Lazlo Csatary: Holocaust questions go unanswered

- Published

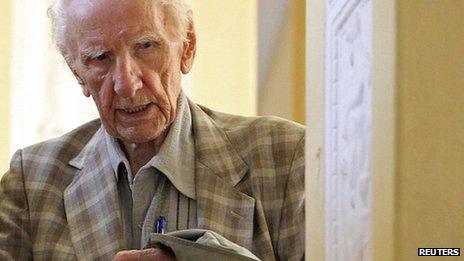

Laszlo Csatary had denied the allegations against him

Laszlo Csatary, one of the last remaining Holocaust war crimes suspects, has died in a Budapest hospital at the age of 98.

He was one of the last men still hunted by the Los Angeles-based Simon Wiesenthal Center and its current president, Efraim Zuroff.

Born in the village of Many, south of Budapest, in March 1915, Csatary served as a police officer in several places in Hungary, lastly in the eastern city of Kosice.

When the Germans occupied Hungary in March 1944, the Hungarian police, gendarmerie and railway employees played an important role in the rounding up and deportation of Hungary's Jews - closely overseen by the Gestapo.

Witnesses, cited at the 1945 trial in Hungary of Csatary's commanding officer, spoke of his particular cruelty in the brickyard on the outskirts of Kosice - of which he was in charge - where Jews were held in May 1944, awaiting deportation.

Csatary allegedly pursued detainees with a dog whip. When the Jews were loaded on to cattle wagons for the journey to Auschwitz, Csatary allegedly ordered even more to be packed into each carriage, despite the infirmity of many of the elderly.

Quiet retirement

His 1948 trial in absentia by a Czechoslovak People's Court - Kosice reverted to Czechoslovak rule in January 1945 - lasted less than a day, with no witnesses in his defence. He was sentenced to death.

In 1949 he arrived in Nova Scotia in Canada, claiming refugee status and then citizenship.

He worked as an art dealer. When the first suspicions of his wartime role emerged he left Canada, in 1997.

He then disappeared from the Nazi-hunters' map only to resurface in Budapest, living a quiet and dignified life in retirement.

Information on his whereabouts was handed to the Hungarian authorities by the Simon Wiesenthal Center in September 2011.

Ageing documents had been prepared as evidence for the trial

Frustrated by the lack of progress in that investigation, the centre tipped off journalists from the Sun tabloid newspaper in Britain, who rang his doorbell in July 2012.

Demonstrations for and against him followed - by far right activists and by Jewish youth associations.

Csatary was placed under house arrest and eventually charged by the Hungarian authorities in June this year.

Slovakia also quashed his death sentence to pave the way for a new trial there.

Proceedings for his deportation to Slovakia were expected to start in September but no date had yet been set for the start of his trial in Budapest.

"In just two years, Hungary has tried and failed to get two war criminals convicted," Laszlo Karsai, Hungary's pre-eminent Holocaust historian and himself the son of a Holocaust survivor, told the BBC.

"Such trials serve no useful purpose - historically, educationally, or politically."

The previous case, of Sandor Kepiro, a Hungarian army office accused of involvement in the January 1942 massacre of Jews and Serbs in Novi Sad, ended with Kepiro's acquittal in July 2011 and his death two months later, aged 97.

Auschwitz was the destination for many Jews transported from Hungary

"While I have no doubt that these two men - Kepiro and Csatary - were war criminals, the sight of them hounded into court evokes only human sympathy," said Mr Karsai.

"After the failure of the 'Ivan the Terrible trial' almost everyone in the Nazi-hunting business, including the vast majority of historians, politicians, and I dare say most Holocaust survivors, realised there were better ways to commemorate the Holocaust."

Society divided

John Demjanjuk, a US citizen of Ukrainian descent, was tried and sentenced to death in 1986 in Israel as a guard named "Ivan the Terrible" at the Treblinka death camp.

That conviction was overturned by the Israeli Supreme Court in 1993. Demjanjuk was later convicted in Germany of being a guard in another concentration camp, at Sobibor. He died in March 2012, waiting for his appeal to be heard, and the German Apellate court finally invalidated his conviction.

Hungary's role in World War II and Hungarians' complicity in the Holocaust still deeply divides Hungarian society.

The latest disagreement concerns the fate of the former railway station in the Jozsefvaros suburb, from which many Jews were deported.

The Holocaust Memorial Centre in Budapest had hoped to turn it into a permanent monument to the Jews. Instead, it looks set to be administered by historian Maria Schmidt and her House of Terror museum.

The conservative Ms Schmidt argues that the two periods of terror in recent Hungarian history - the Nazi and the Stalinist eras - should be presented side by side.

Hungarian liberals, including Laszlo Karsai, say the Holocaust was unique and that more should be done to help young Hungarians explore the often dismal role of their own countrymen in the "Final Solution".

- Published12 August 2013

- Published18 June 2013

- Published17 July 2012

- Published27 May 2011