Treblinka survivor recalls suffering and resistance

- Published

Samuel Willenberg is the last survivor of the Jewish prisoners' revolt

Wearing a military beret, medals and walking with a stick, 90-year-old Samuel Willenberg led a crowd of people through a clearing in the pine forest, stopping sporadically to point out: "And the platform was here, the trains stopped here."

Nothing remains of Treblinka extermination camp apart from the ashes of the estimated 870,000 mostly Jewish men, women and children that the Nazis gassed and buried underground.

On a bright summer's day, with storks nesting nearby, it is hard to imagine the horror that occurred here.

Samuel Willenberg is the last survivor of the Jewish prisoners' revolt in the camp and he had returned for the 70th anniversary.

In October 1942, aged 19, he was among 6,000 Jews from the Opatow ghetto who arrived by train at Treblinka in Nazi-occupied Poland.

They were told they were at a transit camp and had to undress and shower before being sent onward. In reality, the shower rooms were gas chambers.

As he waited, Samuel Willenberg, the son of a painter, saw a familiar face among the Jewish prisoners.

"The man I recognised asked me: 'Where are you from?' I said, 'Czestochowa' and he said, 'Czestochowa?'

"He said, 'Tell them you're a bricklayer'. In a couple of seconds an SS officer came and called out, 'Where is the bricklayer?' I jumped out and I showed him my father's stained painter's apron I was wearing and that's what convinced him. He sent me to the prisoners' barracks with a kick up the backside. A whole town, three transports of 20 wagons, went to the gas," Mr Willenberg told the BBC.

He was one of about 750 Jewish workers at Treblinka. His job was to sort through the belongings of the people sent to the gas chambers.

"One day I was passing by," he began, his voice breaking.

"On that day, I looked. My little sister had a coat she grew out of. My mother had extended the sleeves with green velvet. This is how I recognised it. I can still see it today."

He pauses, saying he can't go on. The story seems too painful to tell. But then he continues.

"It was then I knew my sisters had come to Treblinka. I understood that I no longer had sisters. I looked, but I didn't cry. I had no tears left, just hatred," he said, wiping away the tears that flowed freely now.

Camp torched

A small group of prisoners was planning to revolt.

The transports had mostly stopped arriving in April 1943. SS commander Heinrich Himmler visited Treblinka in March and afterwards the victims' bodies were dug up so that they could be burnt on huge pyres. The Nazis were hiding the evidence of their crimes. The burning went on through the summer and the prisoners knew that when the work was completed, they would be killed.

On 2 August, with a copied key, they opened the SS armoury, distributed the weapons and set fire to the camp.

A memorial to the many thousands who died now stands at Treblinka

In the chaos of smoke, gunfire and explosions, Samuel Willenberg began to run. Beside him was his friend, a Protestant pastor of Jewish origins, who was known as "the priest".

"The priest suddenly came and we ran together, everyone was trying to escape. I had a machine gun. The priest ran beside me and then he got a bullet in the leg. He fell. He asked me to kill him. I showed him one thing. 'Look back at the extermination camp where your wife and child were killed' and I shot him in the head," Mr Willenberg said.

He ran on to the barbed wire perimeter fence as bullets fired from the watchtowers whistled past.

"I ran to the anti-tank barriers because the barbed wire was already cut. The German machine guns were firing. I darted out and jumped on top of the dead bodies of my friends. They looked like statues.

"Then I was hit. There was some blood and my leg became swollen. But I got through those obstacles. Then I was in the forest and there was a railway line, an asphalt road, more forest and I became crazy. I started yelling, 'hell has been burnt'," he recalled.

Fewer than 70 prisoners escaped and survived the war. After the revolt the Nazis demolished the camp. It was turned into a farm and a Ukrainian family was settled there.

Samuel Willenberg made his way by train to Warsaw where he was reunited with his parents.

"I opened the door to my mum. You can't imagine what it means to return from hell and see your mother and your father. She asked me, where were you? The first thing they both asked was: 'Maybe you saw Itta and Tamara?' I never told them. My mum died in Israel. I never told her that I saw their clothes. I couldn't. I couldn't," he said.

Pursuit of justice

Mr Willenberg joined the Polish underground - the Home Army - and fought against the Germans in the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944, to try to liberate the city from the Nazis.

After the war he married Krystyna, who was saved from the Warsaw Ghetto by Poles. They emigrated to Israel in 1950 but he regularly returns to Treblinka to guide youth tour groups.

On this anniversary Samuel Willenberg began the realisation of a long-held dream. He unveiled a foundation stone for a future Treblinka education centre designed by his architect daughter, Orit.

Most of Treblinka's guards were never prosecuted for their part in these hideous crimes.

Treblinka's commandant, Franz Stangl, was sentenced to life imprisonment in October 1970 following his trial in Dusseldorf.

He died in prison in June 1971. Six years earlier, 10 defendants including deputy camp commandant Kurt Franz were tried in Dusseldorf.

Four were given life sentences, five defendants were given sentences ranging from three to 12 years and one defendant was acquitted.

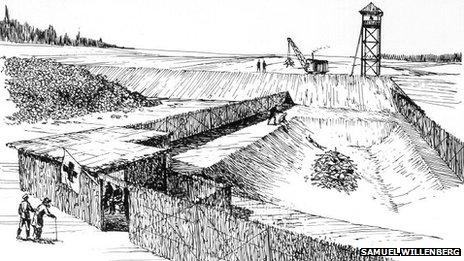

Mr Willenberg's drawing of the Treblinka infirmary shows mass shootings

- Published23 January 2012

- Published19 April 2013

- Published19 April 2013

- Published27 January 2013