Russian debtors despair as boom turns to bust

- Published

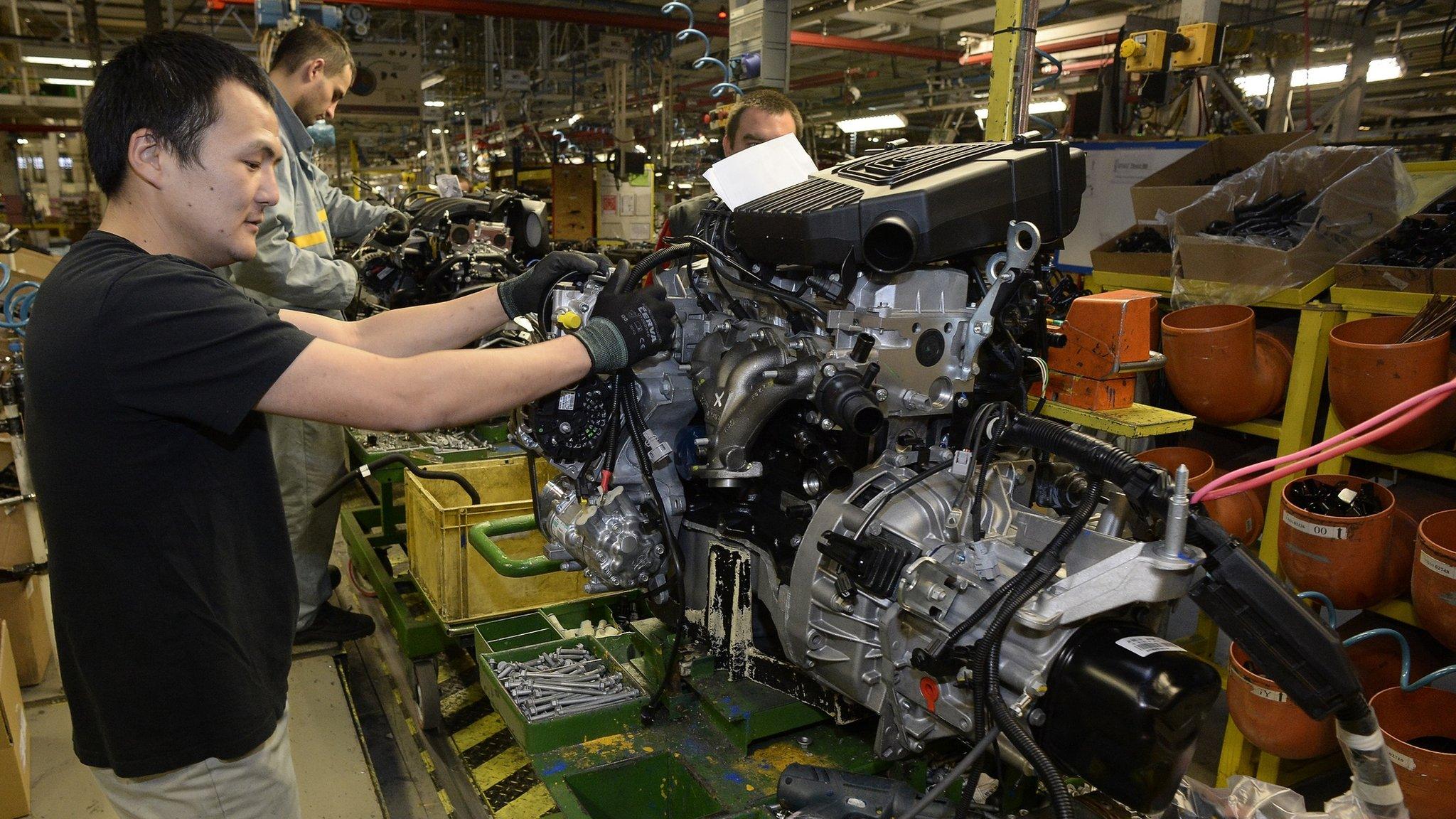

Credit offers tempted many Russian consumers after decades of hardship

Millions of Russians took out loans during the economic boom years, but now they face crippling debts and the law is not on their side, the BBC's Oleg Boldyrev reports.

At the start of each month Elena, a 40-year-old Muscovite, spreads all the family cash on the table and starts dividing it into small piles.

"When I do this I shake, I feel nauseous," she says.

"This goes to one bank, that to another, then the third one… There's one more bank, but we don't have the money for them - I had to go and buy some food. I guess we'll have to put up with their telephone reminders."

Elena and her husband owe well over 1m roubles (about £10,800; $17,000) to those four banks.

After the cash piles are sorted the family of three is left with only 10,000 roubles (£107; $167). That puts them below the poverty line - and recently Elena lost her job.

Debt mountain

Millions of those in debt live like Elena.

According to the Russian United Credit Bureau (UCB), 40 million Russians have loans or mortgages.

By June, 12.5m of those loans had not been paid for at least a month, and in another 8m cases the arrears stretched back over three months.

Shoppers in Moscow: Debts soared in the years before the 2008 financial crash

The Russian Central Bank says those chronic debts now total 1tn roubles (£10.7bn; $16.7bn). And that is at least 10% of the total personal debt - 10% which cannot be recovered by the banks.

For Elena and her husband, this is a story of almost two decades of borrowing. They started getting loans in the mid-1990s to pay for their daughter's medical treatment. Then they took a bigger loan to pay off the smaller ones.

It all seemed manageable, says Elena, but then new expenses came along - and two banks offered credit cards with generous conditions.

"We were a bit stupid," Elena says. "They told us the minimum payment was 5,000 roubles a month and we paid that every month. But that was just the interest, not the loan itself."

Sudden shocks

During Russia's boom years credit history checks meant virtually nothing. An individual already saddled with loans could take out another one, hoping to pay off previous debts. The small print was often too small to bother about.

Then the music stopped. Money got tight after the 2008 global financial crisis and Western sanctions against Russia over its role in the Ukraine conflict.

The average personal loan in 2014 was 54,600 roubles.

Olga Mazurova is head of Sentinel Credit Management, one of Russia's largest debt-collecting agencies. She says that often Russians are hit by a sudden drop in income, because "the firm goes bankrupt, the working week is cut, there are layoffs or wage cuts - we see that especially in industrial cities in Siberia and the Urals". Few Russians have insurance for such contingencies, she says.

Debtors cannot get much help. There are plans to amend the law on insolvency, to allow individuals to be declared bankrupt. But nothing will happen on that until October.

Russian MPs decided that criminal courts were unprepared for the likely flood of such cases and that courts of arbitration should handle debt cases instead.

Barvikha, Moscow: Luxury properties are still there for the small wealthy class

Each debtor has to beg the bank to cut them some slack. But Russia's financial ombudsman Pavel Medvedev says that rarely works if someone owes money to more than one institution.

A former adviser to President Vladimir Putin, he knows many top Russian financiers personally - but that does not help him to lobby on behalf of indebted callers. Typically, he says, lenders refuse to restructure personal debts with the words: "I've got a business to run and shareholders demand profits - I can't do it!"

Mr Medvedev says his success rate in helping debtors has dropped from 51% to 33% and "this year it's probably going to be around 16%".

No escape

He had no solution for one caller, Vladimir Frolov, living near Moscow.

Mr Frolov started borrowing four years ago to help his partner, living separately from him, in Ukraine. The debts snowballed. Finally, unable to get an unsecured loan, he mortgaged the flat he shares with his elderly parents.

His father Anatoly, who co-signed the agreement, is bewildered when asked which bank it was. "How should I know? They took us into some room, the light was dim and the print was tiny. I just asked if everything was alright and they told me it was."

Besides the mortgage, Vladimir Frolov's parents took out two loans to help him, which eat up 18,000 of their 22,000-rouble monthly pension allowance.

And now Vladimir has defaulted on the mortgage. The bank is suing and they may well lose their only dwelling.

"There must be a normal way out - maybe give the bank a fixed share of my wages?" Vladimir wonders. But so far he has not found anyone at the bank to discuss his dilemma.

"Isn't there a law against this?" asks his father, equally helplessly. "How can they let people borrow so much without checking them first?"

After the good years many Russians are now getting a harsh lesson in capitalism - and inadequate regulations mean there is nothing to soften the blow.

- Published13 April 2015

- Published25 March 2024

- Published15 May 2015