Groningen gas fields - the Dutch earthquake zone

- Published

Klaas Koster and Jannette Schoorl show a crack in the wall of their home in Middelstum

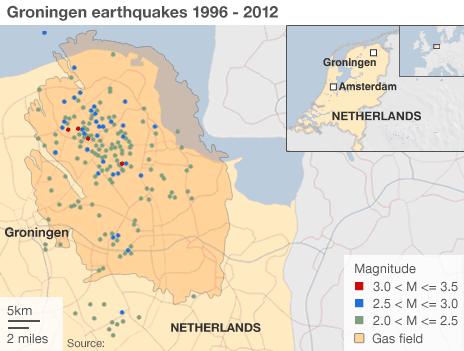

As earthquakes become more intense and more frequent in the north of the Netherlands, there is mounting pressure on the government to reduce the amount of gas being extracted there.

It is a curse for thousands of inhabitants having to cope with the effects of living amid the Groningen gas fields - the largest in Europe.

There exists a consensus among all parties - including the gas companies - that the process of extracting the gas is causing earthquakes, but the country is thriving on the proceeds.

In 2012 the Dutch government made about 14bn euros (£12bn; $18bn) from the Groningen gas fields. Without these revenues, the Netherlands' deficit would be similar to that of crisis-struck Cyprus (6.3%).

"It comes rumbling towards you, louder and louder and louder," says Daniella Blanken, who runs the Groningen Ground Movement.

"Everything starts to shake. It ends with a bang, like a massive weight dropped on the house. Boof! And that is frightening, really really frightening."

She is driving us through a newly built neighbourhood. It is Dutch-style suburbia: a canal running down the left side of the street. But Middelstum is one of the worst-hit areas.

What percentage of these homes here has been affected? "At least 60% but the old ones are worse," she says.

Cracked steps

Approximately 60,000 homes lie within the earthquake zone. The gas companies are dealing with about 6,000 damage claims.

Earlier, at Ms Blanken's cosy kitchen table, she struggled, voice cracking with emotion to explain their desperation: "We want them to put our safety on top of everything, but they don't, they really don't.

"The government is meant to protect its citizens," she says, then pauses before adding: "We don't feel protected."

We pull up outside a flower-festooned farmhouse. Number 13. Home to Klaas Koster and Jannette Schoorl.

A measuring device reveals a jagged split about 7cm (2.7in) wide running through a concrete step and up the side of the house, as though lightning has struck and left an ugly, indelible mark.

"The experts told us this part of the house is saying 'goodbye'," says Mr Koster.

His tone is jovial, a deliberate effort to cope with a problem residents are powerless to prevent. The floor of the utility room is clearly subsiding. It is an extraordinary concern in a region that lies almost entirely below sea level. This is not a land that can afford to sink any further.

Nor can it afford to give up its gas habit. At the Dutch parliament in The Hague, 200km (124 miles) away, Economics Minister Henk Kamp explains why: "Almost all the people heat their houses with Groningen gas and they cook their meals with Groningen gas.

"It's also important because of the budget of our government."

The Dutch government owns large stakes in the gas fields. While there is sympathy, few are prepared to sacrifice the relative economic prosperity generated by the Groningen gas.

As one car park attendant puts it, "If the Groningers don't like it, they should just move elsewhere."

There is another reason the economics ministry has rejected some scientific recommendations to cut the scale of explorations immediately: contracts.

"We have long-term contracts with other countries," Mr Kamp admits. "And that's also an important point for us."

The government was unable to give an exact value. The economics minister told us they were trying to establish if financial penalties would be incurred by reducing the supply to foreign buyers.

'Nothing excluded'

Groningen gas was discovered in the 1960s. Since then, the Dutch government has reaped an estimated 250bn euros from the sale of this natural resource.

Last August there was a magnitude 3.4 tremor. Higher than any expert had previously predicted, it further sapped the residents' confidence and forced the ministers to commission an inquiry.

"Until now we always knew that earthquakes could occur, now we don't know what the new maximum could be," says Chiel Seinen, who represents the NAM oil company collective incorporating Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Exxon Mobil Corp.

"There is a compensation scheme in place. A million-euro fund? No, there is no limit. People can count on it that we at NAM will compensate them for any damage caused by the earthquakes."

Does Chiel Seinen believe that lives could be in danger? He raises his eyebrows: "You can never exclude anything. If people are in the wrong place at the wrong time…"

And that is the fear of those whose ancestors lived on the land long before the gas firms started shaking it.

The Groningen Ground Movement is currently considering taking its case to the European Court of Human Rights, on the grounds their basic right to live without fear is being violated.

Back on the farm, Mr Koster pours steaming glasses of sweet herbal tea and retrieves a thick pile of newspaper cuttings from a corner - contrasting the scale of the coverage with the level of government response.

He and Ms Schoorl are two of the many people still waiting for compensation. They are tired of fighting to convince the experts, funded by NAM, that the latest cracks were caused by the extractions.

And Ms Schoorl is having trouble sleeping: "We sleep underneath a beam. At night I think, what if there was another earthquake and that beam was to come down on top of us? I hope I will live to tell about it."