Georgia and Russia still bitter foes amid scars of war

- Published

The town of Gori was badly damaged during heavy fighting that spread from nearby South Ossetia

Georgia and Russia are marking the second tense anniversary of their brief but destructive conflict in the breakaway region of South Ossetia.

As the two countries continue to trade verbal blows Georgia's people live in fear of further violence amid a fragile peace.

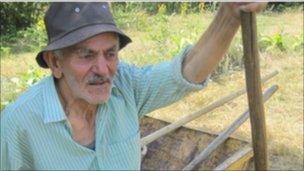

In a dry, grassy field Nikoloz Barishvili is bent over a pitchfork.

As he lifts light strands of golden grass into irregular piles, without pausing to mop his brow, he tells me how August always brings back bad memories. "Of course I get worried. South Ossetia is just over there," he says, pointing towards his apple orchard.

The war two years ago consolidated the virtual boundary between South Ossetia - a breakaway territory whose independence Russia backs - and Georgia. The line now runs 500m from the village, Ditsi, where Mr Barishvili lives.

"We used to come across the South Ossetian militia all the time. Since the war, some of our farmland has been cut off," says the 78-year-old, who grew up there.

"We have relatives and friends there - but if we go there the South Ossetians or the Russians will capture us," he says.

His tale is a throwback to the 2008 conflict and the stiff lines it drew between Georgia and the pro-Russian territory of South Ossetia. But what has changed since then?

Georgian police officers in armoured vehicles still keep close watch nearby - an immediate reminder of the insecurity along the border. But it is calmer than in previous years, when rocket fire and gun battles were commonplace.

The presence of more than 200 European Union monitors on one side of the boundary line may be helping the situation. But the Russians say their border guards and the stationing of several hundred troops - on the other side - are also a contributing factor.

"Due to the co-ordinated activity of Russian servicemen and border guards, together with law enforcement agencies (in) Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the situation on the borders has considerably stabilised," Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Grigoriy Karasin said, quoted by the Itar-Tass agency this week.

However, the opposing rhetoric from both sides highlights the gulf between them. If you are a member of the Georgian government, Russia is an aggressor and occupier.

"It was Russian forces which crossed the state border (in August 2008). There are Georgian territories which are occupied," says Nikoloz Vashakidze, Georgia's Deputy Defence Minister.

"These realities offer a clear picture about who was the aggressor in this war. No PR strategies or tricks can change this reality," he tells me.

Hoax invasion

It is hard to see how Georgia and Russia can achieve reconciliation when they have such differing views of the situation on the ground.

To Russia, South Ossetia and Abkhazia are now "independent" states, though heavily reliant on Russia economically and - in the case of South Ossetia - politically too.

To Georgia, they will always fall under Georgia's sovereignty. And anyone who takes an alternative view is likely to be accused of treachery.

Two opposition politicians have travelled to Moscow to seek Kremlin support in the last year - only to be booed on their return to Tbilisi.

In March, the pro-government TV station Imedi ran a hoax report in which Russia was shown invading Georgia. It provoked panic; people blamed Mikheil Saakashvili's government for orchestrating it.

But its desired effect may have been to discredit figures like Zurab Nogaideli, an opposition politician who earlier this year met Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin in Moscow.

"The Imedi hoax did not work. And I am going to continue to fight. What we need is to start talking with Russians to address our problems - and this is what a majority of Georgians are demanding and to start negotiating without any ultimatum," says Mr Nogaideli, a former prime minister.

However, the majority of Georgians appear to be less preoccupied with the war and the fractious relationship with their northern neighbour than they were last year or the year before.

Holiday optimism

On the country's Black Sea coast, during the August holiday season, tourist numbers are rising.

The resort of Batumi acts like a magnet, attracting Georgians from dry inland areas, but it is popular with Russian speakers too.

Sun-drenched tourists from Ukraine can be overheard, as can those from Armenia, Belarus and some from Russia itself.

Some houses on both sides of the South Ossetian boundary line have not been repaired

"Everyone remembers the war. Summer is like a scar on people's memories. People want a better life. They do not want to look back, hoping there won't be another war," says Levan, a Georgian who runs a seaside amusement stand.

Judging by the warm smiles on people's faces, war could not be further from their minds.

"I am not just talking about Georgians - everyone who comes here feels optimistic," says Levan.

As the voices of the holidaymakers are drowned out by the Russian pop music, I am reminded of something that has been true for a long time - that, away from the frontlines and the uncertainty, Russians and Georgians largely like each other, even if their governments are on bitter terms.

"Some people want better relations with Russia. But politically it is not important," says Ghia Nodia, director of the School of Caucasus Studies at Ilia State University in Tbilisi.

"Vladimir Putin cannot openly deal with Saakashvili without losing face. President Saakashvili would not see much in it for him."

Back in the grassy fields of central Georgia, Nikoloz Barishvili is loading up his donkey cart with hay.

"We used to get on perfectly well with the Ossetians before the war. Their militia would at times be violent, but we used to trade at the same market. That cannot happen now."

The people of Ditsi don't have hard feelings for those living on the other side of the boundary and - far removed from the politics as they are - they simply dream of a time when it is safe enough for the virtual boundary to disappear.

The World Tonight is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 weekdays at 2200 BST, or listen again on BBC iPlayer.

- Published6 July 2010

- Published5 July 2010

- Published14 July 2010