Humanist campaign challenges blasphemy laws

- Published

Supporters of blasphemy laws say they protect religious feelings

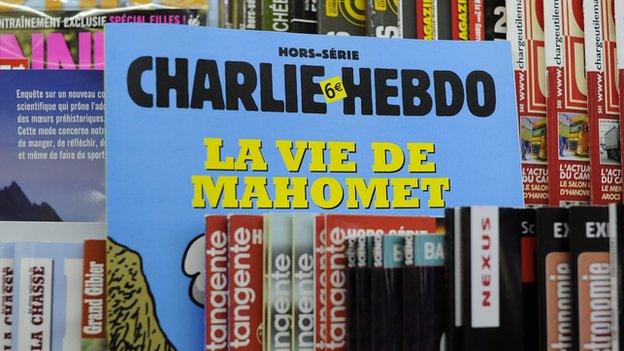

Blasphemy laws are being challenged in a new global campaign launched by a coalition of humanist organisations. The International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) says that, in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in France, the time is right for countries to abolish laws that protect religious sensibilities. But blasphemy laws nevertheless remain popular in many parts of the world.

The attacks on the staff of the Charlie Hebdo satirical magazine led to a massive response in defence of free speech - in France, but also across the world.

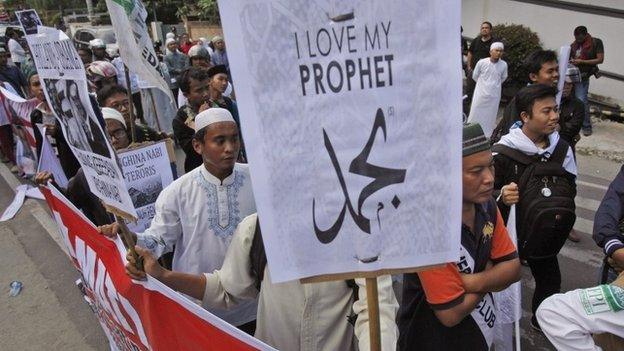

Equally intensely, some parts of the world saw protests against both the original cartoons, and the subsequent publication of another image of the Prophet Muhammad.

There is a particular prohibition against showing the image of Muhammad in some strands of Islam, but the crime of blasphemy can be found in many religions and countries.

To its supporters, it's a crucial way of protecting religious feelings and minorities; for others, it impedes free speech and can be used to suppress political dissent.

Minority persecution

Sonja Eggerickx is the president of IHEU which works to promote an evidence-led ethical society.

She says the campaign is intended to support local people on the ground already working against blasphemy laws.

"The idea that 'insult' to religion is a crime is why humanists like Asif Mohiuddin are jailed in Bangladesh, is why secularists like Raif Badawi are being lashed in Saudi Arabia, is why atheists and religious minorities are persecuted in places like Afghanistan, Egypt, Pakistan, Iran, Sudan, and the list goes on," she says.

Raif Badawi was sentenced to 1,000 lashes in May 2014 by a Saudi court after being found guilty of insulting Islamic religious figures on his blog.

Philip Blackwood was charged in Burma in relation to a picture showing Buddha wearing headphones

Pakistan also has severe laws protecting religious feelings.

Asia Bibi, a 50-year-old mother-of-five, has been on death row since 2010 after being convicted of insulting Islam during an argument over a glass of water.

John Pontifex from the charity Aid to the Church in Need, which campaigns for Christian minorities, says many cases never reach court.

"They [blasphemy laws] give the fig leaf of respectability to acts of violence against Christians and others accused of crimes they very often have not committed," he said.

But do blasphemy laws help society in any way?

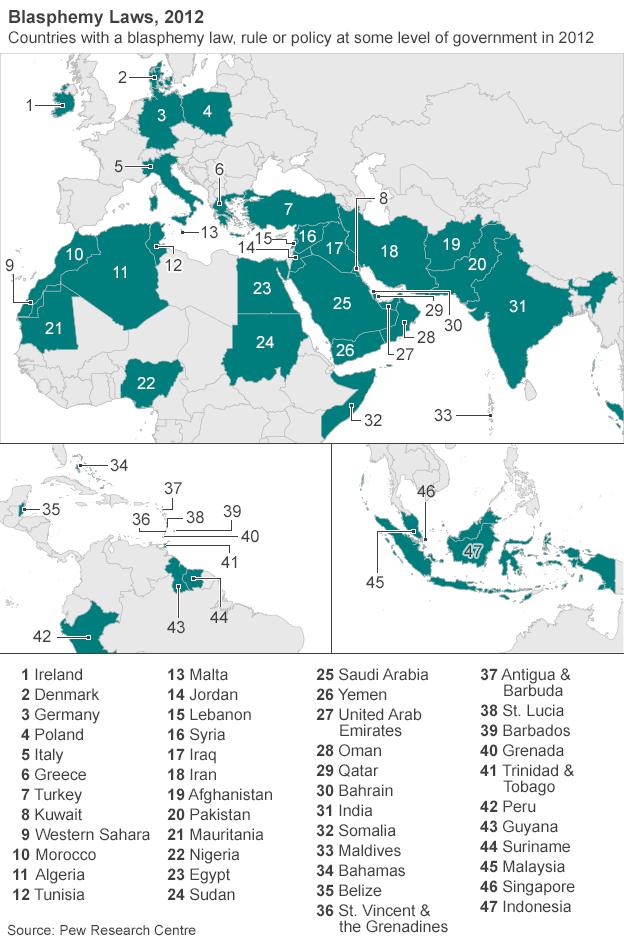

The Pew Research Centre has found that the laws are most common in the Middle East and North Africa.

And it is from this region that the most vocal advocates of the laws can be found.

The Organisation of Islamic Co-operation, which represents 56 Islamic states, has repeatedly tried to get United Nations support for an international measure to outlaw insults to religion.

It says that such a resolution would protect groups from discrimination.

Last year, the organisation's secretary general, Iyan Ameen Madani, said that freedom of expression was clashing with Islamic teachings.

He criticised countries who refused to limit free speech, which he said was harming religious minorities.

"Muslim countries enacting laws to ensure respect for the sanctity and reputation of religious values, scriptures and personalities for promotion of peace in society, are criticised on account of limiting this freedom through blasphemy laws," he said.

Those laws are not just found in the Middle East.

Blasphemy in Europe

In Denmark, paragraph 140 of the penal code is about blasphemy. The paragraph has not been used since 1938 when a Nazi group was convicted for anti-Semitic propaganda.

In Myanmar, also known as Burma, in December, three men were charged by the authorities with insulting religion after they allegedly distributed a picture depicting Buddha wearing headphones.

Some European countries also criminalise anti-religious sentiments in some form.

In 2012 there were 99 convictions for "public blasphemy" in Malta, with punishments ranging from fines to imprisonment.

And in 2014, Russian MPs voted for a new law against offending religious feelings.

It followed a political protest by members of the group Pussy Riot in Moscow's Orthodox cathedral.

Pussy Riot were charged with blasphemy for performing a protest song in Moscow's main cathedral

The charge against the three included "insult to religious feelings".

In Ireland, campaigners are furious that the government there has reneged on a promise to hold a referendum on its blasphemy laws, which were themselves only introduced in 2009.

And last year, a Greek man who satirised a dead Orthodox monk on Facebook was sentenced to 10 months in prison.

Those who want to extend religious insult laws are also making plans.

The UN Human Rights Council says it is likely that the issue of insulting religions will be raised at the council's upcoming sessions in March, at the request of Saudi Arabia.

'Minority voices'

The IHEU campaign, though, is not about encouraging discrimination, says Bob Churchill, its director of communications.

"Our campaign does not target laws against incitement to hatred, which are legitimate," he said.

Mr Churchill also rejects the charge of cultural imperialism.

"The reality is that minority voices for change and reform are there. The problem is they often cannot be heard."

- Published23 January 2015

- Published20 January 2015

- Published15 January 2015

- Published8 January 2015