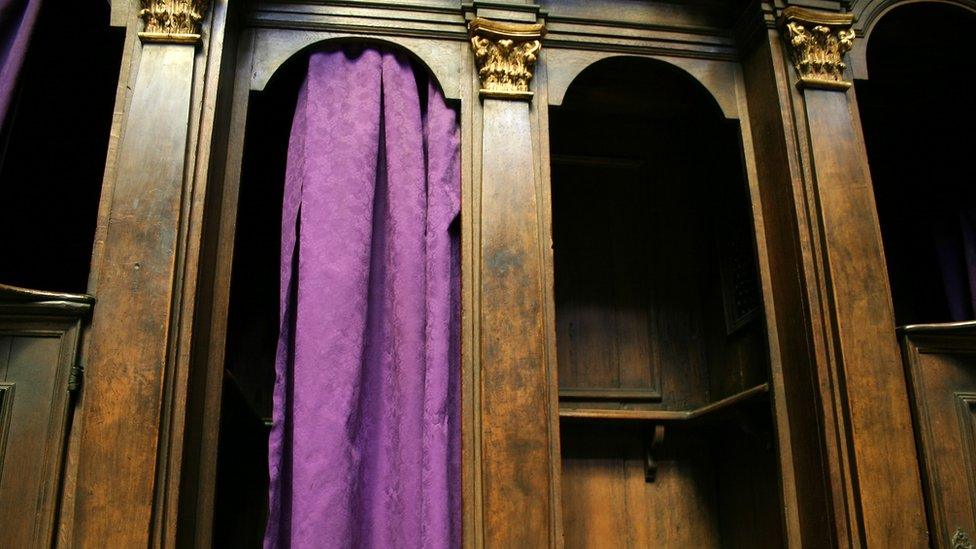

Many confessions take place through a grill to preserve the anonymity of the person confessing

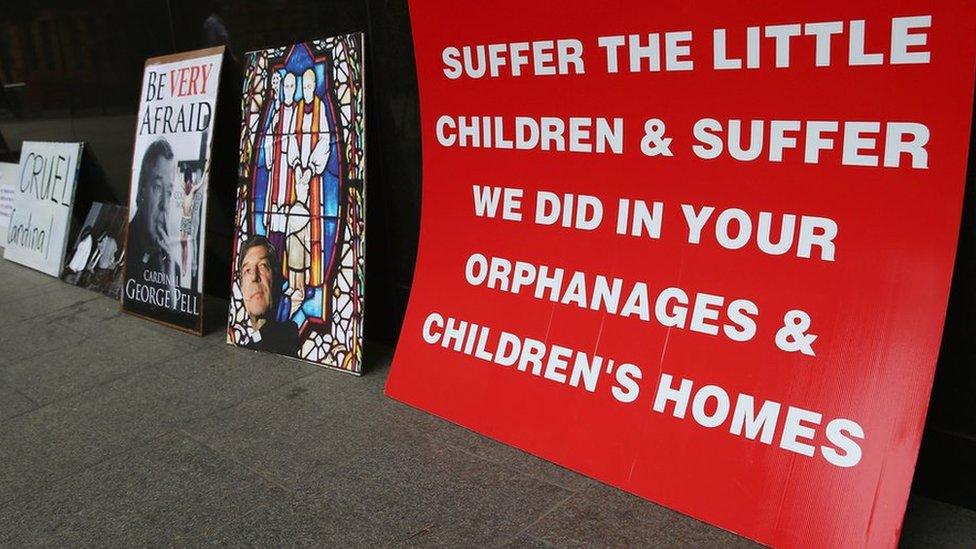

Priests who suspect child abuse after hearing confession should report it to the authorities - or face criminal charges. That is one of the conclusions reached by Australia's four-year Royal Commission investigating child sex abuse.

The proposal applies to the suspicion of child abuse in an institutional context - for example within an organisation which provides services to children or cares for them, such as a church or a children's home.

But the Roman Catholic Church in Australia is opposed to the proposal, despite saying that outside of the confession it is "absolutely committed" to reporting all offences against children to the authorities.

So what is different about confession?

Surely priests would have a moral duty - if not a legal one - to report any concerns, in order to protect children?

Archbishop Mark Coleridge of Brisbane appeared to recognise that it can be hard for non-Catholics to understand why this is not the case:

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The answer lies in the special status of confession in the Roman Catholic Church. Officially known as the Sacrament of Penance, it is one of the seven sacraments of the Church.

The penitent (person wishing to confess) talks to the priest or bishop, beginning with the words: "Forgive me Father, for I have sinned."

Catholics believe that within the confessional the penitent is talking to God, with the priest serving as an intermediary. The priest is able to absolve the person of their sins.

But, crucially, everything which takes place within the confession is secret. This is known as the Seal of the Confessional.

What happens if a priest breaks the seal?

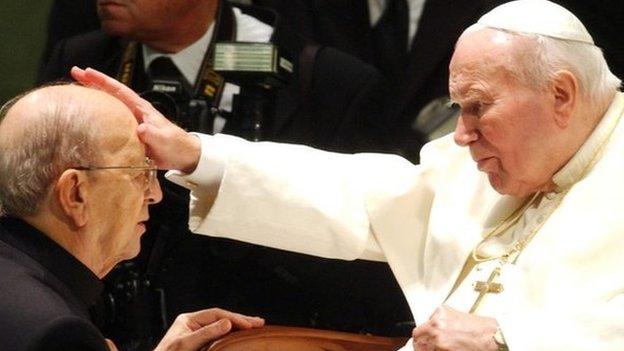

Under the law of the Church, external, if a priest breaks the seal, he is automatically punished with excommunication (being expelled from the Church). That is the ultimate sanction for a priest, and in this case can only be reversed by the Pope himself.

Confessors are not even allowed to reveal whether someone has been to confession, let alone what they said.

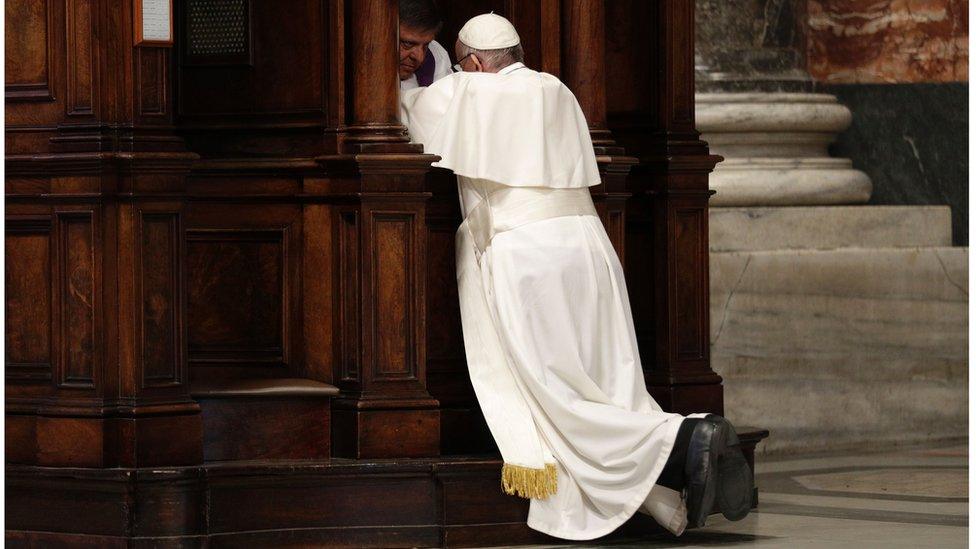

Even Pope Francis (right) has to make confession

Prohibitions on breaking the seal of confession have existed since at least 1215.

Priests have said they would be prepared to go to prison rather than break the seal of the confession.

What are people saying about this?

Earlier this year Australian child abuse survivor Peter Gogarty told the BBC that he believed the Catholic Church should reform its laws on confession to ensure crimes are reported to police.

But Mr Gogarty said he was not in favour of priests being made to report abuse to the police. "I think it would be a tragedy if the privileged communication in the confessional is abolished," he said at the time.

However, Australia's Royal Commission says there should be no exemption for confession.

The commission says it heard evidence of instances of both victims and perpetrators having discussed abuse during confession.

"We are satisfied that confession is a forum where Catholic children have disclosed their sexual abuse and where clergy have disclosed their abusive behaviour in order to deal with their own guilt," the report says.

"We heard evidence that perpetrators who confessed to sexually abusing children went on to reoffend and seek forgiveness again."

"We have concluded that the importance of protecting children from child sexual abuse means that there should be no exemption from the [proposed] failure to report offence for clergy in relation to information disclosed in or in connection with a religious confession," the report authors conclude.

So if a child says they are a victim of ongoing abuse, the priest will do nothing?

It is not quite that simple. The Australian commission heard differing views from a panel of Catholic clerics as to whether a priest would be able to break the seal of the confessional if a child making confession told him that he or she was being abused by an adult.

Two of the panel said that as the sin was not that of the child making confession, it would not fall within the seal of confession.

But Archbishop Anthony Fisher of Sydney told the commission that "if a child penitent confessed their sexual abuse by an adult to him that, 'I believe I'm bound by the seal of confession not to repeat it'."

But priests who take that view would say that, within the confession, they can urge the child to seek help.

Have any other countries enacted similar laws?

The Republic of Ireland's Children First Act of 2015, external requires certain "mandated persons" (which includes Catholic priests) to report child protection concerns to the authorities, and offers no exemption for the confession.

The Catholic Church in Ireland objected to this aspect of the law. It is unclear however whether this part of the act has yet come into force.

In 28 states of the US, clergy are included among those people mandated by law, external to report suspicions of child abuse. Some other states require "any person" to report.

In many of the states, information discovered during a confession would be exempt from the reporting duty, as it would be classed as a "privileged" communication.

In a long-running legal case in the state of Louisiana, a young woman and her family sued a priest and the Catholic diocese, claiming that, at the age of 14, she told her priest during confession that a fellow parishioner had been abusing her - and the priest did nothing to protect her.

Louisiana's Supreme Court eventually ruled that the priest could not be forced to reveal what he had heard in the confessional, external.

What about in the UK?

There is no mandatory reporting law in any part of the UK regarding child abuse suspicions.

A spokesman for the NSPCC told the BBC that it did not believe that wholesale mandatory reporting was the best way to achieve an improvement in reporting and action in response to child abuse:

"Instead we are interested in the proposal for a 'Duty to Act', which would allow professionals to give children the support they need based on their specific situation, without imposing a blanket rule that could ultimately be detrimental."

'Absolute trust'

Catholic commentator and former editor of The Tablet, Catherine Pepinster, told the BBC that she was not in favour of the proposals. "I think if Australia tries to bring this in, they will have a queue of Catholic priests refusing to tell all about the confessional," she said.

"The relationship between the priest and the penitent is one of absolute trust.

"If public authorities are going to insist a priest breaks that confidentiality regarding child sexual abuse, why not for adult rape or for murder as well?"

A priest could use their relationship of trust with the person confessing to encourage them to turn themselves in.

"They could do this by withholding forgiveness - what Catholics call absolution," she explained.

"The greatest sin of all seems to me that some priests had their crimes covered up by their superiors, rather than their confessors. Bishops would move paedophiles around from one parish to another, or one school to another school. That is a real problem rather than confession."

- Published14 August 2017

- Published3 April 2017

- Published20 December 2016

- Published27 September 2015

- Published11 April 2014