Croats and Serbs still bitter after genocide verdict

- Published

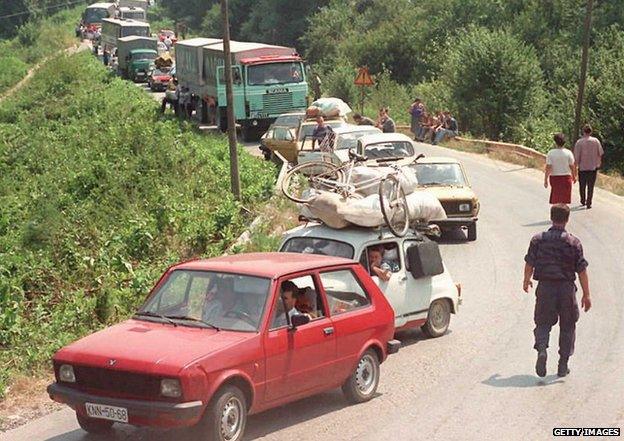

Thousands of Croatian Serbs fled the Krajina region in August 1995

The atrocities of the 1991-1995 war between Croatia and Serbia are still vivid for citizens of both countries and the rejection of two rival claims for genocide by the International Court of Justice will not lessen the pain.

Croatia sued over the capture of the town of Vukovar, where 260 men were murdered in a notorious massacre and the rest sent to Serb detention camps. For Croatia's Serb population, the capture of Krajina was equally traumatic, when 200,000 civilians were forced to flee the onslaught of Croatia's Operation Storm.

These are the reactions to the ICJ's verdicts from people involved in both stories.

Bojan Popovic, born in Krajina, now in Displaced Persons Association, Belgrade

This a political verdict and it is a very upsetting day for us. A lot of people lost their lives, many lost their homes. It's not just five or 10, it's hundreds of thousands of people.

Although nobody from my family was murdered, my father's village home was burned and our flat near Zagreb was taken. They took all we had.

The city of Knin came under bombardment as Croatian forces advanced in Krajina

I was seven years old and as I was young I didn't understand what happened. But then my parents didn't understand what happened either.

It all began when we found out that the main road out of our village had been blocked off. There was shooting and grenade explosions everywhere. Men, women and children fled from one village to the next.

The Croats had prepared everything and had help from other countries. Many think the Serbs did all the killing, but in fact we lost a lot of people.

My family is in Belgrade and a lot of people came here because they have relatives, but refugees moved across Serbia and Kosovo, and after the conflict there they scattered around the world.

There are between 25,000 and 30,000 people in our association.

While we live for tomorrow, we remember the past.

Branimir Bradaric, Vukovar journalist for Vecernji List, Croatia

When it comes to the war, Vukovar is still a divided town, and so it remains with this verdict.

People pay their respects to the victims of the Vukovar massacre, at a memorial at Ovcara farm

Vukovar today has about 22,000 inhabitants, half the size of its pre-war population. One-third here are Serbs, the rest are Croats.

There are those who are disappointed that the Croatian claim has been rejected, and those who think the Serbian claim should have been accepted.

People are still bitter here, whether they lost a family member, were wounded or survived the Serbian detention camps. And every Croatian family in Vukovar suffered.

Croats here see the war crimes tribunal in The Hague and the ICJ as political, and believe the government should seek redress in another court. If not, they want the government to address the hundreds of people still missing from the war, when Serbia negotiates to join the European Union.

Nevertheless, the majority of Vukovar's population was realistic about the case, so today's ICJ decision was not a surprise.

A major problem for both communities now is that people, especially the young, are abandoning Vukovar in search of work.

Dejan Jovic, former presidential adviser, now professor at University of Zagreb

This is a sober verdict and it could bring some more balance, if there is goodwill politically to end the endless discussion of the wars of the 1990s.

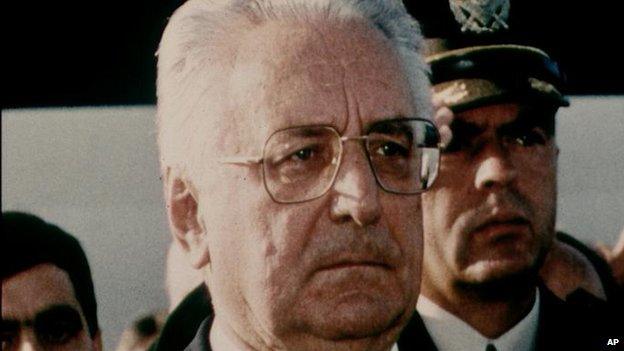

Croatia's President Franjo Tudjman launched the genocide case against Serbia in 1999

The wars have been heavily manipulated, and in Croatia in particular there is a myth based on the idea that Croatia was a victim and a winner in this war. The TV news is still full every day of news about the war, to the extent that it is being celebrated, not commemorated.

This is very fertile ground for nationalism and does not focus on the victims or the crimes, but is used to mobilise nationalist sentiments with a view to treating the other side as guilty.

Croatia brought its case in 1999, when President Franjo Tudjman's HDZ party was weak and turned to nationalism.

With this verdict from the ICJ, very few here will change their minds: if you have 20 years of propaganda you are closed to the other side's view.

It could be a positive development - provided we don't take it as the end of the story.

But there is still a feeling that there is a taboo and a national myth.

- Published3 February 2015

- Published3 February 2015

- Published29 April 2013