Crucial vote for Greece

- Published

- comments

Politics is in the bloodstream of the Papandreou family

Democracy has deep roots in Athens.

Some 2,500 years ago in what was then a city-state, they began the experiment of arguing, debating, and voting.

Today all the same traits continue - deal-making, rifts, alliances made and broken, horse-trading and betrayals. It is the stuff of politics and democracy and was on full display on Thursday.

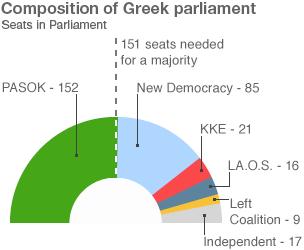

Late on Friday but more probably in the early hours of Saturday, Greek MPs will decide the immediate fate of Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou. A confidence vote will be held and it will be close.

When he announced his intention of holding a referendum on the EU's bailout package, many in his own party were horrified. Even his finance minister did not think it necessary.

The markets tumbled and George Papandreou was summoned to Cannes for a dressing down by the masters of the eurozone, France and Germany. As a result he could no longer count on the support of his own party in a confidence vote.

And then the manoeuvring began.

'Looking for an exit'

In order to strengthen his chances the prime minister decided to scrap the referendum - according to his office. He said it was no longer necessary because the opposition had now come behind the EU rescue package.

The opposition said they had already backed the deal on 27 October. As a result of the U-turn some MPs from his own party who had signalled they may have voted against him are now coming back into line. George Papandreou may yet survive.

He has also indicated - through his office - that whether he wins or loses talks will begin on forming a government of national unity.

Certainly such an outcome would be welcomed in Brussels. They see political divisions in Greece as being at the heart of the problem. But the opposition would not countenance any coalition with George Papandreou at the head of it. They want snap elections where they are likely to emerge as the largest party.

Some, like Constantine Michalos of the Athens Chamber of Commerce, external, question how long Papandreou will relish the political fight.

"I think he is looking for a dignified exit," he said. "And I think in all certainty within the next 10 days we will have this transitional national unity government that we need in order to safeguard the interests both of the Greek economy and of the European economy as well."

Perhaps. But politics, power and patronage are in the bloodstream of the Papandreou family. So like with most politics, this is at heart a battle for power.

Change of mood

Perhaps the most significant legacy of this tumultuous week has been with the people.

I cannot prove it, but the tough statements from the leaders of France and Germany have had an impact. People realise they could be forced to leave the eurozone and most Greeks don't want that. They treasure being part of mainstream Europe.

On the streets it is possible to detect a slight change of mood. Yes they are weary, frustrated and angry with austerity but, as one newspaper editor said to me, "they looked into the abyss and haven't liked what they've seen."

The EU has been piling on the pressure. Officials have admitted there is contingency planning for Greece to leave the euro. A line has been crossed. A taboo broken.

When President Sarkozy - brimming with irritation - said: "If you don't abide by the rules you have to leave the eurozone," no one could fail to grasp that the patience of Europe's leaders with Greece had snapped. No one wants Greece to leave, but the 16 other members won't be held hostage by Athens either.

The British Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne said: "We can make sure the world is prepared for any outcome from Greece.. any eventuality that might befall Greece... Britain prepares for all contingencies - we must make sure Britain is as safe as possible... We are also prepared for whatever the eurozone throws at us."

That said, there is a downside to the referendum being scrapped.

The sensitive issue of outsiders dictating policy to Greece will remain unresolved. Most of the population will still resent the cuts and spending increases. It will prove almost impossible to meet targets.

Ten years of austerity, which lie ahead, will test the fabric of this society. Growth will remain elusive and a basic truth will remain unanswered - that the German and Greek economies are so different it is hard to see them successfully being part of the same currency union.

So the leaders meeting in Cannes have shown their harsher face.

At the same time they are about to boost the firepower of the IMF. The British position is that they want the fund strengthened, but not to bailout the eurozone.

But that is precisely what some other countries want. They see the IMF as a key weapon to be used if Italy and Spain get into difficulty.

It is hard to see how the UK will ensure that any increased contribution does not end up propping up eurozone countries. There is a very real prospect that despite all the denials the UK will end up contributing to the bailout via the IMF.

But the story of the week so far is not the machinations in Greece; it is that the eurozone's leaders accept that it may be better for some countries to leave.