Banksy supports Voina, controversial Russian art group

- Published

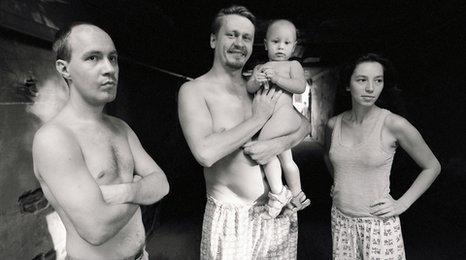

Voina members Leonid Nikolayev (l) and Oleg Vorotnikov (c) were arrested in November

Graffiti artist Banksy is to donate £90,000 from a print sale to a controversial Russian art group called the Voina (War) collective, two of whose members are in prison awaiting trial.

Banksy heard about Voina's work through a report on the BBC's From Our Own Correspondent by Lucy Ash, who met the group's founders in October.

I was about to interview a mayor in a remote hilltop village in Calabria when my mobile rang. It felt a bit surreal and I wondered at first if the call was a hoax. After all, it is not everyday you get phoned up by one of the world's most elusive artists.

Of course it wasn't Banksy himself - it was his publicist, Jo. She told me that the master of satirical street art had heard my report about a group of Russian artists who had been thrown into jail and that he wanted to help.

"How much do you reckon it'll cost," she asked, "to get them out?"

Uncharacteristically, I was lost for words. I mumbled that I was not sure whether he could help get them out of prison, but that I was certain that the artists would be most grateful for his support.

Voina held a funeral feast on the Russian metro for dissident poet Dmitry Prigov in 2007

I met the Slav art provocateurs a couple of months ago in Moscow. Although the name of the group is Voina or "War", its methods are non-violent, and its weapons are satire and showmanship rather than knives and shotguns.

Last June, the politically-conscious art collective caused a stir when it painted a huge phallus on a drawbridge in St Petersburg.

As the Liteiny Bridge opened to let ships pass down the Neva, the erect phallus - 65m tall and 27m across - sent an unmistakable message to a building directly opposite - the local headquarters of the KGB's successors, the Federal Security Service.

In another stunt designed to expose police impunity, one member of the group went into a supermarket wearing a police uniform.

He filled five bags with the most expensive food he could find and calmly walked out without paying. Nobody challenged him.

'You can call me Thief'

Still more daringly, in September, Voina members overturned several police patrol cars.

That involved 31 activists; five to do the heavy lifting, while the rest filmed what was happening, acted as lookouts and distracted the police by pretending to be lost tourists.

Having seen Voina's videos on the internet, I was keen to meet the people behind the group, but it proved tricky.

I had been emailing someone called Sandra. She would not give me a phone number but arranged a late night rendezvous outside a Moscow metro station.

As I stood waiting I realised I had no idea what she looked like. To make matters worse, a guy in a hooded blue jacket kept eye balling me. I turned my back and walked a few paces away.

Leonid Nikolayev wore a blue bucket to protest against police misuse of emergency lights

"Lucy?" he said. "Lucy from BBC?" I swung around, defensively. "Pleased to meet you," he said. "I'm the Sandra you're waiting for but you can call me Thief."

It dawned on me that this bloke with a scraggy blonde beard must be Oleg Vorotnikov. I recognised the activist who dressed as the shoplifting policeman, and one of the founders of Voina.

He set it up three years ago with a group of fellow students from the philosophy department of Moscow State University.

Standing next to him was a small, pale faced woman in a woolly hat who was introduced as Kozlyonok or Little Goat.

Her real name is Natalia Sokol, and she is a physics graduate with a day job involving cancer research. A 16-month-old toddler called Casper clung to her coat.

I also met Voina's president, Leonid Nikolayev, known as Crazy Lenya.

'Morale boost'

He is famous for climbing onto a state security officer's car with a blue bucket on his head to protest against the widespread use of blue emergency lights by officials who cannot be bothered to sit in Moscow traffic jams.

Why wasn't he scared of getting run over or arrested, I wondered? "Our society has lived in fear for so many decades, we are trying to wake it by kicking it," he replied.

"People see what we did and understand that you can live in a different way, you can be braver."

Suddenly Vorotnikov is on his hands and knees on the rain-slicked pavement showing me how he crawled into one Moscow police station which had a reputation for racism.

"The officers there treated local immigrants like animals, so we got down on all fours and turned their station into a farmyard. Then we formed a human pyramid and began reciting avant garde poetry."

The police looked on dumbfounded, confused by the fact that the activists arrived with cakes, tea and a huge portrait of the Russian president.

"They were desperate to get rid of us," said Natalia, "but at first, they thought we were officials from the Kremlin".

A few days later, she emailed to say that both Oleg and Lenya had been arrested on charges of hooliganism for overturning the police cars.

They will be held in pre-trial detention for at least two months and Oleg wrote that his cell is freezing and dark as a coffin.

She tried to send him food and warm clothes but the parcel was rejected. Apparently the St Petersburg police do not share Voina's sense of humour.

But 1,300 miles away, the world's most famous graffiti artist did get the joke, and decided to help his fellow satirists.

And from St Petersburg Natalia Sokol - aka Little Goat - emailed her gratitude: "This will be an enormous boost to the guys behind bars, and will help their morale."

Banksy's gesture may or may not contribute to their release from prison, but his involvement has certainly thrust a group which has long been notorious in Russia onto a global stage.

- Published6 March 2012

- Published19 November 2010

- Published11 October 2010