Russia economy: What is the risk of meltdown?

- Published

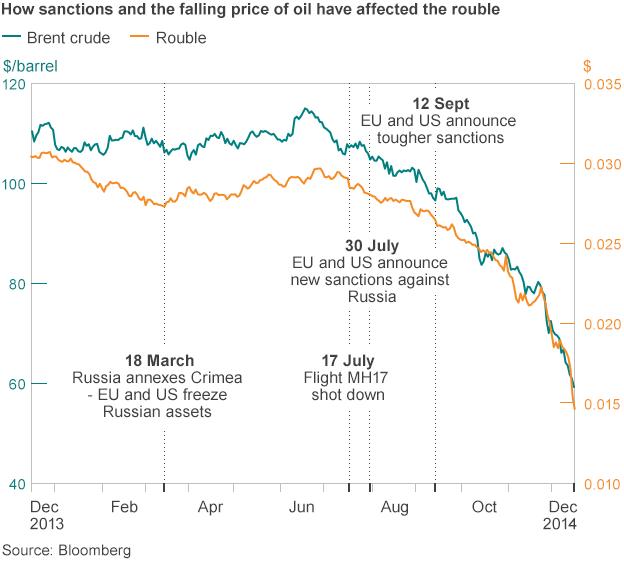

Russians have seen their currency's value tumble by half since the start of the year

Russia's Central Bank has raised interest rates to 17%, but the rouble has continued to plummet, prompting fears of economic crisis.

Russians are reminded of the dark days of 1998, when President Boris Yeltsin's government defaulted on its debt. But how severe are the problems and is there a way out?

What has gone wrong?

Russia relies on oil and gas for half its tax revenue and needs the price of a barrel to be at $100 to balance its books. Instead, the price is closer to $60. The value of the rouble has plummeted pretty much in tandem, leading to a sense of panic in the markets.

Even before Russia's annexation of Crimea from Ukraine, Russia's economy was in trouble. But then came Western sanctions - and Russia's counter sanctions - which have made things worse.

Some believe a direct cause of this latest crisis was a mysterious bond deal involving Russia's biggest oil company, Rosneft.

Rosneft raised almost $10bn in rouble bonds late last week and the central bank then said it was happy to use it as collateral.

The markets were spooked as it looked as though the bank was giving direct support to a state-run company - and one run by a close ally of President Putin, Igor Sechin, at that.

Whatever the cause, there is a loss of confidence in the central bank's ability to respond to the crisis.

What are Russia's main economic problems?

The rouble has lost half its value this year, and it is feeding through to prices

Inflation is now at around 9%, caused by the weaker rouble, higher food prices and Western sanctions

Russia's economy has been slowing down since 2012 and was already on the verge of recession

Now, with oil at $60 a barrel, the Central Bank is warning of severe recession

Capital flows out of Russia could reach $128bn this year, the Central Bank estimates

Some leading banks, hit by sanctions, are unable to raise mid- to long-term financing outside Russia

Banks and companies have significant foreign debt - at least $200bn

Around $100bn of that debt will have to be repaid in 2015 and Russia's export receipts have declined by $140bn

Is it all bad?

Frankly, no. Russia's looking at a healthy $200bn trade surplus for 2014. So a healthy balance sheet on the surface means little problem with raising external capital.

Russia also has more than $400bn in foreign reserves.

And until recently the diving rouble almost cancelled out the plummeting oil price, for Russia's finances, at least.

Many Russian manufacturers have also benefited from a bigger domestic market because of the Kremlin's own sanctions on Western imports.

So why the panic?

Many Russian commentators see a perfect storm and fear a return to financial meltdown of 1998, when the rouble fell through the floor and prompted Russia to default on its debt. Interest rates soared to 100%, the currency was devalued, an IMF bailout failed and capital controls were brought in.

Russians were traumatised when they were unable to get hold of their money in August 1998

"I remember 1998 very well and we have really come back to those times," Senior Credit Analyst Egor Fedorov of ING Bank in Moscow told BBC News.

These days, Russia's reserves and finances are in a far better state, but with the rouble in freefall and a Central Bank apparently failing to respond, the problem is sentiment.

Paris-based economist Sergei Guriev speaks of uncharted waters. "The markets no longer trust the Central Bank. Every hour the situation is changing," he says.

Former Central Bank deputy chairman Sergey Aleksashenko believes today's situation is much more serious than 1998 as it is far more complex.

"It was enormously painful, but the mistakes were evident and the government knew what it had to do," he says.

What are ordinary Russians feeling?

The rouble pays for less than it did, salaries are not keeping pace with inflation of around 9% and pensions are worth far less in real terms.

"The main shock for Russians will be the lower purchasing power of their wages and their pensions," says Sergei Guriev.

What effect are Russia's economic woes having on everyday life?

But so far Russia's state TV channels are saying little about the crisis and, as only one in three families has savings, it will take a few months for the reality to take effect, Mr Aleksashenko says.

Job losses are yet to feed through, but state-run gas giant Gazprom is said to be planning to axe between 15% and 25% of its 459,000-strong workforce.

And then there is the mortgage market. Russia has seen a major expansion in its property loan market this year. Although interest rates have been going through the roof, Russians have tried to plough their savings into the relatively safe haven of bricks and mortar.

This latest interest rate rise, to 17%, could put a stop to that.

A relatively small proportion, around 3%, are foreign currency mortgages in dollars and euros and they have been hit hardest.

Who is to blame for the panic?

Central Bank head Elvira Nabiullina is being singled out for criticism. To some, the late-night decision on interest rates smacked of desperation. And while the rouble rebounded for a few hours, its freefall continued later.

Elvira Nabiullina was appointed head of the central bank by President Putin in 2013

The bank has appeared powerless in the face of a crumbling currency. Last month, it fully floated the rouble in an attempt to stop investors betting against the currency.

For ING's Egor Fedorov, that action failed, creating "an explosion" in the Russian economy. On the back of the continuing oil slump, he says the bank undermined trust in its ability to support the currency.

The mysterious Rosneft bond deal, which appears to have triggered a loss of confidence, may have also undermined the bank's independence because it stayed silent.

Is President Putin safe?

Vladimir Putin has regularly made a point of the Central Bank's independence from political leaders but his government's policies are partly responsible for the state Russians find their economy in.

Earlier this month, President Putin promised an amnesty to Russians who brought capital back from abroad

Russians looked to Mr Putin to pull them out of the mess that his mentor Boris Yeltsin had put them in and it largely worked.

His popularity ratings are still high but he has no control over two of the key elements of the current crisis, the oil price and the severe recession that Russia is facing.

The only way he could directly influence the current crisis would be by finding a way to halt Western sanctions, Sergei Aleksashenko argues.

But that would require a shift of policy in Ukraine, and few believe that will happen.

What's left in Russia's armoury?

It depends whether the rouble and oil values carry on falling.

Interest rates could continue to rise.

But a more drastic next step would be capital controls, in other words restricting the flow of money out of Russia. That would send worrying signals to foreign investors and President Putin is known to be opposed to such a move.

He removed capital controls in 2006.

- Published16 December 2014

- Published15 December 2014