Is removing 'Aboriginal' from birth certificates whitewashing history?

- Published

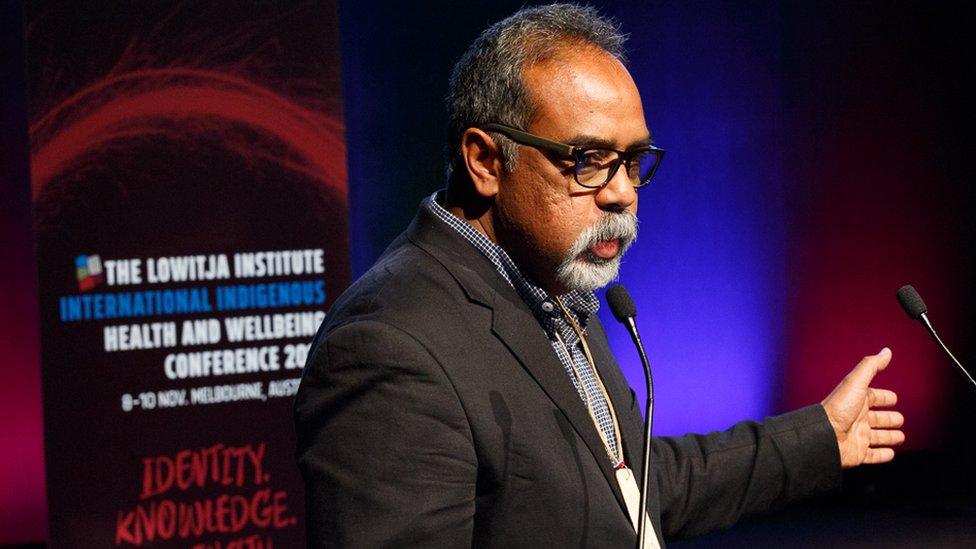

Garry Smith wants Western Australia to stop altering historical birth records

It was never a requirement, but back in the 1800s some clerks in Australia took it upon themselves to add notes about ethnicity to some birth certificates. As the BBC's Frances Mao in Sydney writes, a move to reverse that has generated a new problem.

Garry Smith just wanted to complete a family tree documenting his Aboriginal heritage.

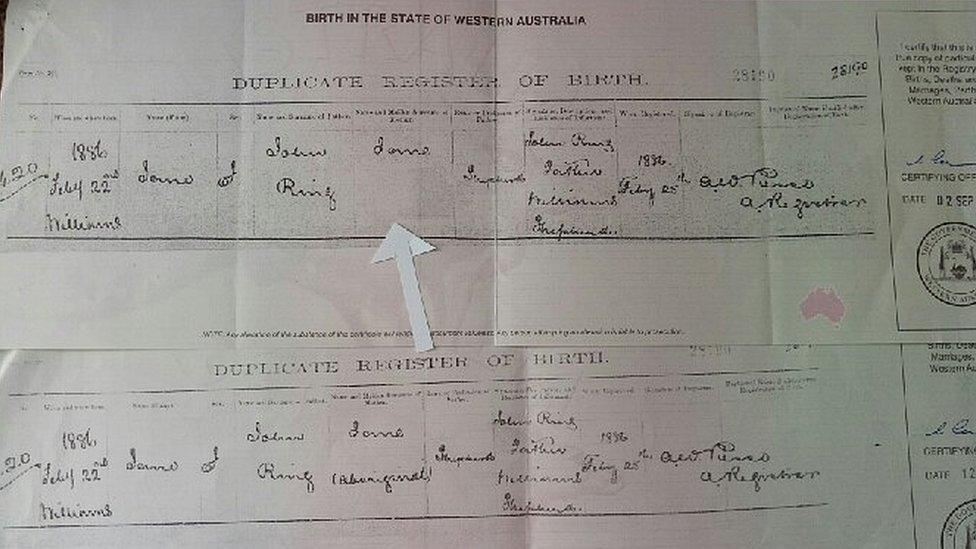

However in 2013, when he retrieved the 19th Century birth certificate for his great-grandmother, he noticed a glaring omission: the word "Aboriginal" had been covered over.

He asked authorities what had happened, and was told the word had been erased due to its "offensive" connotations.

"Having somebody telling you it's offensive, I just stood there and felt a bit sick," he told the BBC.

"Was I supposed to be embarrassed or ashamed to have Aboriginal heritage, ashamed of my father, and great grandparents?"

'Aboriginal is not an offensive word'

Five years later, Mr Smith is still fighting to change the practice.

And it turns out Western Australia's Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages has redacted thousands of racial references in its historical records, because its employees have deemed the terms used offensive.

The practice has sparked controversy, and drawn criticism from Aboriginal Australians and historians who argue the actions amount to a white-washing of history.

A comparison of the two certificates with an arrow pointing to the altered space.

To obtain a copy of his relative's original documentation, Mr Smith said he had to sign a declaration stating that he was not embarrassed by the term Aboriginal.

He retrieved the birth certificate for another relative to check that it "wasn't just a one-off". His aunt's Aboriginal identity had also been removed.

Mr Smith says he and his family have lobbied the state government for years to change the policy. Later this year, they plan on launching legal action, after attempts to mediate through the Australian Human Rights Commission failed.

He told the BBC he was proud to identify as Aboriginal, and did not consider it a derogatory term. Indeed, the Australian government and the United Nations use the word in official contexts to identify the country's indigenous people.

"It just reminds me that they're [the Australian government] still trying to erase Aboriginal history and white that out," says Mr Smith.

'White-washing the past'

Authorities have not clarified when the alteration of records began, although Mr Smith suggested it may have started when the registry began a digital archive of records.

One man's cross-country march for indigenous rights

The department involved has rejected allegations of racism, believing what happened was an attempt to right a historic wrong.

The state had never required a person's race to be noted on a birth certificate, says Registrar Brett Burns. However past authorities had included "unjustified and unsubstantiated personal observations on racial heritage".

That prompted the registry to remove "offensive" terms such as "Chinaman", "native"," nomad" or "half-caste" from its records.

"This does not just apply to Aboriginal people and any suggestion we are 'white-washing' history is wrong", Mr Burns said, calling that accusation "ridiculous and hurtful".

You might also be interested in:

Historians in the state disagree, and argue that historical records should never be altered.

"We rely on documentary evidence for information about the past. Sure [some words] are offensive, but that is the way authorities referred to many people in the past and by redacting them, it's giving a distorted picture of the way things were," Emeritus Professor Jenny Gregory from the University of Western Australia told the BBC.

"It's historical revisionism, it's falsifying history. They are whiting out these words - literally white-washing the past."

Mr Smith says his foremost concern is for other Australians attempting to discover their family history.

"These documents are our personal history, to do with us. It's got nothing to do with anyone else, what's written on them.

"How are you ever going to know who you are, where you come from, when someone's gone in and interfered with these historical documents?"

- Published17 March 2018

- Published3 May 2018

- Published8 February 2018

- Published24 May 2017

- Published28 March 2018