Covid: The lives upended by Australia's sealed border

- Published

Kristina Sahleström was forced to watch her mother's funeral over a phone

It has been 18 months since Australia snapped shut its international borders.

Locking itself away was the country's primary defence against the spread of Covid-19.

"I'm not going to take risks with Australians' lives" was the mantra of Prime Minister Scott Morrison for well over a year.

And it largely worked. Despite the current Sydney and Melbourne outbreaks, just over 1,100 people have died from the virus since the pandemic began. Only around 30 nations globally have lower deaths per capita.

But as the world opens up, there is no certainty when Australia will do the same. Even though it has given up on pursuing zero Covid, most Australians find themselves either locked out or locked in. And right now around 10 million are also locked down.

A national plan gives hope of some international travel once 80% of the eligible are fully vaccinated. Home quarantine is also being trialled as an alternative to hotel quarantine.

But double vaccination rates are currently just 40%. A rollout for teenagers is only now beginning. And Western Australia, which has kept Covid-19 cases to near-zero, has hinted it may keep travel restrictions in place far longer.

We've been hearing hundreds of tales of separation, despair and tragedy. Here are just a few.

The missed funeral

Kristina Sahleström's mother Ylva with her grandchild, on her last visit to Sydney

Australian citizens and permanent residents need an exemption to leave the country. If they intend to return, usually they must agree they'll be away at least three months.

Tens of thousands of exemptions have been granted, including many on compassionate grounds. But tens of thousands more have been refused.

Kristina Sahleström lives in Sydney. Her mum Ylva died suddenly in Sweden in late July.

Kristina says she was twice refused permission to travel back, and so missed the funeral. She had to watch the cremation online.

"My family told me it was very peaceful, but when you see it on a small phone, that translation of peace doesn't come," she says.

"I wanted to be there for selfish reasons, for the sake of me and processing my grief and dealing with the shock of something happening so quickly. And I feel a lot of guilt that I left my brother alone.

"But also it was the respect of being there as her daughter. It's a level of respect I think she should have been given.

"They were unnecessarily harsh, when compassion should have been shown. It's a blanket rule that doesn't allow for the differences in situations."

The separated partners

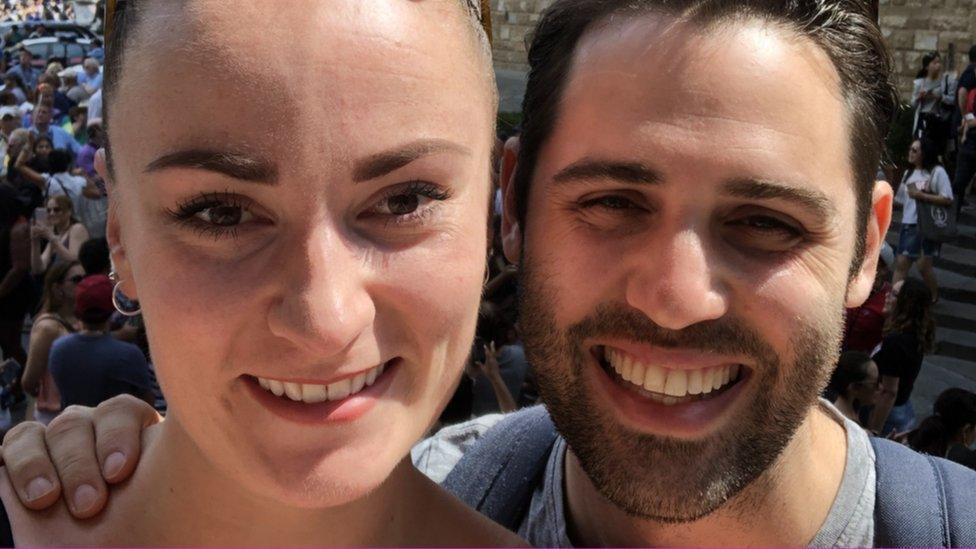

Kathryn Relf and Mikey Votano have spent more than 18 months apart

Mikey Votano is a musician and entertainer from Sydney. His partner Kathryn Relf is in the UK.

"We both work on cruise ships and have been together five years. Our pre-Covid life was spent between Australia and Britain, but Kathryn and I were separated at the start of the pandemic and haven't been able to see each other since," he says.

"We've requested for her to join me here in Australia, but all the requests have been denied. We've paid a ridiculous amount for lawyers to try and get a visa for Kathryn to come to Australia, but are still waiting to hear."

"I've had offers to do work in Europe but until recently hadn't been able to get vaccinated. I just had my first dose of Pfizer last week.

"There's work booked in Europe for June 2022, which will be my first contract in two-and-a-half years. But with the border closures and flight costs I have no guarantee I'll be able to leave.

"The lockdowns in Australia have devastated the entertainment industry. Many artists, including myself, were denied welfare support."

The stranded Australian

Rachael Marciniak, 44, lives in the UK.

Like an estimated 30,000 Australians overseas, she wants to get home. But tight caps on quarantine hotels mean only a few hundred a week get that wish.

A quarantine place costs A$3000 (£1,600; $2,200). Flights into Australia can cost many times that amount, and are regularly cancelled.

Anyone whose return is only temporary must get an exemption to leave Australia again.

"My mum in Melbourne has been diagnosed with lung cancer. She is getting palliative care and I need to get back to see her as soon as I can," she says.

"It's been an insane rollercoaster trying to get home. I've just missed out on the September repatriation flights that the Australian government runs with Qantas. I'm on a waiting list for last-minute cancellations.

"I've lived in London since 2006, have built a life here and have a young family. The last time I saw mum was December 2017 when I introduced my first daughter to her. She hasn't met my second child in person but longs to. Heart-breaking is an understatement.

"Even if I make it to Australia, I'll then have to plead for an exemption to be allowed to return to my life and family in the UK. How can I leave my kids here when there's no certainty I can get back to them?

"How can high-profile people enter Australia so easily whilst we sit here grasping at any hope as an Australian citizen?

The struggling new parents

Mahtab Moalemi desperately wants help from her mother, Sima

Besides bereavement, one of the most common struggles we've heard about comes from new parents.

Mahtab Moalemi gave birth to twins prematurely through a planned C-section.

She has faced a "huge struggle" since and longs for her mother, who lives in the Iranian capital Tehran.

"I desperately want my own mother to be here to support me and help me. She is fully vaccinated and I have applied three times for her to be allowed into Australia on compassionate grounds, but each one has been refused.

"The impact has been huge. I wasn't able to properly take care of my newborn twins. And my breastfeeding journey came to an early end, after I had an anxiety attack following one of the exemption denials.

"I'm back to work part time and I'm still struggling with work, life, housework and taking care of two babies. I've fallen into the deepest depression.

"My husband and I have a few friends in Perth, but not really much support. I can't go back to Iran, as my husband is Australian. We are seriously thinking of moving to another country."

The expat selling up

Marissa Parkin wants daughter Zadie to better know her grandparents

Some have decided enough is enough.

Marissa Parkin, a US citizen, and her husband, Ian, a Brit, just sold their Sydney home and are leaving Australia. They'll spend time in the US before starting a new life in Nottingham, England, with daughter Zadie.

"We're so, so sad. We've made a life here, we both have fantastic jobs, we have a beautiful home and our daughter was born here. We really never thought we'd leave... but we haven't seen our families for 18 months now.

"At first I really got it. I understood that halting the movement of people was what needed to happen. But it's dragging on, with no path out.

"Ultimately It just comes down to family. Our daughter needs to know her grandparents. She thinks they live in a computer.

"It's not wasted on us at all how incredibly lucky we are to have options and to be mobile. We're grateful we have the choice and we're going to take it, but it's not without a heavy heart."

More on Covid in Australia:

"Heartless" Queensland bars US couple from seeing dying father