Uncertain future for Hungary sludge victims

- Published

The torrent forced the evacuation of hundreds of residents.

A young man leans over his microphone to prepare the midday news on 103 FM, the Voice of Devecser. It is a few minutes to 12 and there's time for one more song.

"Well I'm standing by a river but the water doesn't flow. It boils with every poison you can think of," sings Chris Rea.

The words ring true in a town catapulted to global fame by disaster - the massive spill of red sludge from the aluminium works in nearby Ajka, on 4 October.

The radio station is broadcast from the Catholic vicarage, one of many initiatives which are helping the 6,000 or so people of this town step beyond the wave of destruction which engulfed them.

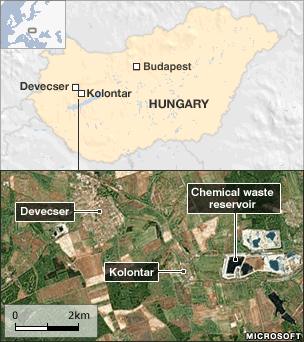

How the reservoir at the heart of the disaster looks now

The radio station is a mess of mixing desks and screens, and cups of coffee growing cold as presenters fade up the microphones, with only a fraction of a second to spare.

I tiptoe out, to visit one of the church's other projects, four families made homeless by the catastrophe, who have been given temporary accommodation in a church-owned block of flats.

'Going to change'

"It wasn't the sludge which destroyed our house, but the rescue effort," says Zsuzsanna Riba, who has lived in a small church flat with her mother and son, Marton, since the beginning of November.

A series of aid initiatives have offered help to the victims

The sheer weight and frequency of army trucks, fire engines, street-sweeping vehicles, and, finally, heavy good vehicles moving the sludge scraped up from peoples' yards and gardens in the aftermath of the influx, caused the corner wall of their old house partially to collapse.

"It's hard to explain to a child that everything he's known in his short six years is going to change now. And it was hard for my mother, and for me too. We're like everyone here - just trying to come to terms with what has happened to us," says Ms Riba.

As she only rented, but did not own her home, she stands little chance of compensation.

The future is cloudy, but the stove is giving out a good heat, as she busies herself with her mother, laying out toys before her son returns from kindergarten.

Teddy bear

Before the disaster, only a cyclist or an elderly person with a frame might have noticed the gentle gradients of Devecser, but now they mark off the doomed, lower reaches from houses on the higher ground which were hardly touched by the tidal wave of sludge.

Each tree in the park carries a mark showing the depth of the sludge

Tibor Nagy takes me to see the ruins of his home in Kinizsi street.

He at least has been offered what he calls a "correct" sum for his house.

"But it doesn't take into account the years of work on it. Every penny we saved was plunged into the workshop, insulation for the roof, the heating system."

In his daughter's bedroom, there's still an embroidered teddy bear on a floor cracking with dried mud.

Like 200 other homes in Devecser, this one will have to be bulldozed.

'Tidal mark'

Though the mud only came up to ankle height, its caustic ingredients continue to eat away the foundations. There are plans to turn to whole lower part of the town into a memorial park.

"Those who had most, lost most," says Tibor, though he doesn't begrudge the advantages that some of the poorer, mainly Roma families in Devecser stand to gain.

"If someone didn't have a bathroom before, let them at least have a bathroom now," Tibor told a recent meeting in the town hall.

"So that at least something good could come out of all this."

I meet his daughter Viktoria, 14, in the primary school. She's a good pupil, always has her hand up in the geography class.

The school is kept spick and span by cleaners who constantly wash down the floors. Air ventilation machines hum and hiss in every classroom.

Destitute families still live in the old music school building. In the Castle park behind, where the pupils used to play, each tree carries what looks like a tidal mark, or the anti-fouling paint on the hulls of boats.

But the only tide which ever flowed through here was from the burst dam.

"I'll miss the garden even more than the house," admits Viktoria.

"There was a tree I always used to climb, and favourite places to play."

All four members of the family were keen archers.

Red planet

Now the only place they have to practice is in the narrow confines of Viktoria's grandmother's backyard.

The art teacher in the school proudly produces recent children's paintings and drawings.

Many feature a remarkable intervention from the red planet Mars.

Martians watch the disaster in Devecser on television and send help, including astonishing mops and brushes lowered from space-ships.

Little green men are depicted working alongside rather more predictable-looking firemen and soldiers and ambulance staff - from the red planet which Devecser, and neighbouring Kolontar, became.

'Solidarity'

Some of the best of the paintings are now on display in the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest.

"We've been overwhelmed by the help we've received," says Ilona Eszterhayne Fatalin, the school principal.

"It is often initiated by children in other schools, who get their teachers involved.

"Hundreds of schools have sent us messages of support, pictures, equipment. I've never witnessed such solidarity, in my whole life."

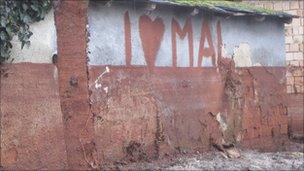

Graffiti is daubed on a wall, expressing ironic affection for the aluminium works behind the sludge

Even as we speak, more photocopying machines arrive from a school in Budapest.

Down the road in Kolontar, the village first struck by the disaster, earth-moving machines take advantage of a sudden mild spell in an otherwise cold winter, to start clearing the ground for the first new buildings in the village.

Twenty-one homes for those who have decided to stay - at the highest point in the village.

Down in the valley, by the Torna stream, it is hard to imagine that houses stood here, less than three months ago.

The ground has been levelled. Half the village has simply disappeared.

And in the gaping hole in the storage lake, where the disaster happened, protective barriers zigzag back towards the village.

There are plans to plant fast growing trees, a forest for renewable energy, on agricultural land that can never be used for food production again.

The first saplings will be planted in the spring.

- Published12 October 2010

- Published8 October 2010

- Published7 October 2010