Russia's opposition ballot: The country's other elections

- Published

Leonid Volkov has a team of 25 preparing for the ballot

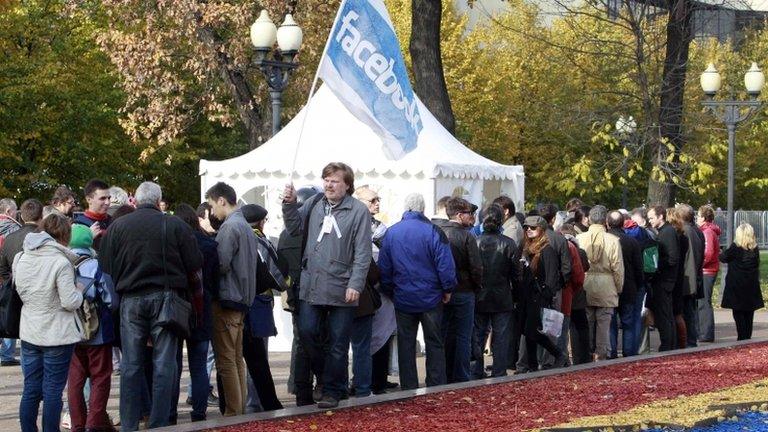

Russia's new opposition movement has become so fed up with unfair elections, that it has decided to organise its own.

More than 150,000 people have registered for the vote, and the numbers are still rising.

The election this weekend will choose a 45-member opposition Co-ordination Council (CC) whose job will be to try to harness constructively the growing mood of dissent in Russia.

The project is being run from an anonymous-looking office block in Yekaterinburg in the Ural mountains, some 2,000km (1,240 miles) from Moscow.

What was a team of seven has grown to 25 - programming the election computers, and checking the identities of people registering, to prevent multiple voting.

They are a young, enthusiastic team who look like something out of a Starbucks commercial - sitting cross-legged and drinking coffee as they worked on their laptops.

The opposition's central election commission is led by Leonid Volkov, a computer entrepreneur from Yekaterinburg, and a passionate democrat and liberal activist.

"We need good opposition politicians for Russia," he explained.

The Co-ordination Council, he suggested, would generate long-term projects that might change public attitudes.

Internet record

The project has become one of the biggest internet elections ever held, though voting at polling stations will also be possible.

It was a response to the growing concern in opposition circles that they did not know what to do next after the mass street protests in Moscow this past year.

On the biggest marches the number of participants in the capital probably topped 100,000 but since Vladimir Putin was returned to the presidency, the opposition has lacked direction.

This election is an attempt to choose a focused leadership and to spread the opposition's message out beyond Moscow. Of those who have registered to vote, around 65% are outside the capital.

Mr Volkov said the projects had been a success for politics in the regions, used to seeing "everything decided in Moscow".

Over the last 12 years Russia's real opposition parties have struggled against the Kremlin, which has at various times banned them and refused to register them, and locked up the only oligarch prepared to fund them, Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

The only opposition parties allowed to survive have been those giving broad support to the status quo. The Kremlin called it "managed democracy", and at times it has appeared to be stage-managed by Vladimir Putin himself.

So opposition activists outside Moscow have had a particularly lonely time, but some have persevered.

'Huge leap'

In Kirov, around 1,000km north-east of Moscow, lives Anton Dolgikh, a 35-year-old lawyer who describes himself as "a rather independent person".

He struggles against the corrupt, local bureaucracy in his city of half a million people at every opportunity. When he argued with the builders of his apartment block his car was set on fire.

He admits that at times it has been a lonely fight but he has been re-energised by the protests after last December's rigged parliamentary elections, which even spread to Kirov.

"If in my sleepy town 2,000 people come into the streets," he told me, "it means that something has changed and it has changed dramatically. The point of no return has passed. We can't go back."

So he stood for the CC elections, even travelling to Moscow for a live debate on Dozhd - the country's most opposition-friendly TV channel, available only on cable, satellite and the internet.

Leading protester Alexei Navalny is among the candidates

Although he knows his chances are slim against the well-known opposition leaders in Moscow, he said he felt compelled to stand.

"Living in Russia, for the last 10 years, of course the living is better than it was in the 1990s," he added. "But we don't have freedom right now, we don't have law, we don't have courts.

"The time has come to make a leap, make the next huge leap. I want my country to be a democratic country, with the rule of law, with democratic procedures, with free elections and with no thieves in power.

"And I can't stand away from problems that happen in my country. I think it's my obligation to get in that struggle."

'Healthy competitition'

That struggle will not be an easy one. In the March presidential poll a fellow activist filmed people queuing up to receive 500 roubles (£10; $16) each to vote for Vladimir Putin.

Only a few hundred people in Kirov have registered to vote in the opposition election. Among them is Eduard Patrushev.

So far he has been a reluctant supporter of Russia's Kremlin-friendly parties but he believes the lack of choice is strangling democracy in the country so he will be an enthusiastic voter in the opposition elections this weekend.

"People still believe we live in a democratic country," he said.

"But we need an opposition to provide healthy competition, so that new leaders can emerge. The kind of leaders that the voter needs - ones that have our interests at heart, not vested interests. Russia needs an opposition like it needs oxygen."

Or as Anton Dolgikh put it in English: "Many of people, if not all people with whom I speak on the streets ask one question 'If not Putin then who?' Only if we have free elections we will have new politics, and then people will see if not Putin then who."

- Published23 October 2012

- Published16 February 2024

- Published17 October 2012

- Published17 August 2012

- Published17 March 2024