France expands nuclear power plans despite Fukushima

- Published

With dwindling fossil fuel supplies, France is increasingly reliant on its nuclear power plants which now provide it with three-quarters of its electricity

In the aftermath of Japan's nuclear crisis at Fukushima, some European nations are rethinking their atomic plans. But France, home to 58 of 143 reactors in the EU, remains nuclear energy's champion, and plans not to retire its power stations but to expand them. Emma Jane Kirby examines why.

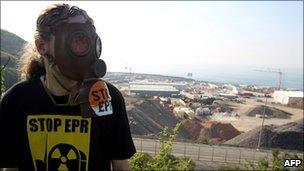

For many tourists visiting the tranquil north Normandy coast, the giant EPR reactor at Flamanville is little more than a lamentable industrial scar on a rather beautiful landscape.

But to the French government, Flamanville's European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) is the embodiment of the future.

Following the disaster at Japan's Fukushima nuclear power station - which was heavily damaged by the deadly 11 March quake and tsunami - President Nicolas Sarkozy announced there would be an audit of all nuclear facilities.

But he added firmly that France would not be rethinking its nuclear energy policy as neighbours Germany, Italy and Switzerland have.

Unlike Germany's reversal of policy on Monday that will see it phase out the country's 17 nuclear power stations by 2022, Mr Sarkozy said France was confident that nuclear energy was safe and it was "out of the question" to end nuclear power.

Sceptical public

The EPR being constructed in Flamanville is marketed as the most secure power station yet.

Anti-nuclear protesters have made their thoughts about the Flamanville expansion abundantly clear

It is built by EDF, a company which is 80% owned by the French government.

The system is organised into four sub-systems (current plants in operation only have two), each located in separate rooms away from the reactor building.

Simultaneous failure of the systems is regarded as almost impossible; the idea is that if an incident were to occur on one of the systems, the reactor could continue to operate safely during repairs, as at least two other systems would remain available.

In the event of a meltdown, the core would be isolated by the reactor building's dual-wall containment which has one wall in pre-stressed concrete designed to withstand significant increases in pressure, and the second in reinforced concrete, known as the concrete shell.

But many French people - including Didier Anger, an anti-nuclear campaigner and former MEP - are not convinced.

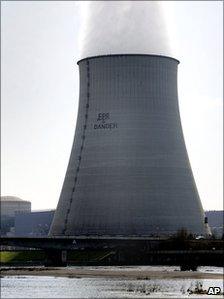

Fukushima was heavily damaged by the 11 March quake and tsunami

"That's just propaganda," Mr Anger told the BBC at his home a few miles inland from Flamanville.

He pointed to the strong ties between EDF and the French government and asked how we could trust the government's word about nuclear safety when it owns such a massive stake in the company that builds the reactors? It was all, he insisted, the "same club".

"France claims to be a democracy," he laughed. "But in terms of the nuclear industry we are yet to prove that!

"A few weeks ago, after Fukushima, the current director of our nuclear safety authority announced in front of MPs that perhaps we should stop the EPR reactor to look at any possible problems.

"A few hours later he was made to back-pedal... he was silenced... because the power of the old boys' network is formidable in France."

Stress tests

Two years ago, cracks were found in the concrete base of the reactor dome at Flamanville and welding proved to be sub-standard. Addressing those safety issues has meant the project is now at least two years behind schedule and way over budget.

This week, European nuclear watchdogs must start safety checks - or stress tests - on their nuclear facilities to make sure they could withstand an earthquake or tsunami like that at Fukushima.

Although a 9m (30 ft) wave is unlikely on the North Normandy coast at Flamanville, Prof Jacques Foos, one of France's most respected nuclear scientists, says all precautions must be taken.

"The accident at Fukushima proved completely extraordinary events can happen," he told me. "So what would happen if a giant wave did hit one of our nuclear power plants? We need to check that out.

"I'm not saying we need to think about every eventuality such as what would happen if we were struck by a meteorite... but I am saying that when we build nuclear power plants now, we have to think the unthinkable."

Major export

The high-tech EPR reactor at Flamanville has been designed to withstand disasters such as a plane crash - but older reactors will not have such sophisticated security systems.

Claude Birraux, an MP with President Sarkozy's governing UMP party, has been chairing the official French parliamentary inquiry into the Fukushima accident, and hopes that the EU stress tests coupled with the separate French audit will help to reassure a nervous French public.

Critics say businesses are scared off by the EPR reactor

"There will be a review made by the safety authorities and if one nuclear power plant is not able to answer to those questions (set by the EU), it can maybe be shut down," he said. "Maybe."

Nuclear technology is one of France's major exports.

Three years ago, France struck a deal with the UK to build four new EPR reactors in Britain but in December 2009 it lost a $40bn (£24bn) reactor deal with Abu Dhabi amid recriminations that it was too costly.

President Sarkozy insisted that the deal was lost because its high safety standards drove up the cost. Professor Jacques Foos hopes that in a post-Fukushima world its "safety first" EPR reactors will bring in more business for France.

"We will see a boost in sales now," he said confidently. "Because who would baulk at paying for safety these days? You can't have a reactor these days that's thought of as being too safe."

A boost in sales should result in a boost in jobs but that's not an argument that holds much sway with anti-nuclear campaigner Didier Anger. Building on a second EPR reactor on the Normandy coast at Penly begins next year but Mr Anger doubts it will boost employment.

"In Flamanville, we thought the EPR would bring a lot of employment... but 50% of the workers are from Poland or Romania, or at least not from here," he complained.

He pointed to the high 9.7% unemployment rate in the Cherbourg area and asked me why I thought the jobless total was so high.

"It's because a lot of businesses are scared off by the EPR reactor," said Mr Anger. "They think what if there was an accident? The exclusion zone would be 20km [12 miles] or more. That's no good for business… so they don't set up here."

Nuclear landscape?

But if France is to make more sales with the EPR reactor, who will the new customers be when most of Europe appears to be pulling out of the nuclear energy game and mothballing their old reactors?

Could nuclear technology be sold to countries which simply aren't ready to deal with the potential risks?

Memories of the disaster at Chernobyl linger in France quarter of a century later

MP Claude Birraux insists that France will only sell nuclear technology to responsible countries.

"There are three rules: safety, safety and safety, whatever the cost," he said. "You need to have regulation, legislation and you need an independent safety authority... otherwise no... you can't have it."

France began developing its civilian nuclear programme as a response to oil shortages in the 1970s. With dwindling fossil fuel supplies, the country is increasingly reliant on its nuclear power plants which now provide it with three-quarters of its electricity.

Nuclear energy, said Claude Birraux, was essential for "French independence".

With 58 nuclear reactors already in operation here, sites like Flamanville look likely to be part of the French landscape for many years to come.

- Published25 May 2011

- Published3 May 2011

- Published25 April 2011

- Published15 March 2011

- Published18 March 2011