Russian-majority areas watch Moscow's post-Crimea moves

- Published

Moscow originally said it was intervening in Crimea because of concern over the ill-treatment of Russians there - they make up more than half the population. So could the same happen in other parts of the former Soviet Union?

Eastern Ukraine

Ever since Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was ousted in February, there have been frequent pro-Russian demonstrations in Donetsk and other cities in eastern Ukraine. At least one person has been killed.

Russia has blamed far-right pro-Western demonstrators for escalating tensions there. Russian troops have staged military exercises near the border and remain in the area. It would not be difficult for them to move across into Ukraine itself.

If Russia is considering more territorial expansion, eastern Ukraine would be high on the list.

The political costs, however, could be high: Nato and Western leaders, external have warned against further expansionism. Crimea only became part of Ukraine in 1954. Ukraine's eastern border goes back much further.

Ukraine's military has now left Crimea altogether

However, once the separatist genie is out of the bottle, it is hard to put back in. There is even a mock campaign for Donetsk to become part of the UK - the city was founded by a Welsh industrialist, John Hughes, in the 19th Century.

Moldova

Attention has also focused on Trans-Dniester, a separatist region of Moldova that has already offered itself to Moscow. It proclaimed independence in 1990, but has never been recognised internationally. Trans-Dniester is majority Russian-speaking while most Moldovans speak Romanian.

Soldiers in the breakaway enclave of Trans-Dniester clean land at a military cemetery in the city of Tiraspol

There is also the southern pocket known as Gagauzia, an autonomous region of Moldova made up of four enclaves (population 160,000). The Gagauz are Turkic-speaking Orthodox Christians. In February 2014, Gagauzia held a referendum in which 98.4% of voters backed integration with a Russia-led customs union. The Moldovan government said the referendum was illegitimate.

Nato's commander in Europe warned Trans-Dniester could be Russia's next target. It already has 1,000 troops in the region, which borders Ukraine, near the city of Odessa.

Moldova is preparing to sign an association agreement with the EU, upping the diplomatic stakes if Russia did decide to annex Trans-Dniester.

Georgia

In 2008, Russia fought a brief war in Georgia that ended with the breakaway of two areas, South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

Although Moscow's stated aim was to protect Russian speakers, most residents are native speakers of Ossetian and Abkhaz respectively. However, many hold Russian passports and they are opposed to the Georgian government in Tbilisi.

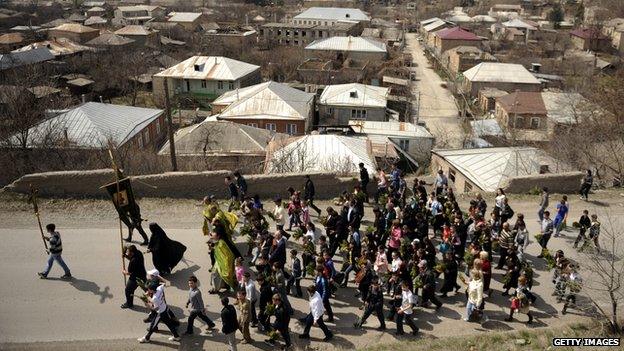

Palm Sunday in the South Ossetian capital, Tskhinvali - neither a part of Russia nor fully independent

Abkhazia had already declared independence unilaterally in 1999.

Since then, the two enclaves have existed in a kind of grey zone - not recognised internationally, but not formally part of Russia.

Abkhazia shares a border with Russia - not far from Sochi, the site of the 2014 Winter Olympics. Security was tightened for the Games.

South Ossetia borders the Russian Federation at North Ossetia. All goods must come in via a tunnel under the Caucasus mountain range. Prices are high. Unemployment and corruption are widespread.

Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia

Russians account for about a third of the population in both Latvia and Estonia. The Baltic republics regained independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

Both Latvia and Estonia require knowledge of their languages for citizenship. Some Russian speakers born in the countries are either unable or unwilling to become citizens as a result.

Some in Latvia are concerned about what might befall areas with large Russian-speaking populations

Many Russian speakers complain of discrimination, saying strict language laws make it hard to get jobs.

In Lithuania, ethnic Russians make up about 5% of the population and there is no requirement for them to pass a language test.

In mid-March, the Kremlin expressed "outrage" at the treatment of ethnic Russians in Estonia - the same reason it gave for intervening in Crimea.

However, the Baltic states are members of both the EU and Nato. Any Russian incursion would have serious consequences. Article 5 of the Nato treaty says that an attack on one member state is an attack on all.

Northern Kazakhstan

Russians account for more than half the population in northern Kazakhstan which, like Crimea, was once a part of Russia itself.

Ties between the two go back to tsarist times, when northern cities such as Pavlodar and Uralsk were founded by the Russians as military outposts.

An actor dressed as the poet Pushkin greets the Russian and Kazakh presidents on a visit to Uralsk

Like Ukraine, Kazakhstan signed an agreement on nuclear disarmament in 1994 in exchange for protection. It has no port like Sevastopol in Crimea, but it does have the Baikonur space facility.

However, Kazakhstan already has close ties with Russia - it is one of two other members (along with Belarus) of Moscow's customs union.

Kazakhstan is remaining officially neutral in the matter of Ukraine, but has called for a peaceful resolution.

The other Central Asian republics

The percentage of ethnic Russians in central Asia ranges from 1.1% in Tajikistan to 12.5% in Kyrgyzstan. After independence in 1991, large numbers of Russians emigrated.

However, the Central Asian economies remain tied to Russia - both in terms of trade and remittances from migrants working there.

It seems unlikely that Moscow would seek to intervene in the region.

However, the post-Crimea turmoil could still have an effect, as the rouble falls and sanctions hit Russian businesses. Jobless migrants returning from Russia could cause trouble for the governments in Dushanbe or Bishkek.

Millions of Tajiks work in Russia as labourers, sending money home but often spending years away

Armenia and Azerbaijan

Armenia has no Russian population to speak of, and Azerbaijan has just 1%. Both countries tread a geopolitical tightrope between Russia and the West.

Like Ukraine, Armenia had been preparing to sign an association agreement with the EU. But in September, it announced it would be joining the Russian-led customs union instead.

Since Armenian independence in 1991, Russia has retained a military base at Gyumri.

Last September, Armenia's President Serzh Sarkisian (right, pink tie) jettisoned closer ties with the EU in favour of the customs union led by Russia and President Vladimir Putin (left)

Azerbaijan exports oil and natural gas to the EU and is less economically dependent. A pipeline that ends in Turkey allows it to skirt Russian territory.

Russia would like to keep both countries in its sphere of influence, but it is likely to use economic, rather than military, measures.

Belarus

Belarus is already closely aligned with Moscow. Although about 8.3% of the population identify as Russian, more than 70% speak the language.

There is no reason why Russia would seek to intervene: the two governments could not be any closer. Belarus is in an economic union with Russia, and Russian is an official language.

Despite the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, Belarus and other former countries of the USSR continue to mark Defence of the Fatherland Day on 23 February each year

- Published23 April 2014

- Published7 March 2014

- Published18 March 2014