Australia election: Why is Australia's parliament so white?

- Published

Some of Australia's MPs, pictured here, fail to reflect the country's diversity, critics say

Australia is one of the most multicultural nations in the world, but it's a different story in the country's politics, where 96% of federal lawmakers are white.

With this year's election, political parties did have a window to slightly improve this. But they chose not to in most cases, critics say.

Tu Le grew up the child of Vietnamese refugees in Fowler, a south-west Sydney electorate far from the city's beaches, and one of the poorest urban areas in the country.

The 30-year-old works as a community lawyer for refugees and migrants newly arrived to the area.

Last year, she was pre-selected by the Labor Party to run in the nation's most multicultural seat. But then party bosses side-lined her for a white woman.

It would take Kristina Kenneally four hours on public transport - ferry, train, bus, and another bus - to get to Fowler from her home in Sydney's Northern Beaches, where she lived on an island.

Furious locals questioned what ties she had to the area, but as one of Labor's most prominent politicians, she was granted the traditionally Labor-voting seat.

Ms Le only learned she'd been replaced on the night newspapers went to print with the story.

"I was conveniently left off the invitation to the party meeting the next day," she told the BBC.

Ms Le with Labor Party leader Anthony Albanese

Despite backlash - including a Facebook group where locals campaigned to stop Ms Kenneally's appointment - Labor pushed through the deal.

"If this scenario had played out in Britain or the United States, it would not be acceptable," says Dr Tim Soutphomassane, director of the Sydney Policy Lab and Australia's former Race Discrimination Commissioner.

"But in Australia, there is a sense that you can still maintain the status quo with very limited social and political consequences."

An insiders' game

At least one in five Australians have a non-European background and speak a language at home other than English, according to the last census in 2016.

Some 49% of the population was born or has a parent who was born overseas. In the past 20 years, migrants from Australia's Asian neighbours have eclipsed those from the UK.

But the parliament looks almost as white as it did in the days of the "White Australia" policy - when from 1901 to the 1970s, the nation banned non-white immigrants.

"We simply do not see our multicultural character represented in anything remotely close to proportionate form in our political institutions," says Dr Soutphomassane.

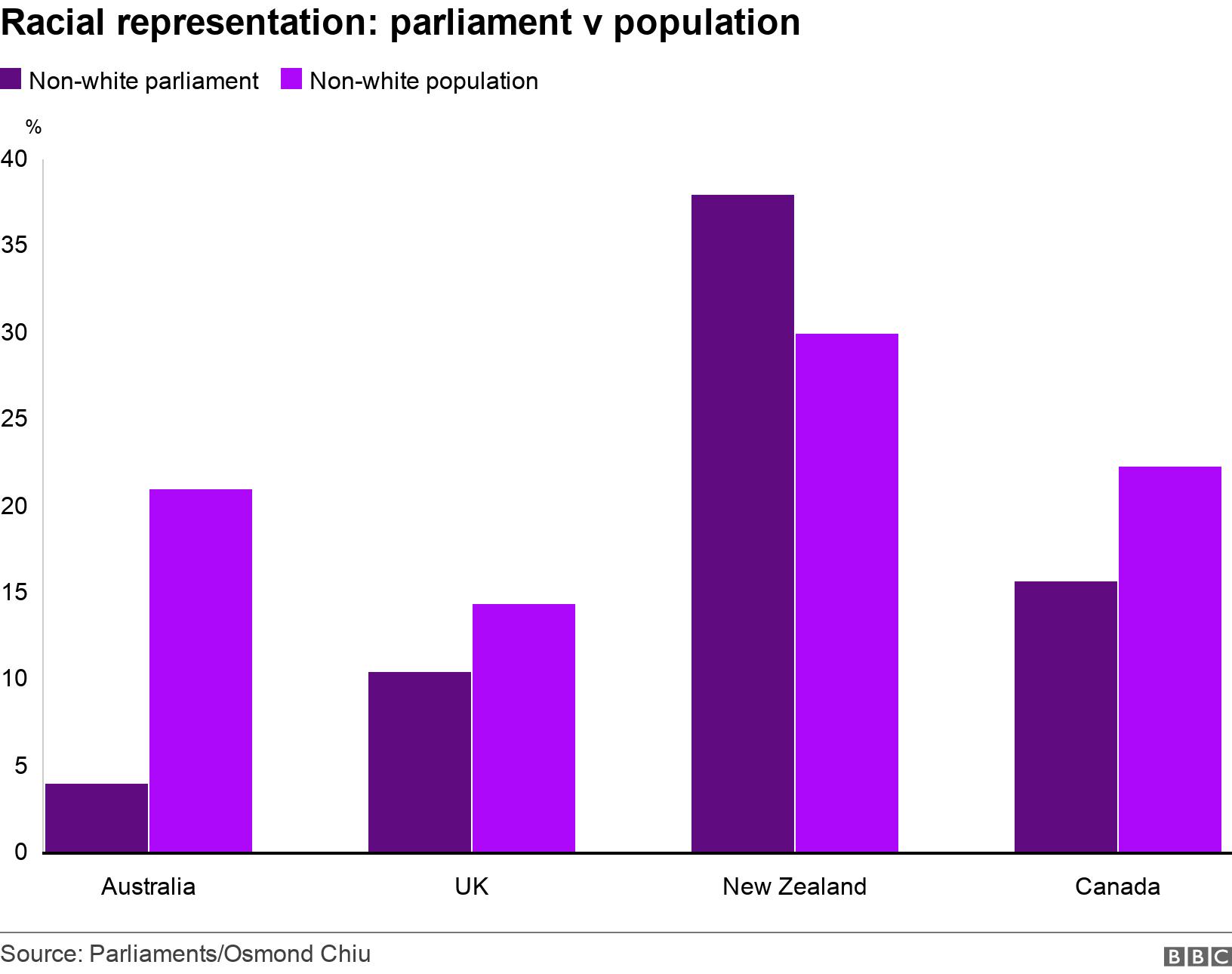

Compared to other Western multicultural democracies, Australia also lags far behind.

The numbers below include Indigenous Australians, who did not gain suffrage until the 1960s, and only saw their first lower house MP elected in 2010. Non-white candidates often acknowledge that any progress was first made by Aboriginal Australians.

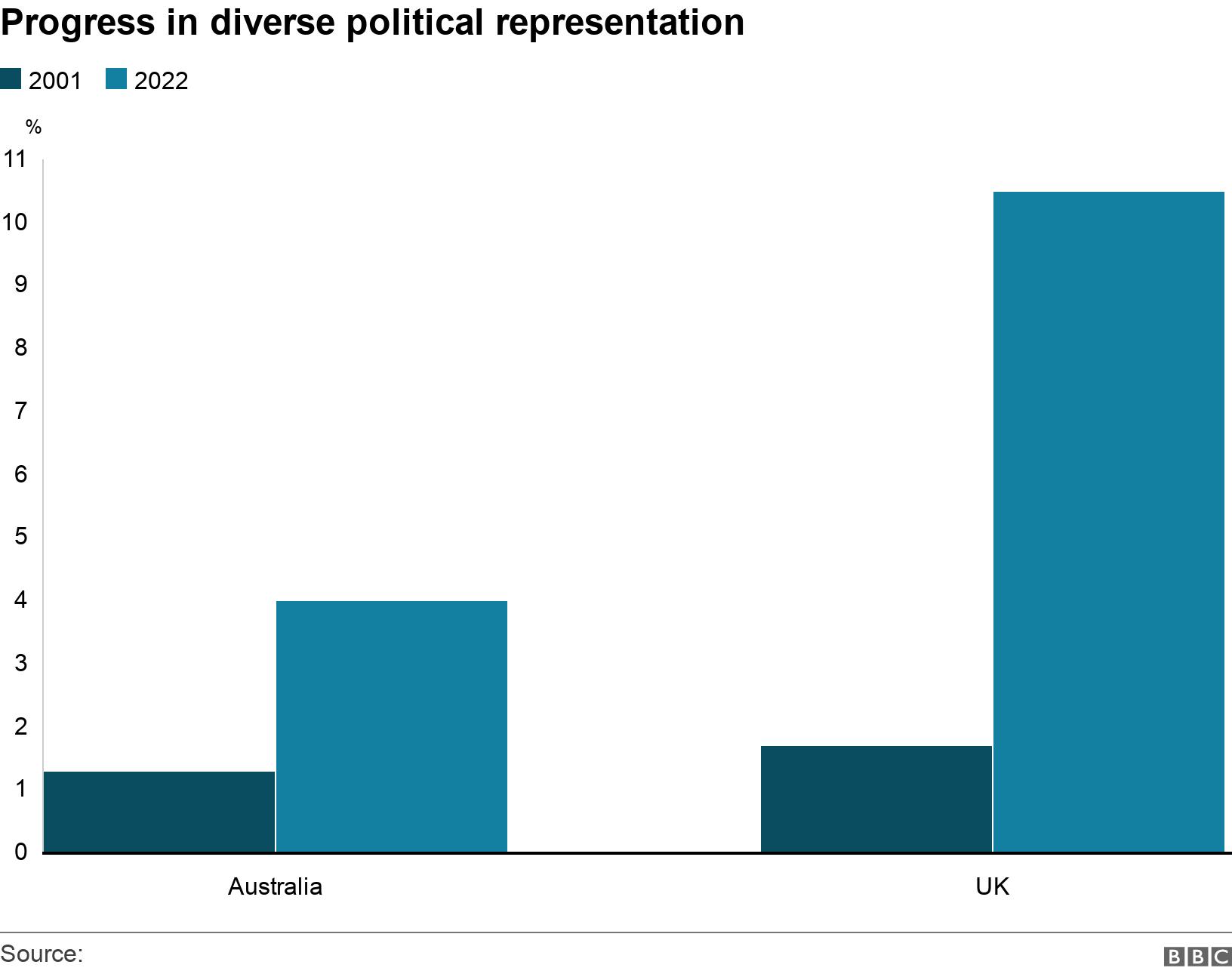

Two decades ago, Australia and the UK had comparably low representation. But UK political parties - responding to campaigns from diverse members - pledged to act on the problem.

"The British Conservative Party is currently light years ahead of either of the major Australian political parties when it comes to race and representation," says Dr Soutphomassane.

So why hasn't Australia changed?

Observers say Australia's political system is more closed-door than other democracies. Nearly all candidates chosen by the major parties tend to be members who've risen through the ranks. Often they've worked as staffers to existing MPs.

Ms Le said she'd have no way into the political class if she hadn't been sponsored by Fowler's retiring MP - a white, older male.

Labor has taken small structural steps recently - passing commitments in a state caucus last year, and selecting two Chinese-Australian candidates for winnable seats in Sydney.

But it was "one step forward and two steps back", says party member and activist Osmond Chiu, when just weeks after the backlash to Ms Le's case, Labor "parachuted in" another white candidate to a multicultural heartland.

Andrew Charlton, a former adviser to ex-PM Kevin Rudd, lived in a harbour mansion in Sydney's east where he ran a consultancy.

His selection scuppered the anticipated races of at least three diverse candidates from the area which has large Indian and Chinese diasporas.

More on Australia's election:

What do Indigenous Australians want this election?

Party seniors argued that Ms Kenneally and Mr Charlton - as popular and respected party figures - would be able to promote their electorates' concerns better than newcomers.

Labor leader Anthony Albanese also hailed Ms Kenneally as a "great Australian success story" as a migrant from the US herself.

But Mr Chiu says: "A lot of the frustration that people expressed wasn't about these specific individuals.

"It was about the fact that these were two of the most multicultural seats in Australia and these opportunities - which come by so rarely - to select culturally diverse candidates were squandered."

He adds this has long-term effects because the average MP stays in office for about 10 years.

The frustration on this issue has centred on Labor - because the centre-left party calls itself the "party of multiculturalism".

But the Liberal-National government doesn't even have diversity as a platform issue.

One of its MPs up for re-election recently appeared to confuse her Labor rival for Tu Le, sparking accusations that she'd mixed up the two Asian-Australian women - something she later denied. But as one opponent said: "How is this still happening in 2022?"

Some experts like Dr Soutphommasane have concluded that Australia's complacency on areas like representation stems from how the nation embraced multiculturalism as official policy after its White Australia days.

The government of the 1970s, somewhat embarrassed by the past policy, passed racial discrimination laws and "a seat at the table" was granted to migrants and Indigenous Australians.

But critics say this has led to an Australia where multiculturalism is celebrated but racial inequality is not interrogated.

"Multiculturalism is almost apolitical in how it's viewed in Australia," Dr Soutphommasane says, in contrast to the "fight" for rights that other Western countries have seen from minority groups.

What is the impact?

A lack of representation in parliament can also lead to failures in policy.

During Sydney's Covid outbreak in August 2021, Fowler and Parramatta electorates - where most of the city's multicultural communities reside - were subject to harsher lockdowns as a result of a higher number of cases.

The electorate of Fowler is one that is home to a large multicultural population

Ms Le and others argue it was because the policies designed to contain the spread were crafted by those who didn't understand those communities' realities.

Policies like working from home could not apply for the many residents in insecure work; reliant on paid-per-hour jobs like cleaning or food delivery where there's little if any sick leave.

Isolation requirements also didn't account for the reality of multi-generational families living in the same household, often sharing rooms.

How will things change?

Liberal MP Dave Sharma, the only lawmaker of Indian heritage, has said all parties - including his own - should better recruit people with different backgrounds. He called it a "pretty laissez-faire attitude" currently.

Mr Albanese has urged Ms Le to "hang in there", insisting she has a future.

But more people like Ms Le are choosing to speak out.

"I think I surprised a lot of people by not staying quiet," she told the BBC.

"People acted like it was the end of my political career that I didn't toe the party line. But... none of that means anything to me if it means I'm sacrificing my own values."

About half of Australians were born overseas or have a parent who was

She and other second-generation Australians - raised in a country which prides itself on "a fair go" - are agitating for the rights and access their migrant parents may not have felt entitled to.

"Many of those from diverse backgrounds were saying they felt like they didn't have a voice - and that my case was a clear demonstration of their suppression, and their wider participation in our political system."

She and others have noted the "growing distrust" in the major parties. Polls are predicting record voter support for independent candidates.

"This issue.... matters for everyone in Australian society that cares about democracy," says Mr Soutphommasane.

"If democratic institutions are not representative, their legitimacy will suffer."

2 September: A chart in this article has been updated to reflect New Zealand's parliament representation figures, which were inaccurately established in the first version of the story.

Related topics

- Published27 June 2017

- Published17 May 2022

- Published7 May 2022