Furore over novel depicting Muslim-run France

- Published

Houellebecq argues that the idea of a Muslim party changing the face of French politics is perfectly plausible

The BBC's Hugh Schofield in Paris reports on the publication of a provocative new book which depicts France as an Islamicised country where universities are compelled to teach the Koran, women are made to wear the veil and polygamy is lawful.

In the year 2022, France has continued its slow collapse and a Muslim party leader takes over as the country's new president.

Women are encouraged to leave their jobs and unemployment falls. Crime evaporates in the banlieues. Veils become the norm and polygamy is authorised.

Universities are made to teach the Koran.

Anti-Islamic scare-mongering?

Torpid and decadent, the population reverts to its collaborationist instincts. It accepts the new Islamist France.

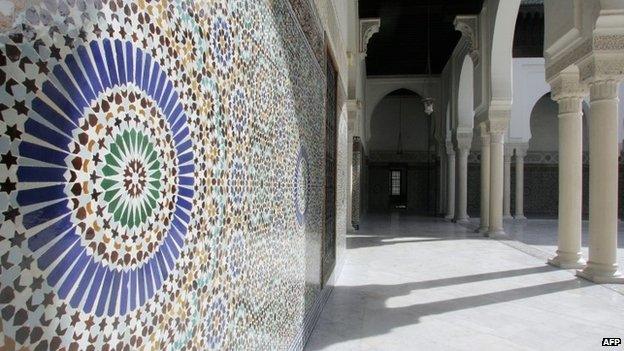

Parts of France have a rich Islamic culture, with the Paris Mosque widely admired for the beauty of its architecture and its minaret which is 33m high

Houellebecq says French Muslims are conservative by background and do not feel at home with the left - especially since the introduction of gay marriage - but are equally alienated by the political right

Such is the characteristically provocative plot of the new novel by France's most famous living author Michel Houellebecq.

Soumission (Submission) goes on sale on Wednesday, but for a week now the arguments have been raging.

Is the book anti-Islamic scare-mongering in the guise of literature? Does the excuse that it is fiction have any validity if the book gives succour to the far-right?

Or on the contrary, is Houellebecq simply doing the job of an artist: holding a mirror to the world, exaggerating perhaps but honestly telling the deeper truths?

The row is all the more intense because Islam and identity are already at the heart of a fierce national debate in France.

Runaway success

Last year the anti-immigration National Front made an extraordinary leap forward by winning a national election - for the European Parliament - for the first time.

Outbreaks of Islamophobia sometimes happen in France - these Muslim war graves were desecrated by vandals in 2008

Soumission (Submission) goes on sale on Wednesday, but for a week now the arguments have been raging

Its leader Marine Le Pen is a serious contender for the 2017 presidential election. Indeed in Soumission, it is in order to keep Le Pen out that the mainstream parties rally behind the charismatic Mohammed Ben Abbes.

Background to the new novel is also shaped by the runaway success of the book Le Suicide Francais (French suicide), by right-wing journalist Eric Zemmour, one of whose themes is also France's moral collapse in the face of newly-confident Islam.

Critics of Houellebecq say his novel lends intellectual credibility to the theses of Mr Zemmour and other "neo-reactionaries".

For Laurent Joffrin of the left-wing newspaper Liberation, Houellebecq is "warming Marine Le Pen's seat at the Cafe Flore" - legendary haunt of the left-bank philosophers on the river Seine.

"Whether or not it is the intention, the novel has a clear political resonance," wrote Mr Joffrin.

"Once the media furore has died down, the book will go down as a key moment in the history of ideas - when the theses of the far right made their entry - or re-entry - into great literature."

Others have gone further. Television presenter Ali Baddou said that "this book makes me sick... I felt insulted. The year kicks off with Islamophobia disseminated in the work of a great French novelist."

From the other side, supporters say Houellebecq is addressing issues which the metropolitan and left-leaning elite pretend do not exist.

'Stupidest of religions'

Philosopher and member of the Academie Francaise Alain Finkielkraut described Houellebecq as "our great novelist of what might come to be".

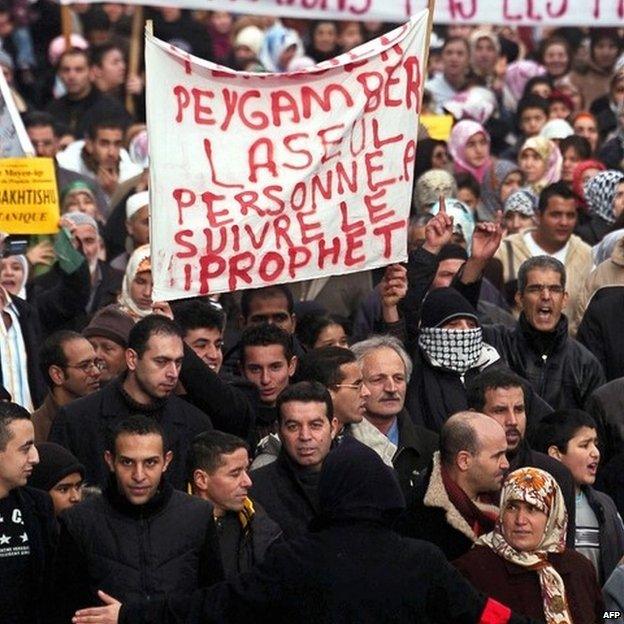

In France the right of Muslims to wear the niqab in public has generated fierce debate

The premise of the novel is that the the mainstream parties of France rally behind the charismatic Mohammed Ben Abbes in order to keep Marine Le Pen out of power

"By raising the eventual Islamisation of France, he is touching where it hurts - and the progressives are all crying Ow!"

Houellebecq, who once described Islam as the "stupidest of religions", has denied any desire to be provocative.

In interviews ahead of publication, he said the idea of a Muslim party changing the face of French politics was perfectly plausible - though he agreed he had accelerated the timeframe.

"I tried to put myself in the place of a Muslim, and I realised that, in reality, they are in a totally schizophrenic situation," Houellebecq told the Paris Review.

Muslims, he said, were conservative by background and did not feel at home with the left, especially since the socialists introduced gay marriage. But equally they felt alienated by a political right that rejected them.

Enlightenment demise

"So if a Muslim wants to vote, what's he supposed to do? The truth is, he's in an impossible situation. He has no representation whatsoever," he said.

The book paints a picture of the Koran being compulsory at French universities

Houellebecq said the wider theme of his book is the return of religion to the centre of human existence, and the demise of the Enlightenment ideas that have prevailed since the 18th Century.

"The return of religion is a worldwide movement, a tidal wave… Atheism is too sad… I think right now we are living through the end of a historic movement which began centuries ago, at the end of the Middle Ages," he told Le Figaro.

In the end Houellebecq implies in his interviews that the return of religion is a good thing - he says he himself is no longer atheist - and that even Islam is better than the existential emptiness of Enlightenment Man.

"In the end the Koran turns out to be much better than I thought, now that I've re-read it - or rather, read it," he told Paris Review.

"Obviously, as with all religious texts, there is room for interpretation, but an honest reading will conclude that a holy war of aggression is not generally sanctioned, prayer alone is valid. So you might say I've changed my opinion.

"That's why I don't feel that I'm writing out of fear. I feel, rather, that we can make arrangements. The feminists will not be able to, if we're being completely honest. But I and lots of other people will."

At the end of the book Houellebecq's hero Francois has himself "made arrangements" - going back to his teaching job at the Islamicised Sorbonne, tempted by a pay increase and the promise of several wives.

- Published11 November 2010

- Published8 November 2010

- Published19 November 2014

- Published1 July 2014

- Published31 May 2018

- Published19 November 2014