Gallipoli centenary: World perspectives on a brutal battle

- Published

Turkey tourist guide at Gallipoli

People from around the world are marking the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Gallipoli - one of the costliest phases of World War One.

It is thought that more than 130,000 died as the Allies unsuccessfully battled the Ottoman army for control of the Dardanelles strait.

Here, BBC correspondents compare how the battle is remembered in some of the countries affected, and what it means for their citizens today.

Australia and New Zealand: Phil Mercer, BBC News, Melbourne

More than 8,700 Australians died at Gallipoli, alongside almost 2,800 New Zealanders

Identity lies at the heart of the Australian psyche. Who are we and what do we stand for?

Australia's modern history revolves around colonisation by the British in 1788 and independence in 1901, but some look elsewhere for a clearer definition of nationhood.

To them the heroism of the Anzacs at Gallipoli was an awakening for a fledging nation. The slaughter in north-western Turkey might not have altered the course of the Great War, but it changed the way a nation saw itself and its place in the world.

Crucially, the tragedy bore an enduring sense of self-belief. The troops' pride, "mateship" and ingenuity are widely considered to be the cornerstones of Australian culture.

More than 8,700 Australians died at Gallipoli, alongside almost 2,800 New Zealanders. As small countries, they suffered disproportionately high rates of casualties compared to others.

New Zealand had also fought unerringly in the name of the British Empire but it, too, emerged from the darkness of WW1 empowered by a greater sense of confidence.

Not everyone considers the Anzacs to be founding fathers, but many millions of antipodeans do. To them, the legend is sacred.

Petty Officer Danny Allen, the New Zealand sub-branch president at the Caulfield Returned and Services Club in Melbourne, told me that he hoped the legacy of the Anzacs would always endure.

"Thanks to those that gave the ultimate, we have a life of freedom today, and I would like to think that memory is kept on for evermore," he said.

Britain: Robert Hall, BBC Special Correspondent

The Lancashire Fusiliers stormed ashore at Cape Helles on the Gallipoli peninsula on 25 April 1915

British troops fighting alongside Indian and Irish contingents lost 25,000 people in a military adventure championed by one Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty.

And yet, across the UK as a whole, Gallipoli has never had the resonance shared in Australia and New Zealand.

In Australia and New Zealand, Gallipoli is portrayed as the sacrifice of young men, who had volunteered to serve, by poor British commanders.

For the British, Gallipoli was a sideshow, a grand plan poorly executed and overshadowed by the bloodshed at Ypres and on the Somme.

Prince Charles is visiting the British landing beaches in Gallipoli again as part of the centenary events

The ceremonies on the Gallipoli peninsula this week mirror contrasting attitudes; at Anzac Cove an estimated 10,000 pilgrims will gather on the hilly scrubland where the Turks held out so tenaciously.

The service at one of the beaches where the British landed, also attended by Prince Charles and Prince Harry, will include a group of family members, but is a smaller, more formal affair.

A century ago, the Turkish commander famously told his men: " I do not order you to attack, I order you to die."

Whatever their viewpoint, every nation that fought here is trying to understand the carnage which followed those words.

Turkey: Selin Girit, BBC News, Gallipoli

Gallipoli Martyrs' Memorial was built in 1960 to commemorate the soldiers who fought and died

The historical peninsula of Gallipoli has drawn millions of foreign tourists since the battle - mostly from Australia and New Zealand. But recently local tourists have started to show an increasing interest too.

Tourist guide Yusuf Kirca says numerous tours are being organised by schools and municipalities, from all around Turkey.

In the last decade there has been a ten-fold increase in the number of tourists visiting Gallipoli.

As this year marks the centenary of the battle, the number of tourists is set to hit record levels.

Gallipoli was the only big battle the Ottoman Empire won throughout WW1.

Historian Ayhan Aktar says Gallipoli's location - at the mouth of the Dardanelles straits leading to Istanbul - meant defending it was extremely important.

The victory "gave great morale to the Ottoman officers", he adds.

More Turkish tourists are visiting the memorial

One of the officers who fought in Gallipoli was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk - the founder of modern Turkey.

Because of his involvement, the Battle of Gallipoli is often seen as a preparatory stage of Turkey's war of independence.

Mr Aktar says the interpretation of the significance of the Battle of Gallipoli has shifted due to ideological reasons.

"Until 1950s, the historical narrative of Gallipoli was very secular. But then an Islamic narrative started to become dominant - that everybody who fought in Gallipoli fought for God and glory... But both these narratives are wrong."

There have been at least five Turkish feature films about the Battle of Gallipoli in recent years.

Serdar Akar, director of Gallipoli: End of the Road, says every Turkish filmmaker dreams of making a film on the subject.

"Every family in Turkey has a member who lost his life in the Battle of Gallipoli," he says.

Armenia: Rayhan Demytrie, BBC News Caucasus correspondent

Armenians are remembering their dead - but not those killed at Gallipoli

As subjects of Ottoman Turkey, ethnic Armenian soldiers fought and died in the Battle of Gallipoli. But people in the streets of the Armenian capital Yerevan know very little about it.

What they do know is that this year Turkey chose the date of 24 April to mark the anniversary of the battle, and that has not gone down well with most Armenians.

On this day for many decades, the Armenians have been commemorating the victims of what they call Meds Yeghern, or the "Great Catastrophe" - the mass extermination of ethnic Armenians in Ottoman Turkey.

This year is the 100th anniversary of the events, which many international scholars describe as "genocide".

The term "genocide" was first coined with the Armenian case in mind - an estimated 1.5 million died.

But Turkey does not agree and insists the number of Armenians killed was much less and that many died as a result of WW1.

Armenia's mass killings - explained in 60 seconds

Putting the historical dispute aside, Armenians feel that by marking the centenary of the Battle of Gallipoli on 24 April Turkey's intention has been to overshadow the Armenian commemorations.

Many here are waiting to see which world leaders will be heading to Turkey on Friday. They would rather see them coming to Yerevan to honour the memory of the Armenian men, women and children who perished in 1915-16.

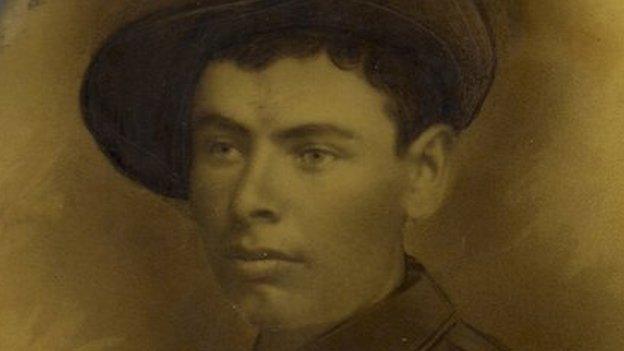

Northern Ireland: Julian Fowler, BBC News, Enniskillen

Irish soldiers at Gallipoli came from all backgrounds, Catholic and Protestant, fighting for King and British Empire.

In one day in 1915, 90 men from Enniskillen - part of the 1st Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers - were killed as they were led into a storm of machine gun and artillery fire.

Richard Bennett from the Inniskillings Museum on the contribution of Irish soldiers at Gallipoli

By December that year, only two officers and 114 men remained from the original battalion of 1,000 men which had landed at Gallipoli.

The area of the town where they lived became known as The Dardanelles, due to the large number of telegrams received by families informing them of their death.

The area was demolished in the 1960s and the name, along with their sacrifice, largely forgotten.

Richard Bennett from the Inniskillings Museum said after the Irish War of Independence - between 1919 and 1922 - the involvement of Irishmen fighting for the British Army "was something that people found reluctant to talk about".

It is only in the last 10 or 15 years that interest in the Irish experience in the Great War has revived. There has also been an acknowledgement that these men were volunteers as there was no conscription in Ireland.

Two Irishmen, Captain Gerald O'Sullivan from County Cork and Sergeant James Somers from County Cavan, were awarded the Victoria Cross as a result of their actions at Gallipoli.

They are being honoured by commemorative stones unveiled in Dublin to mark the centenary.

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that 35,000 British military personnel had died in the Gallipoli campaign, rather than 25,000.

- Published23 March 2015

- Published23 April 2015

- Published23 April 2015