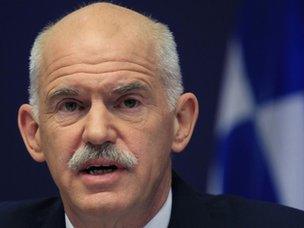

Profile: George Papandreou

- Published

Mr Papandreou has been prime minister since 2009

Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou, leader of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (Pasok), is the scion of Greece's premier socialist dynasty.

The son and grandson of two former prime ministers, his surname harks back to old times.

But the 59-year-old has recently found himself in uncharted waters - battling for his political survival as the nation wrestles with a debt crisis and its future in the eurozone.

Critics say his decision to call a referendum on a EU rescue package - and its swingeing public spending cuts - was a dangerous gamble.

One Pasok MP left the party and several others threatened to follow suit, opposing an initiative that threw Greece into political turmoil to match its financial woes.

The referendum plan was quickly withdrawn, but Mr Papandreou had to face a vote of confidence in parliament that he had earlier called. His vulnerable position in parliament meant the outcome of the vote was never certain, but Pasok narrowly won with 153 votes to 145.

However pressure on his position remained, and only two days afterwards he agreed to step down as part of a deal to form a government of national unity to push through the EU deal.

For Mr Papandreou, it is a far cry from the heady night in October 2009, when he swept to power promising to revive the country's ailing economy with a 3bn-euro ($4.4bn: £2.7bn) stimulus package.

Speaking in Athens after Pasok dealt the conservatives one of their worst electoral defeats, he promised to transform "to change the country's course into one of law, justice, solidarity, green development and progress".

Two years on that vision remains unfulfilled.

It quickly became clear that Greece's finances were in a parlous state, with a gaping budget deficit and soaring public debt.

Correspondents said that voters had preferred Mr Papandreou's promised stimulus package to the programme of austerity proposed by the beaten Prime Minister Costas Karamanlis.

Yet it is the Pasok leader who has found himself promoting waves of austerity measures that have prompted widespread protests - even as the confidence of Greece's international lenders remains fragile.

Political dynasty

Mr Papandreou replaced former Prime Minister Costas Simitis as Pasok's leader in 2004.

Despite the personal popularity of its new leader extending beyond grassroots socialists, Pasok lost that year's general elections.

Pasok had ruled Greece for almost 20 years but its old guard was tainted by allegations of sleaze and complacency. In opposition, Mr Papandreou pledged to clean Pasok's house.

In September 2009 he said: "If Greece had gone through a very normal political life, I may have not been in politics.

"But just the fact that I lived through huge upheavals and very difficult struggles and polarisation and the barbarism of dictatorships - that made me feel that we had to change this country."

George Papandreou senior was prime minister of Greece twice.

His son Andreas was exiled from Greece in 1939 and went to the US, where George junior was born to an American mother in 1952.

The future prime minister attended schools in Illinois, Sweden and Canada and received degrees from Amherst College, the London School of Economics and Harvard University.

He speaks English, Greek and Swedish.

He returned to Greece after the restoration of democracy in 1974 and became involved with his father's party.

'Calm and thoughtful'

Rising through the ranks of Pasok, he was elected to parliament in 1981, the same year his father was elected prime minister.

After a number of ministerial posts, George Papandreou was appointed foreign minister in 1999. He was also the minister responsible for the successful bid for 2004 Olympic Games.

As foreign minister, he helped ease long-standing tensions with neighbouring Turkey and improved relations with old rivals Albania and Bulgaria.

Mr Papandreou was also closely involved in the efforts to end the division of Cyprus ahead of the island joining the European Union in 2004.

In the end, the Republic of Cyprus did join the EU, but the Turkish-speaking north, not recognised internationally, remains outside.

Before the 2009 election, opponents had always belittled Mr Papandreou as lacking leadership skills.

But until the turmoil of his final week in office, he was considered a calm, thoughtful and diplomatic politician, in contrast to the flamboyant personalities of his father Andreas and grandfather George.

- Published2 November 2011