Could the BBC have done more to help Hungarian Jews?

- Published

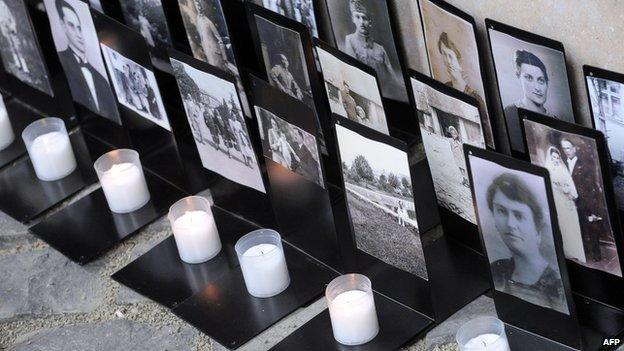

Nearly half a million Hungarian Jews were killed in a matter of weeks in 1944 soon after German forces invaded their country. Mike Thomson reveals how the BBC's Hungarian Service could have warned them of their likely fate in the event of such an invasion, but did not do so.

In 1942 the BBC European Service was the front line in a propaganda war. The language services were broadcasting all over the continent to help the Allied war effort and convince those listening that the Allies were winning.

The BBC's foreign broadcasts at the time were not independent as they are now. They were being overseen by an organisation called the Political Warfare Executive (PWE). It ran the battle for European hearts and minds from the floor it occupied in Bush House, the World Service's then headquarters in London.

That battle was particularly delicate in Hungary. Historically sympathetic to Germany, the Hungarians were allied with them but not fully settled in the Nazi camp.

The PWE - through the BBC broadcasts - sought to win over Hungarians and foment trouble in their alliance with Germany. It hoped to encourage resistance and bog German troops down in Hungary as an occupying force.

And to this end the BBC broadcast every day, giving updates on the war, general news and opinion pieces on Hungarian politics. But among all these broadcasts, there were crucial things that were not being said, things that might have warned thousands of Hungarian Jews of the horrors to come in the event of a German occupation.

A memo setting out policy for the BBC Hungarian Service in 1942 states: "We shouldn't mention the Jews at all."

It was brought to my attention by Professor Frank Chalk, Director of the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies at Concordia University in Canada, and was written by Carlile Macartney, Oxford academic, ex-MI6 officer and the Foreign Office's top adviser on Hungary. And he was also on air as the BBC's top broadcaster on the Hungarian Service.

Macartney believed that to champion the Jews would alienate the majority of the Hungarian population who at that time, he argued, were anti-Semitic. Given that British propaganda directors wanted to draw German troops into Hungary as an occupying force, the argument was that anti-Semitic Hungarians wouldn't help the Allies if they seemed too pro-Jewish.

Hungary was home to one of Europe's largest Jewish populations, comprising around 750,000-800,000 people. They were subjected to anti-Jewish laws and widespread anti-Semitism among the wider population - and thousands of Jewish Hungarians died after being forced to serve in labour battalions on the war's eastern front.

Yet the Hungarian government had resisted Nazi demands to hand over its Jewish population, and it was largely intact until 1944.

Taken off air

From December 1942 the British government, the PWE and the BBC Hungarian Service knew what was happening to European Jews beyond Hungary, and the very likely fate of the Hungarian Jews if the Germans invaded.

No one could have expected the staff at the Hungarian Service to predict the Germans' March 1944 invasion of Hungary. But PWE documents do show that it was the aim of some of its broadcasts to provoke such an invasion.

Either way, the Hungarian Service continued following Macartney's advice and did not broadcast information about the exterminations taking place in Poland and elsewhere.

And this was despite increasing unease about Macartney. Internal BBC and British government memos show senior figures in the propaganda war querying Macartney's role, attitudes and status.

He was also subject to a campaign by Hungarian exiles criticising the BBC's approach. They were worried that he had become too sympathetic to the Hungarian government, too willing to overlook its pro-German positions.

Eventually, Macartney became so controversial that the PWE chief Robert Bruce Lockhart demanded that he be temporarily taken off air.

And yet his policy of silence on the Jews was followed right up until the German invasion in March 1944. After the tanks rolled in, the Hungarian Service did then broadcast warnings. But by then it was too late.

The German occupiers instigated the Final Solution in Hungary, and nearly half a million people were killed in a matter of weeks by the Nazi extermination operation at its most chillingly efficient.

The European Service as a whole is credited with transmitting warnings of the fate of the Jews. By 1943, the BBC Polish Service was broadcasting about the exterminations. So could warnings from the BBC Hungarian Service in 1943 have helped Hungarian Jews?

The question of what Hungarian Jews already knew has become a vexed historical issue.

"Many Hungarian Jews who survived the deportations claimed that they had not been informed by their leaders, that no one had told them. But there's plenty of evidence that they could have known," said David Cesarani, Professor of History at Royal Holloway, University of London.

"The destruction of the Jews in Europe really moves into a high gear in the summer of 1942, with deportations from all over Europe, from the great concentrations of Jewish population in Poland, to the extermination camps. That is when news begins to filter into Hungary.

But they did not know that the Germans would occupy Hungary and bring with them the machinery of destruction. All of this was beyond their most horrible nightmares, and people faced by such nightmares tend to go into denial - and that I think is what many Hungarian Jews did."

Tony Kushner, Professor of the History of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations at the University of Southampton, argues that: "One of the major and most painful controversies from the survivors is "we didn't know". Now, we can dispute that to some extent."

"But there is a difference between knowing and believing, and had there been more attention to what was going on beyond its borders, perhaps that inertia of Hungarian Jews, but much more importantly of the Hungarian population as a whole, may have been to some extent challenged," he adds.

A 'fantasy'

The Document programme spoke to Marianne and Yves, two Hungarian Jews who lived in Budapest during the war. Today, they remember listening to Macartney's broadcasts and told us that at the time they thought of the BBC as a "drop of water in the mud".

Yves, who survived deportation to a labour camp, recalls: "I didn't know about Auschwitz. I knew there were deportations, that there were concentration camps, but this extermination, the use of gas chambers? I don't remember. That comes after the war."

If, with the backing of the PWE, who were controlling their broadcasts, the BBC had transmitted warnings throughout 1943 telling the Jews of Hungary of the extermination programme unfolding beyond their borders, might lives have been saved?

Tony Kushner argues that: "Up to 200,000 Jews did survive, which is a fraction of the 800,000 who were present in 1944. But it's still an indication perhaps that more could have been saved inside Hungary."

And Frank Chalk argues that at least a few thousand Hungarian Jews could have been saved. They had no inkling of the annihilation of the Jews elsewhere, in his view, but "the opposite might have been the case if the BBC had warned them."

"Then they would have hidden, they would have sought escape routes, they would have fought… Warnings from the BBC Hungarian Service to the Jews of Hungary and calls on the Christians of Hungary to support the Jewish population by offering sanctuary, false papers, help escaping to Romania, would have been of great significance."

But David Cesarani is unconvinced: "This is a fantasy. It wasn't the job of the BBC to warn Jews that the Nazis were coming to get them. The responsibility lay elsewhere. The BBC was doing everything it could to help win the war."

"Some could have built bunkers, hideaways, some could have tried to get false papers. But we're talking about 750,000 people, surrounded by a hostile population, by countries either Allied to the Nazis, or occupied by the Germans, there was nowhere to hide, nowhere to run," he adds.

Whatever later became clear about what the Hungarian Jews did or did not know about the extermination programme unfolding beyond their borders, the question remains: given that the PWE and BBC did know, should they have abandoned Macartney's policy and mentioned it in broadcasts to Hungary - whether or not it would have done any good?

Then again, can such a judgement ever be fairly made in times of peace - so many decades later?

- Published29 June 2012

- Published22 July 2012