Sam Nzima: The man behind the iconic photo of the fight against apartheid

- Published

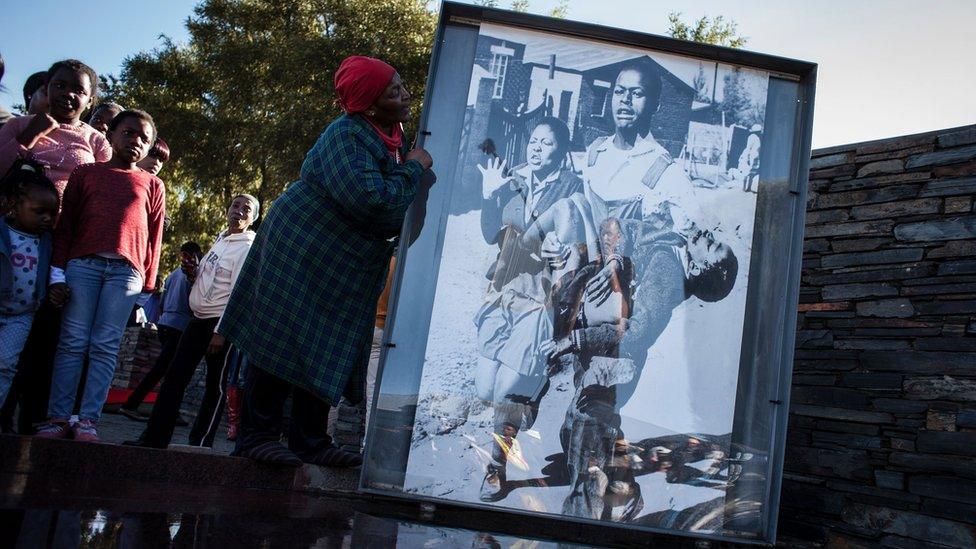

A woman holds the iconic photograph taken by legendary photographer Sam Nzima in 1976

South African photographer Sam Nzima dashed to the scene of a shooting during the June 1976 students' uprising against apartheid just in time to see a child falling to the ground.

It was when another student picked up the dying 13-year-old Hector Pieterson that Nzima clicked to take one of the most iconic photographs in history, becoming a symbol of the brutality of the white minority regime, which flashed around the world.

In a 2010 BBC interview, Nzima, who has died aged 83, recalled: "I didn't know who it was. I saw a child falling down.

"I rushed there with my camera.

"And I saw another young man pick him up and as soon as he had picked him up, I started shooting the pictures.

"It was a very high risk because this picture was taken under a shower of bullets," he said.

The self-taught photographer

Born in August 1934, Nzima, the son of a farm labourer, was fascinated by photography after a teacher at school had shown him how to use his camera.

A young Nzima bought his own camera and began taking pictures in the world renowned Kruger National Park.

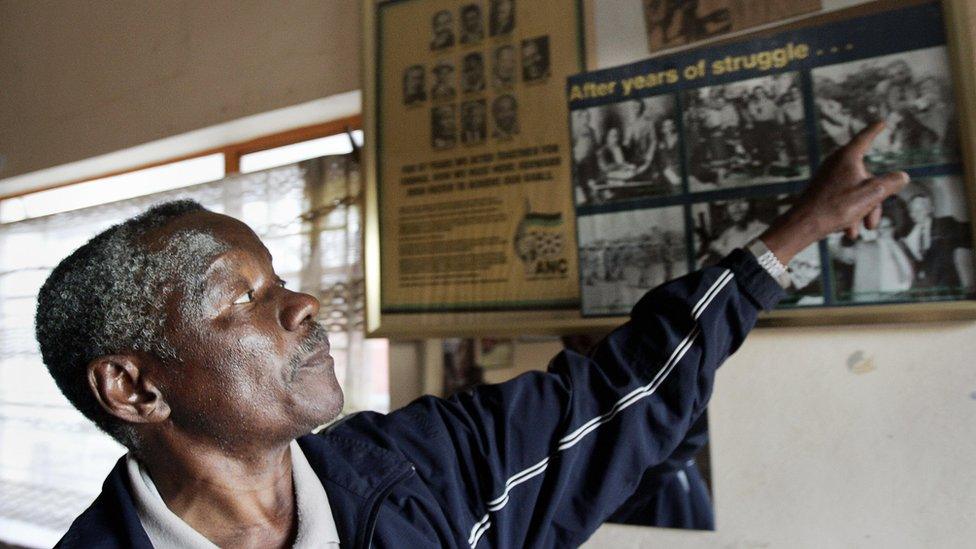

Sam Nzima fled to Johannesburg to escape hard labour

But his own story also illustrated the injustice of the apartheid regime which the students were protesting against.

His father's employer, a white farmer, forced him to work in the Eastern Transvaal, now known as Mpumalanga.

After nine months' hard labour, he ran away to the country's commercial hub Johannesburg, where he found a job as a gardener in one of the posh suburbs.

In 1956 he was employed as a waiter at the Savoy Hotel and began to take portraits of his fellow workers.

He continued honing his skills even after he moved to the Chelsea Hotel and that's where he began reading the Rand Daily Newspaper.

He was transfixed by stories that were critical of the apartheid government written by the late award-winning journalist and editor Allister Sparks in the newspaper.

Nzima started sending his own pictures to The World newspaper and also submitted a story he had compiled while travelling on a bus.

The editor was so impressed with his work that he employed him as a full-time staff photojournalist in 1968.

What was apartheid? A 90-second look back at decades of injustice

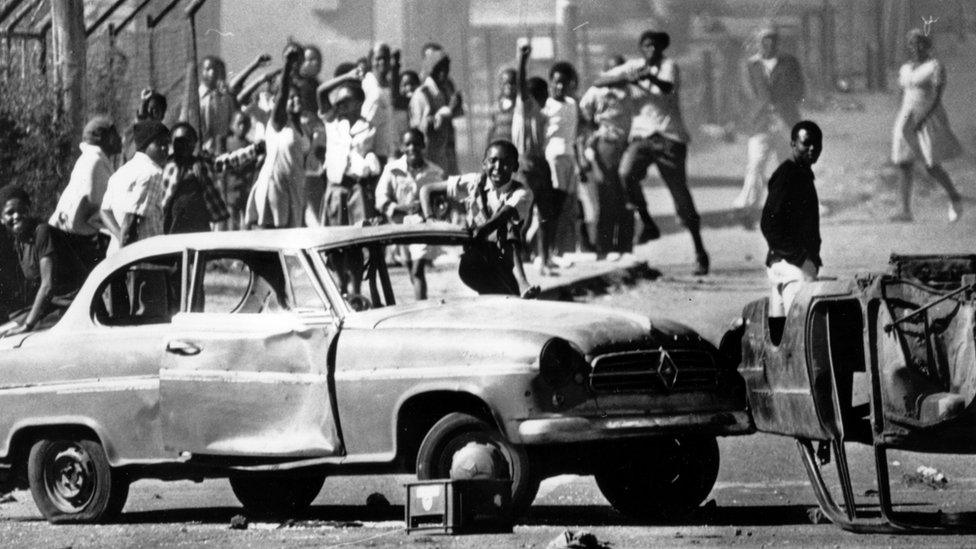

In 1976, high-school students began to protest against being forced to study in Afrikaans - seen as the language of the apartheid regime.

This breathed new life into what had become a lethargic struggle against white minority rule.

The government reacted with brutal force and hundreds of people were killed on that cold Wednesday morning in South Africa's largest township, Soweto.

I was in the crowds and the singing of anti-apartheid liberation songs was powerful.

I saw students with clinched fists raised to the air chanting Black Power.

When the police fired into the crowds, who like me were wearing school uniforms, it was terrifying. It was the very first time I smelled tear gas and saw a trail of white smoke shoot into the air against a blue sky and coming down to choke us.

Students protested against the use of Afrikaans in schools

But it was Nzima's internationally acclaimed photograph that came to symbolise the protests after it was published on the front pages of major newspapers around the world.

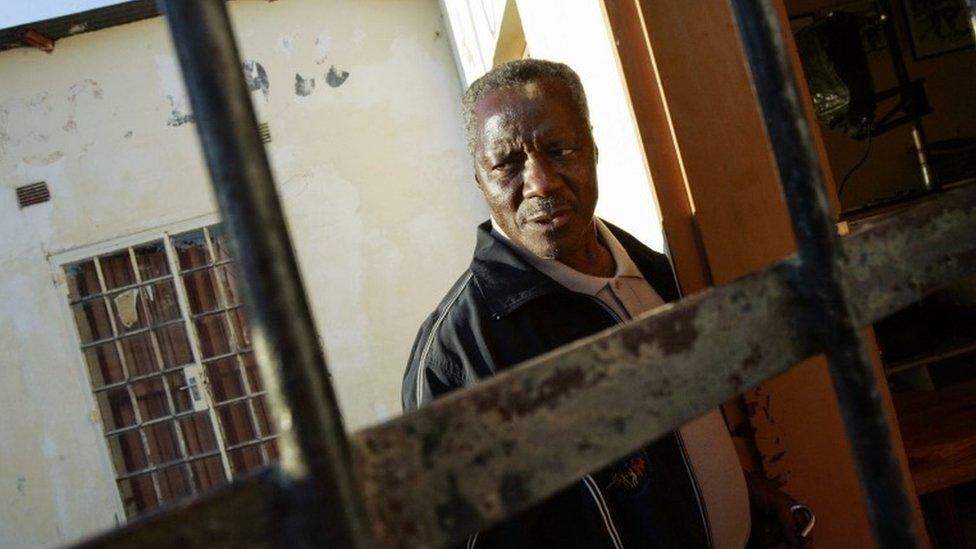

Soon after the uprising, the white minority regime placed Nzima under house arrest for 19 months just for taking that picture.

Time Magazine listed Nzima's iconic photograph as one of the 100 most influential images of all time.

But it was only in 1998 that he finally won a long legal battle to own the copyright of the photograph which he had taken.

It is believed that until then the picture's copyright belonged to the institutions he worked for.

Nzima's son Thulani said this delay cost his father huge amounts of money.

"By the time we got the copyright, those who wanted to use the image for commercial purposes had already extracted the value," he said.

"The second thing is that it took about 18 years for even our own government to finally recognise Sam Nzima as the man behind the picture, while he is still alive.

"In that time, we have seen various applications of the picture, some without even asking for copyrights, and I'm talking even from our government structures."

You may also like:

It is not known how much money he could have earned had his rights to the photograph been recognised from the start but his ultimate success in the courts did not lead to much of a pay-out.

He owned a village liquor store, and was not a wealthy man when he passed away.

He also served as a local councillor in Mpumalanga.

'The camera was an extension of his body'

Nzima was honoured with the bronze National Order of Ikhamanga on Freedom Day in 2011, when the president bestows South Africa's highest honours to individuals who have contributed to the betterment of the republic.

"This means a lot to me and my family," he said at the time.

"I had so many awards in my life but this will be very close to my heart because it will be coming from the president of the country."

President Cyril Ramaphosa, one of the anti-apartheid struggle's student activists, also sent his condolences.

In a statement he said: "Sam Nzima was one of a kind.

"We will especially remember his iconic photograph of a dying young Hector Pieterson, which became a symbol of resistance against the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in the black schools."

Sam Nzima struggled to survive after he was forced to leave his job

An old friend of Nzima's, Prof Somadoda Fikeni said: "Sam Nzima was humility personified. He was always down to earth and he inspired me to finish my own photography course."

"I do think that a click of one image, which became iconic, was the best way to speak a million words to the world as to what was happening behind the iron curtain of apartheid," Mr Fikeni told local media.

Veteran journalist Thami Mzwai who worked with Nzima in the 1970s, including covering Steve Biko's funeral together, said: "He was a rare breed of a photo-journalist.

"The camera was an extension of his body.

"It automatically clicked.

"The image became a living testimony of what the journalist was writing about because the apartheid police were very quick to deny their acts of brutality."

He also did his best to inspire the next generation of photographers by setting up a photography school in Mpumalanga.