Australia election 2022: What will the vote mean for climate policies?

- Published

Scott Morrison's government has drawn protests and criticism for its perceived inaction on climate change

When Australia - long considered a climate policy laggard - heads to the polls on 21 May, the outcome could be significant for the planet's future.

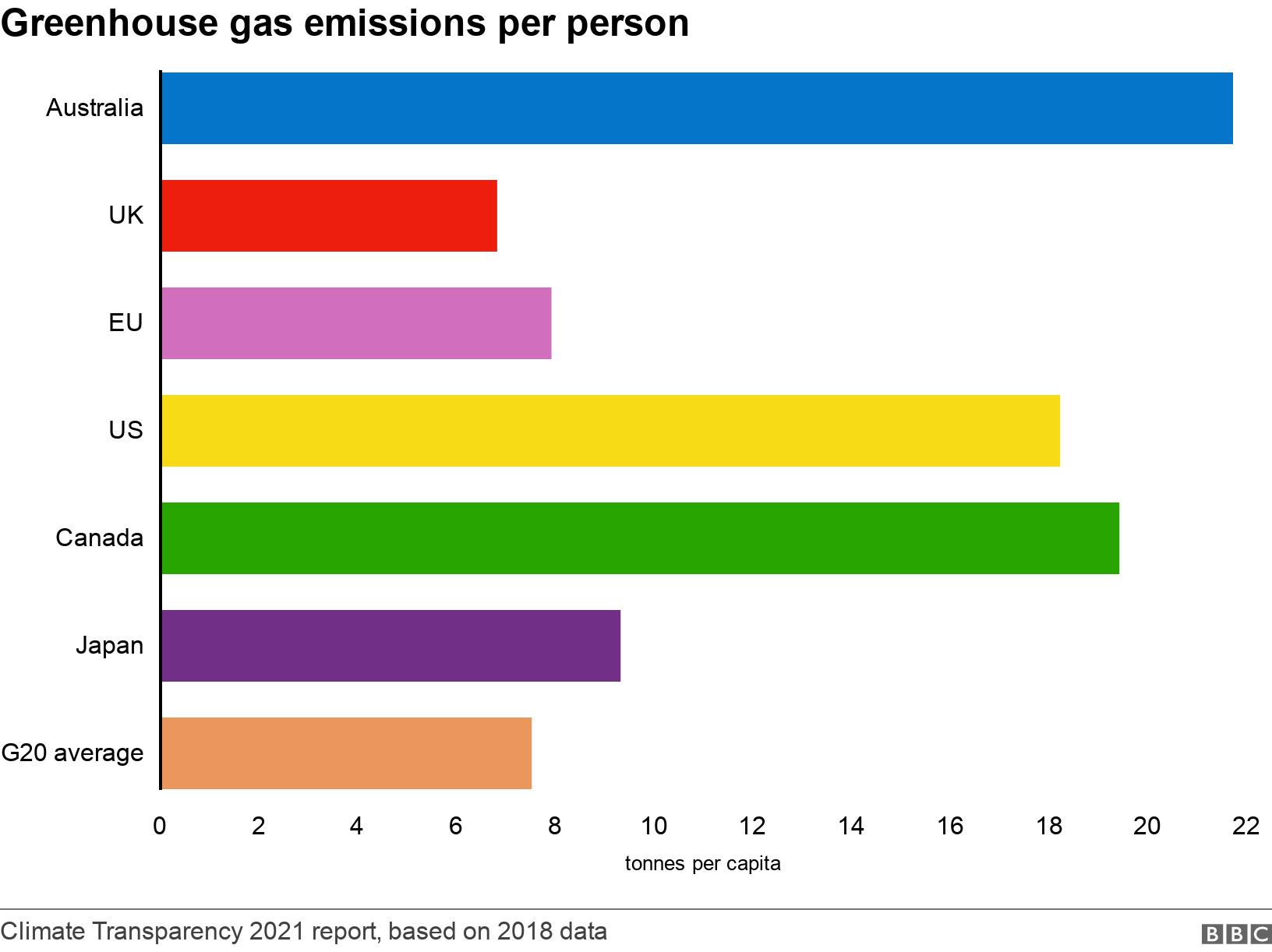

Still reliant on coal for most of its electricity, it is one of the dirtiest countries per capita - making up just over 1% of global emissions, but only 0.3% of the world's population.

It's a massive global supplier of fossil fuels, and once that is factored in, it accounts for 3.6% of the world's emissions, external.

But it's also one of the nations most at risk from climate change.

In recent years, Australia has suffered severe drought, historic bushfires, successive years of record-breaking floods, and six mass bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef.

And it's racing towards a future full of similar disasters, the latest UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report warns.

The current government has angered allies with its short-term emissions reductions target - which is half what the IPCC says is needed if the world has any chance of limiting warming to 1.5C.

But Australia is still wedded to fossil fuels and climate policy has famously played a role in toppling three prime ministers in a decade.

Though most voters want tougher climate action, external, some coal towns lie in swing constituencies that are key to winning elections.

What is the government promising?

Scott Morrison famously praised coal's value to Australia in a parliamentary debate on renewable energy in 2017

After years of warring within the Liberal-National coalition, Scott Morrison's government committed to a 2050 net zero emissions target at the last gasp before last year's Glasgow COP26 summit.

Deputy PM and National Party leader Barnaby Joyce remains personally opposed to the policy, claiming people in regional areas would have to "grab a rifle [and] go out and start shooting [their] cattle" to meet the goals.

Australia's 2030 emissions reduction target of 26% on 2005 levels - half the US and UK benchmarks - has been called "a great disappointment".

Mr Morrison has boasted the country is on track to achieve 35%. Yet that's unlikely, vice chair of the IPCC and Australian National University Professor Mark Howden says, unless the government - which has been in power since 2013 - overhauls its "technology over taxes" approach.

Once emissions saved by a drastic reduction in land clearing are excluded, Australia's carbon footprint has actually increased "significantly" since 2005, he notes.

And Mr Morrison's plan to bring it down has been criticised for hanging on technologies that do not exist yet.

"That's what we call a moral hazard - we make the assumption that the solution will pop up so we don't take action now," Prof Howden told the BBC.

Critically, coal mines and power stations are safe on Mr Morrison's watch.

Labor will cut more, faster

The opposition Labor party's 2030 emissions reduction target of 43% is "far more ambitious", Prof Howden says.

"If you're looking at the difference between those goals, it's like taking every car off the road."

If global leaders set targets similar to the coalition's, the world would be heading towards "potentially terrifying" warming of more than 3C, he says.

Labor's target is more consistent with warming of about 1.6C or 1.7C.

While it is still short of the IPCC recommendation, Labor leader Anthony Albanese has defended it as in line with key trading partners like Canada (40-45%), South Korea (40%) and Japan (46%).

Leader Anthony Albanese has defended the Australian Labor Party's policy as similar to countries like Canada, South Korea and Japan

Labor has stressed its policy will not leave "emissions intensive" industries - like mining - at a disadvantage to their global competitors.

It has also promised it will support new coal mines if they make commercial sense, and that it will not force coal-fired power stations to shut early.

Instead the party says it will make electric cars cheaper, improve renewable energy storage options, and gradually lower the threshold at which big emitters need to buy carbon offsets.

Like the coalition, Labor is hoping the market will phase out coal without intervention, which Prof Howden says is risky.

"The maths tells us we can't afford to put in new large fossil fuel infrastructure, and the infrastructure that we have currently we have to take out of the system fairly quickly."

Could minor players have the final say?

Australian elections are generally a contest between Labor and the Liberal-National coalition.

The party with the majority of the 151 seats in the lower house of parliament governs, and only twice in the country's history has no party achieved a majority - in 1940 and 2010.

But voters are increasingly shunning the major parties and in the event of another hung parliament, the government would need support from the crossbench to pass legislation.

Liberal-National coalition:26-28%

Labor:43%

Teal independents:50-60%

Greens:75%

A bevy of high-profile candidates - dubbed the "teal independents" - hope that will mean they can negotiate a 2030 target of at least 50% if they are elected and hold the balance of power.

But the future government could also turn to minor party MPs.

The Greens say net zero by 2050 is a death sentence, and the party would push for a 75% cut by 2030, and net zero five years after that.

On the other hand, the far-right One Nation Party proudly calls itself the only party to question climate science and wants the country's targets scrapped.

Australia's climate debate has been "toxic", Prof Howden says, but he's optimistic it is turning a corner.

"We actually do have the technology and the capability to reduce our emissions much faster than we have done.

"If we get potentially a hung parliament... I think we could actually end up with very significant climate action and people will start to see the benefits of that fairly quickly."

You may also be interested in:

Watch: Anger and trauma in Australia’s flood aftermath

Related topics

- Published22 October 2021

- Published11 April 2022

- Published25 March 2022

- Published15 March 2022