Italians find voice and punish Silvio Berlusconi

- Published

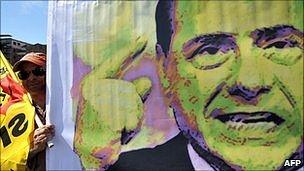

Opponents used new media to bypass Mr Berlusconi's dominance of TV

Italians have firmly rejected Silvio Berlusconi's plans to revive nuclear power and his right to skip his trial hearings, in a popular referendum which the prime minister had urged voters to boycott.

Two weeks after the people of Milan, Naples and other towns and cities gave him a bloody nose in elections for mayors and local councils, Mr Berlusconi could be forgiven for thinking he has just been hit by a runaway train.

Italian voters seem to have learned the lessons of the local elections. In particular, they may just have rediscovered some faith in their political system - if not in their ageing political leaders.

It has become de rigueur to say it - but the new media have played a key part in this.

The lesson was there for all to see in Milan during the local elections. Across town, images of Mr Berlusconi's candidate, Letizia Moratti, were splashed across billboards with photoshop-perfected portraits of a woman at the top of her game.

Her party leader himself used his domination of Italian TV to get himself a blitz of relatively tame prime-time interviews.

It did not work. The still fledgling new left used Facebook, Twitter, emails and blogs. Their victory was not just a protest vote - it was a victory of new media over old, in a country where, as everyone knows, the old media are dominated by one man and his family.

Church influence

It was the same before the referendums. Across cyberspace a new generation of Italians - the 30-somethings forced to live with their parents because they cannot get a steady job and cannot afford a home of their own - were texting, Tweeting and emailing each other encouragement to vote.

Their opponents, too, made full use of social media, to justify - for example - a voter's right to abstain from the electoral process.

If the new media look like game-changers, the oldest team in town - the Roman Catholic Church - has been influential too.

Milan's Corriere della Sera newspaper featured a photograph of the city's archbishop, Dionigi Tettamanzi, leaving a polling booth after casting his vote on Sunday.

He was not alone - and he and his fellow bishops did not just vote. They spoke out - sometimes forcefully - on the issues on which Italians faced a choice at the polls.

Pope Benedict XVI himself subtly touched on one of the key issues on the ballot paper when he referred obliquely to March's tsunami in Japan and the risks of a reliance on nuclear power, going on to demand - more trenchantly - a new way of life that respected the environment and protected "the legacy of God's creation".

Failed gamble

The past two weeks may yet come to be seen as the moment that ordinary Italians realised that they could indeed have a say in the way their country is run.

The current crop of politicians - Italy's gerontocracy - remains trapped in the post-war division between left and right, with its provincial loyalties to family, city and region.

Their successors need not be. They are well-travelled - in reality as well as in cyberspace - and are familiar with different societies and different ways of doing politics.

Italians seem to have rediscovered the referendum. Ignored, and considered almost a joke for years, it could now - in tandem with the new media - have given Italian democracy a new lease of life.

Mr Berlusconi and his key ally, Umberto Bossi of the regionalist Northern League, made clear their contempt for the referendums - and encouraged their supporters to stay at home, confident in the knowledge that the vote would count for nothing if fewer than 50% of Italians bothered to turn out.

The old guard's gamble failed. The disenfranchised young have had their say. They may just have got a taste for it.

- Published14 June 2011

- Published30 May 2011

- Published11 June 2011

- Published15 March 2011

- Published12 September 2011

- Published6 August 2010

- Published21 July 2011

- Published23 March 2011