Ukraine crisis: Latvia's Russian speakers find their voice

- Published

Russian speakers in Latvia mark the anniversary of the end of World War Two with a rally on 9 May

As Ukraine is torn apart by divisions between nationalists and pro-Moscow separatists, other former Soviet States with large Russian-speaking populations are wondering nervously if the same thing could happen to them.

Particularly in Latvia, where Russian-speakers make up 40% of the population.

But Latvian Russian speakers who are pro-European are starting to make their voices heard.

Their first language is Russian. They consume media from Moscow. They may even support Russian President Vladimir Putin's annexation of Crimea. But many of Latvia's Russian-speakers are clear about one thing: they do not want to join Russia.

"There are Latvian Russians who do not support Mr Putin and who feel like Europeans," said Igor Vatolin, a Russian-speaking Latvian, when we met in a cafe.

"Of course there are Russian issues, but those issues should be discussed and solved in dialogue with the Latvian authorities inside the country."

Separate lives

Mr Vatolin has set up an organisation called the Movement of European Russians to show that the small number of very vocal supporters of Mr Putin in Latvia do not represent the views of most Russian speakers here.

Among the flags waved by pro-Russians in Riga was the tricolour of the Donetsk separatists in east Ukraine

In the streets of the elegant capital Riga, where half of the population is Russian-speaking, you hear as much Russian being spoken as Latvian.

Although the two communities often live very separate lives, speaking predominantly one language or the other, it is rare to see signs of tension between the two groups. But deep-seated resentments do exist.

Latvia has the largest Russian-speaking population in the EU and many are descended from people who moved here during the Soviet era.

Often Russians came here from elsewhere in the Soviet Union simply looking for a better life, in the same way Europeans today move around the EU.

But the mass migration, say Latvian historians, was also an attempt by Stalin to dilute and eventually destroy Latvia's language and culture.

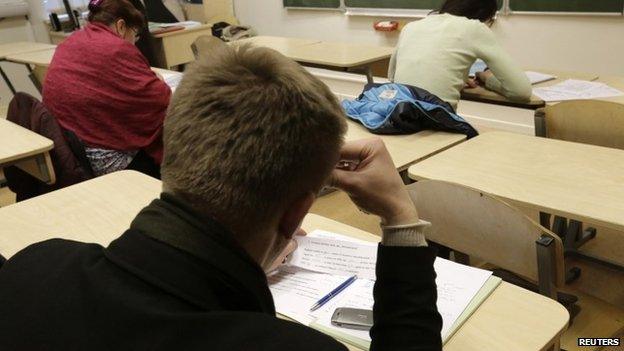

Russian speakers in Latvia have to pass a Latvian language and culture citizenship test

Half the population of Latvia's elegant capital Riga is Russian-speaking

Latvians have painful memories of this Soviet oppression. Every family can tell you a story of a grandparent or relative who was killed by Stalin's troops, or suddenly deported to Siberia without reason or warning.

Russian speakers on the other hand say they have suffered discrimination since Latvian independence in 1991.

Particularly galling for many, such as those who came here during the Soviet occupation, is that they were not automatically given Latvian citizenship after the collapse of the USSR - even though many supported Latvian independence.

Instead they have to take a Latvian language and culture citizenship test. As a result, 300,000 Russian speakers - 15% of Latvia's population - are still classed as so-called non-citizens, and so do not have a vote.

It is a complicated issue, which is easily politicised. And one that Mr Putin is vocal about.

Crimea-style referendum

Some older people never managed to learn Latvian, and so are unable to pass the test and as a result have found themselves disenfranchised.

Although the two communities often live very separate lives it is rare to see signs of tension

Others, however, refuse to take the test as a political statement. Or even prefer to keep their non-citizen passport because it enables them to travel visa-free to Russia on business or to see family.

But most Russian-speakers have Latvian citizenship. And according to the Russian-speaking mayor of Riga, Nils Usakovs, they are well-integrated and take advantage of the ability to work and travel elsewhere in the European Union - and so they tend to have more links with the rest of the EU than with Russia.

"If you take for instance a Russian-speaking teenager, most likely he has already been a couple of times to Berlin, or the UK, or at least Stockholm. He has probably never been to Russia because you need a visa to get to Russia, and because Moscow is more expensive than London sometimes."

According to Professor Juris Rozenvalds, a sociologist at the University of Latvia, most Russian speakers in Latvia would oppose joining Russia in a Crimea-style referendum, because they see better economic prospects within the European Union.

"European Russians are more educated, and they use the internet," he said.

"And they see what the tendencies are at the moment in Russia. They see that the economic situation in Russia is comparatively hard. Because you have relatively high prices for oil and gas, and virtually zero growth in the economy."

The Russian-speaking mayor of Riga, Nils Usakovs, says the community is well-integrated

Back in the cafe, Mr Vatolin tells me that better rights for Russian speakers in the Baltics was once seen as a human rights issue. Today he believes it is now a matter of national security.

The main aim of his Movement of European Russians is to push Latvia's government to improve minority rights here, before Mr Putin attempts to, by offering his "protection".

"So we say to Mr Putin: We are not tools of your influence here in Latvia, but we say to our [Latvian] government: Please do solve those Russian issues, which Mr Putin regards as tools of his influence, otherwise it can be the same thing as in the Crimea and it's rather serious."

If Mr Putin decides he wants to create instability in the Baltic republics, he could use the non-citizenship issue, Mr Vatolin believes.

If the Kremlin suddenly decided, for example, to give Russian passports to the 300,000 Russian-speaking non-citizens here, Latvia would have a problem.

Now it seems the country has two choices.

Either each side becomes more nationalistic, and Latvia risks heading in the direction of Ukraine. Or the crisis in Ukraine becomes an incentive for both sides to work on finally solving the divisions within Latvian society.

- Published9 June 2014

- Published6 June 2014

- Published30 November 2022

- Published10 April 2014

- Published26 April 2014

- Published26 March 2014