The 2015 Greek euro drama

- Published

- comments

On 3 January the Syriza leader addressed a party congress where election candidates were chosen

It did not take long. The game is very much in play. Greek voters are being bombarded with warnings about what is at stake when they go to the polls on 25 January.

There is little that is coded in these messages. When a country has been bailed out to the tune of €240bn (£187bn; $286bn) there is no such thing as non-interference in Greece's internal politics.

Most of the European political establishment does not want Greece to elect the radical left party Syriza led by Alexis Tsipras. The party is currently narrowly ahead in the polls. Mr Tsipras is looking for debt relief and hinting that his election could spark wider change in Europe. He frames his message as "ending austerity politics".

The Germans and others fear that under Mr Tsipras, Greece would not fully comply with the conditions of the bailout agreements negotiated with the European Central Bank, the EU and IMF.

So German politicians are sending out their new year messages. Unlike in 2012, a Greek exit from the euro would now be considered "manageable". The eurozone has built up much greater protection against shocks. The German Vice Chancellor, Sigmar Gabriel, said "that's why we cannot be blackmailed". He wants Greece to stay in the eurozone, he said, but it had to abide by the agreements it had made.

One German magazine quotes an official saying that a Greek departure would be almost "inevitable" if Syriza wins. That is the threat aimed directly at the voters: vote the wrong way and you could find yourselves outside the eurozone.

The French President, Francois Hollande, today tried to define the vote as about whether to stay in the euro. "Countries like Spain and Greece," he said, had "paid a heavy price to stay in the euro" and it was "up to the Greeks to decide whether to remain part of the single currency".

An Athens soup kitchen - the crisis has thrown many people into poverty

Weighing up risks

The Greek government will say that a vote for Syriza risks endangering all the hard-earned progress that has been made. In 2014 Greece managed to achieve a budget surplus, with growth returning to the economy.

So over the next three weeks we will witness a high-stakes political game. The European establishment knows only too well that despite the depth of the crisis - the Greek economy has shrunk 25% in the past five years - the polls indicate that around 60% of Greek voters want to stay in the euro.

But Alexis Tsipras knows several things too. Chancellor Angela Merkel has always shifted her position when she felt the eurozone under threat. (She was once against setting up the bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism.) Would she be sanguine about Greece leaving, when so much of her legacy is tied up with her efforts to save the single currency?

Also Mr Tsipras has allies. Spain now has in Podemos a radical left party which shares many of Syriza's views. It is currently at 22% in the polls. Would the French and Italians really be prepared to see Greece leave, or would a split develop with Germany? Again today (Monday) Francois Hollande has said "Europe cannot continue to be identified by austerity".

Also, can German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble be certain there would be no eurozone contagion? Certainly at the moment the borrowing costs of countries like Italy are at record lows, but the prospect of a Greek departure could still unnerve the eurozone and the markets.

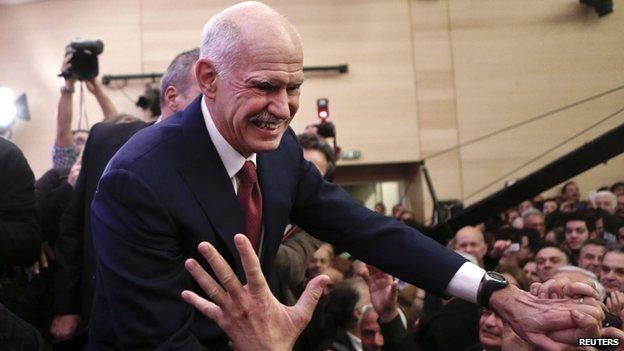

Ex-PM George Papandreou has a new party - the Movement of Democratic Socialists

Disaster warnings

Alexis Tsipras will of course say that he is not intending to leave the single currency, but to negotiate a better deal which would allow Greece to grow again and to reduce high unemployment. His political opponents, however, are already framing the debate differently.

It should be recalled how in 2012 there were dramatic warnings against voting for the radical left. The Greeks were told they would face "mass poverty".

The man who negotiated with private investors to accept losses on their Greek holdings said the consequences of leaving the single currency were "somewhere between catastrophic and Armageddon". The Greek prime minister warned that if there was no stable government the country would run out of money in weeks. Such dramatic scenarios may once again tip the scales against Syriza and in favour of the current government.

If Mr Tsipras wins, and if he can build a coalition, then I expect tense negotiations to follow. Germany will work to avoid Greece leaving the eurozone, but it would not be able to sell to German voters any backing away from reforms or any weakening of the bailout conditions. Mr Tsipras knows that a failed negotiation and an exit from the euro would lead to short-term economic upheaval, and that will make him cautious.

So later this month there could be days fraught with risk - particularly risk of a miscalculation.

- Published30 December 2014

- Published28 June 2023

- Published29 December 2014